3.3 Different Energy Security concepts and dimensions

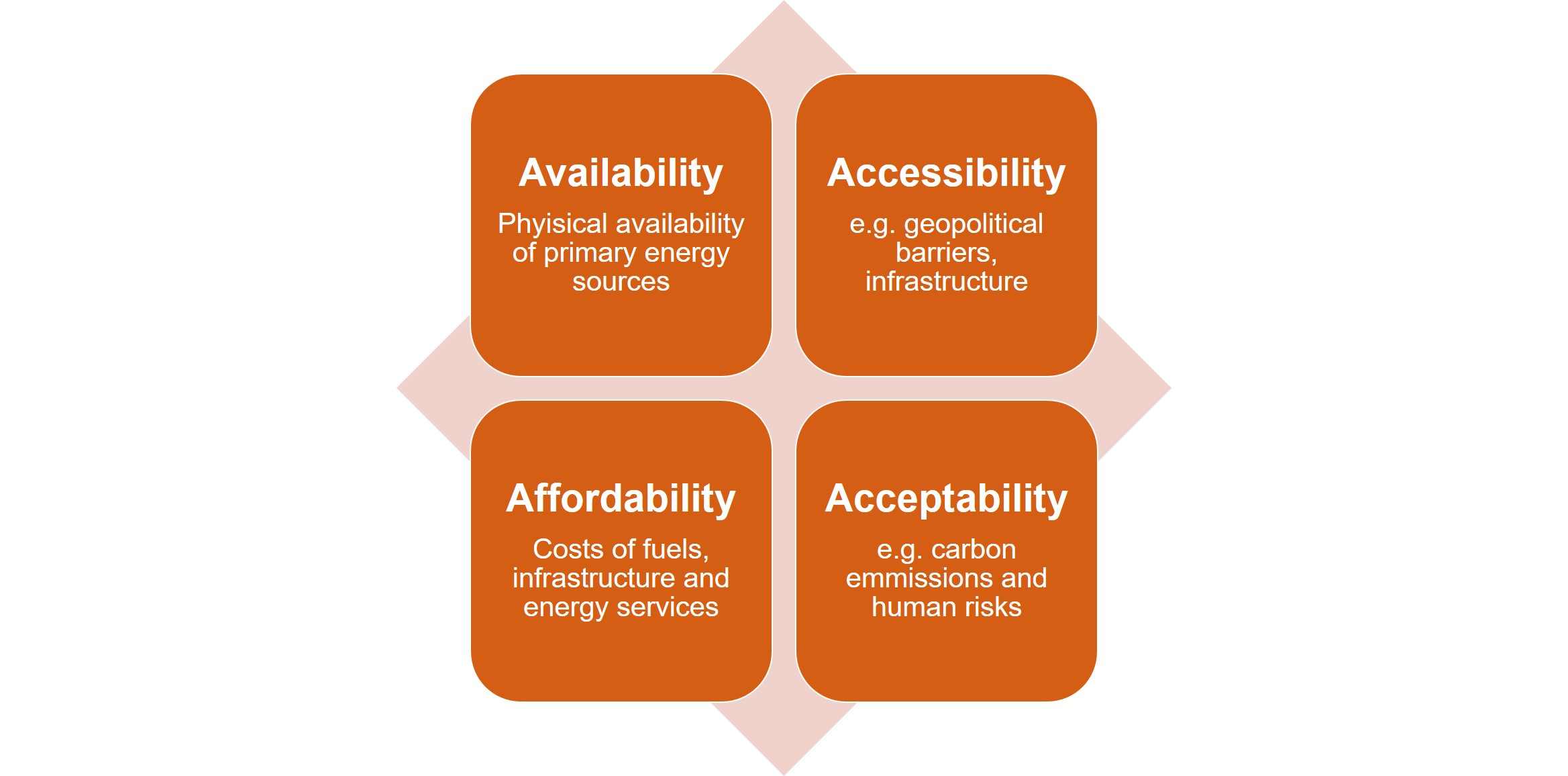

The 4 A´s

APERC 2007

The Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre (APERC) in 2007 introduced four dimensions (or 4 As) to assess energy security, focusing mainly on the energy supply security of national energy systems based on fossil fuels.

They can be described as follows:

-

Availability: It refers to the physical availability of primary energy sources including fossil fuels, radioactive matter, hydropower, biomass, wind and solar energy. The availability is high when the physical available primary energy is sufficient to meet demand.

-

Accessibility: Barriers to accessing energy resources like geopolitical factors, infrastructure, transport cost & distance, human resource capacity, financial subsidization, lack of commitment and limited access to advanced technology.

-

Affordability: With Affordability APERC (2007) refer to the capital cost of the infrastructure of different energy technologies. Further, fuel prices are mentioned, but not focused on.

-

Acceptability: According to APERC (2007), acceptability narrowly refers to the public perception of energy technologies regarding their contribution to climate change and their risk to cause environmental and nuclear hazards. In this sense, environmental policies to increase the environmental acceptability of the energy system add constraints on the use of as hazardous-perceived energy source (mainly oil, coal, and nuclear energy), and therefore, have a negative impact on energy security.

Why the “4 A’s” were criticized:

Criticism:

- Focus on conventional energy systems, underrepresenting the potential of renewable energy sources

- Focus on primary energy sources like coal and fuels

What is missing:

- Electricity related grid coverage and access

- Energy system resilience

- Potential of decentralized systems

- Social equity

The four A’s got widely cited, advanced, criticized and adapted to build a more holistic and multi-dimensional understanding of energy security. Main shortcomings/critics are the focus on a conventional, centralized energy system based on finite fossil fuels like natural gas, oil and coal as well as nuclear fuels (uranium) while underestimating the potential of renewable energy for contributing to energy security.

Furthermore, while environmental sustainability is stated as important objective in the introduction, it is not profoundly considered in the definition of the energy security dimensions. Additionally, social equity is not addressed in the definition of the dimensions.

Although the definition of the “4 As” by APERC (2007) has shortcomings, the unaddressed factors can be integrated within the “4 As”. The critics and advancements can be connected to the single dimensions as follows:

-

Availability: Decentralized renewable energy like solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal, tidal, and biogas and their potential for improving energy security energy security by e.g. decreasing import dependency, increasing primary energy supply diversity and lowering the negative impact on the environment shall be considered. In total the importance of a sustainable energy supply for long-term energy security is missing (Shah et al. 2019)

-

Accessibility: Economic factors within accessibility dimension interfere with capital cost infrastructure in affordability dimension (Hughes & Shupe, 2010).

-

Affordability: The affordability can have significant social and economic impacts (Hughes, 2012; Kruyt et al., 2009; Sovacool, 2011). Referring to social equity, Cherp and Jewell (2014) pose the question “affordable for whom?”

-

Acceptability: Sovacool (2011) and Hughes and Shupe add the themes of justice and equity, referring, for example, to the unjust displacements of indigenous people due to large energy projects.

The meaning of energy security is highly dependent on the national, regional or local context, e.g., physical conditions and barriers, level of economic development, perceptions of risks, as well as the robustness of its energy system and current geopolitical issues (Ang et al., 2015).

Furthermore, definitions and evaluations of energy security depend on the temporal and spatial scales (Pasqualetti & Sovacool, 2012) in focus.

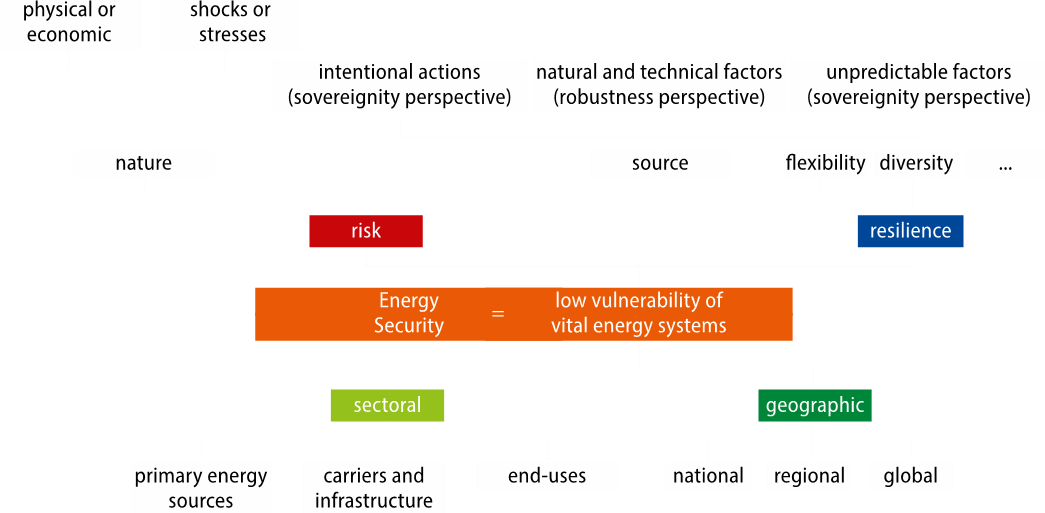

Cherp and Jewell, 2014: Vulnerability of energy supply systems as proxy for Energy Security

Cherp & Jewell 2014

In another approach, Cherp and Jewell (2014) go “beyond the four A’s” and define energy security as “low vulnerability of vital energy systems” (compare Figure). According to them, “vital energy systems are energy resources, infrastructure, and uses linked together by energy flows that support critical social functions which can be delineated by sectoral or geographic boundaries (e.g. ‘the Eurasian gas market’ or ‘the Western US electricity grid’).” In their framework, “vulnerabilities are combinations of exposure to risks and resilience capacities.”

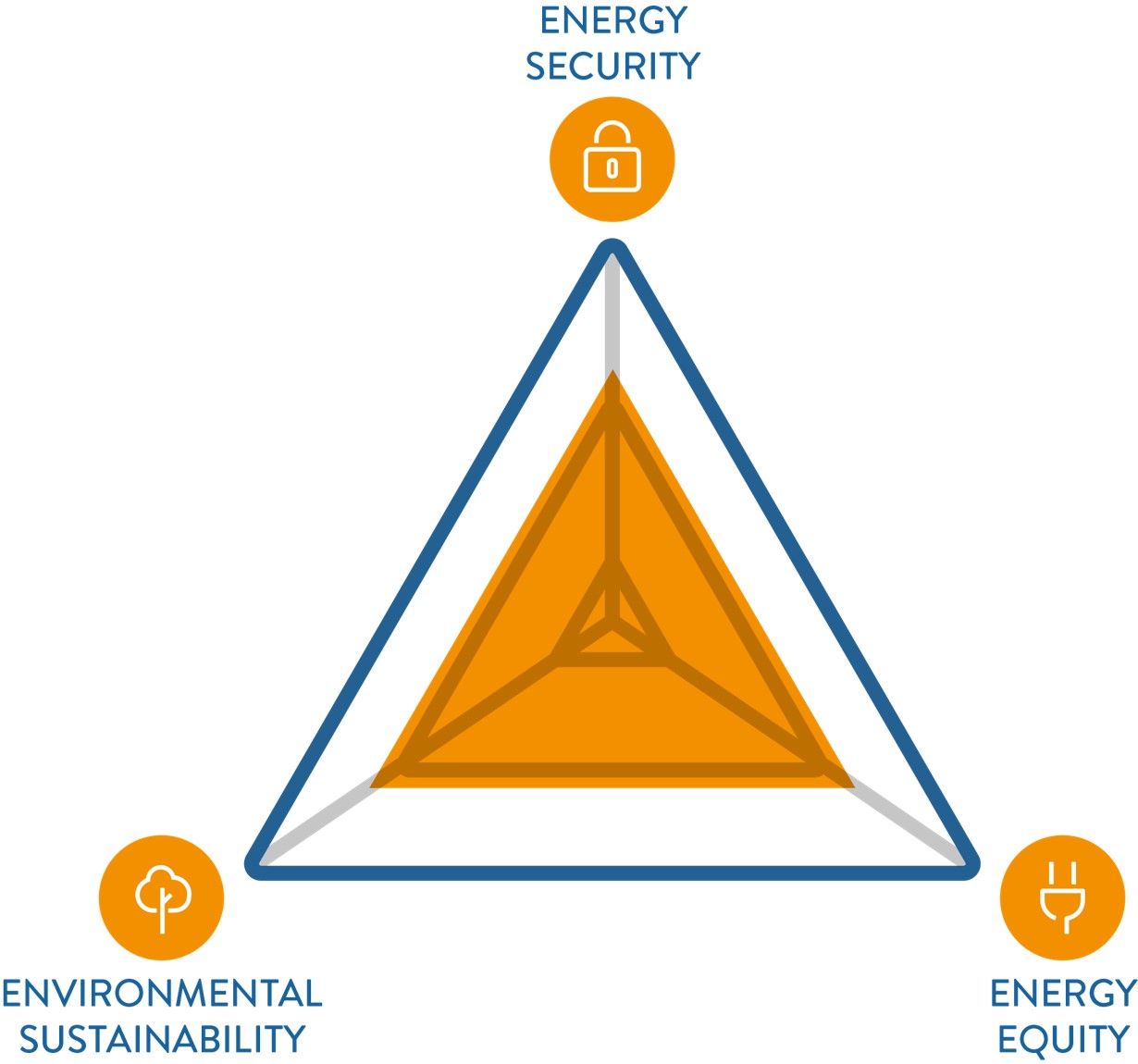

The World Energy Council (2020): The Energy Trilemma Index

World Energy Council 2020

The World Energy Council (2020) provides an alternative approach to evaluate and assess energy security. They state energy security, energy equity and environmental sustainability as the three dimensions of the “energy trilemma.” In there, they define energy security as “management of primary energy supply from domestic and external sources, reliability of energy infrastructure, ability to meet current and future demand”; energy equity as “accessibility and affordability of energy supply across the population”; and environmental sustainability as “reduction in energy and CO2 intensity, the transition to renewable and low-carbon energy sources”. Further, they underline that good energy governance manages the “competing demands” of the three dimensions and thus include the country context in the index.

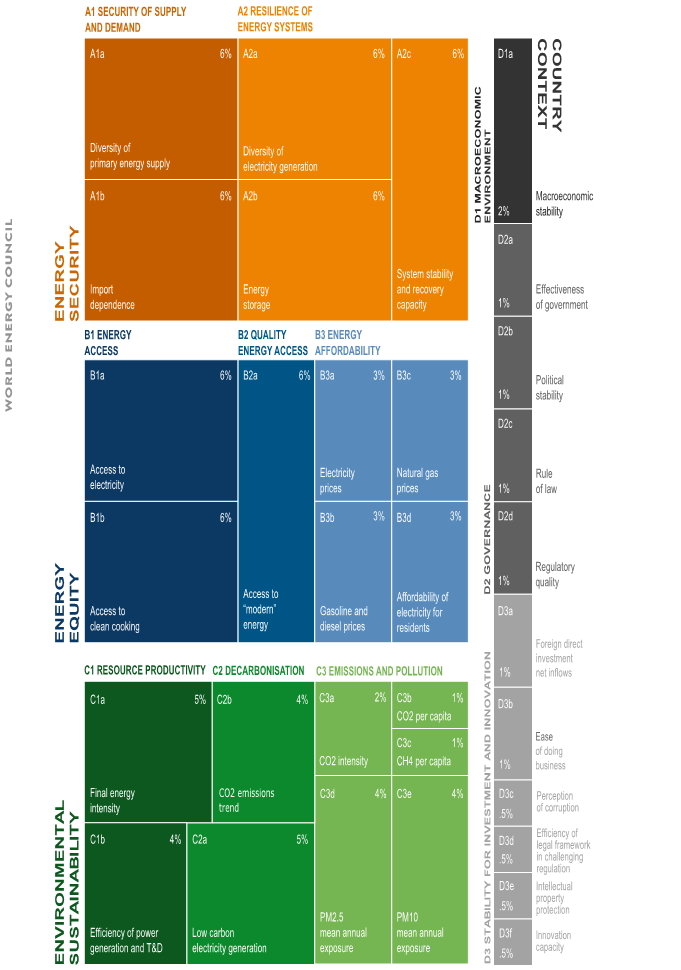

The Energy Trilemma Index: Subdimensions & Indicators

World Energy Council 2020

The dimensions of the Energy Trilemma Index, the subdimensions, as well as the used indicators including their weighting can be seen in the figure above and the corresponding report of the World Energy Council (2020). Energy security is subdivided into security of supply and demand, and resilience of energy systems.

Energy Equity consists out of the subdimensions energy access, quality of energy access, and energy affordability. Resource productivity, decarbonization, and emission and pollution form the dimension environmental sustainability. The country context is assed by indicators evaluating the macroeconomic environment, the governance, and the stability for investment and innovation. The full methodology and application example of the Energy Trilemma Index can be found in the inherent report.

Word Economic Forum (2016): Self-Sufficiency, Diversity of Supply and Accessibility to assess National Energy Security

World Economic Forum, 2016

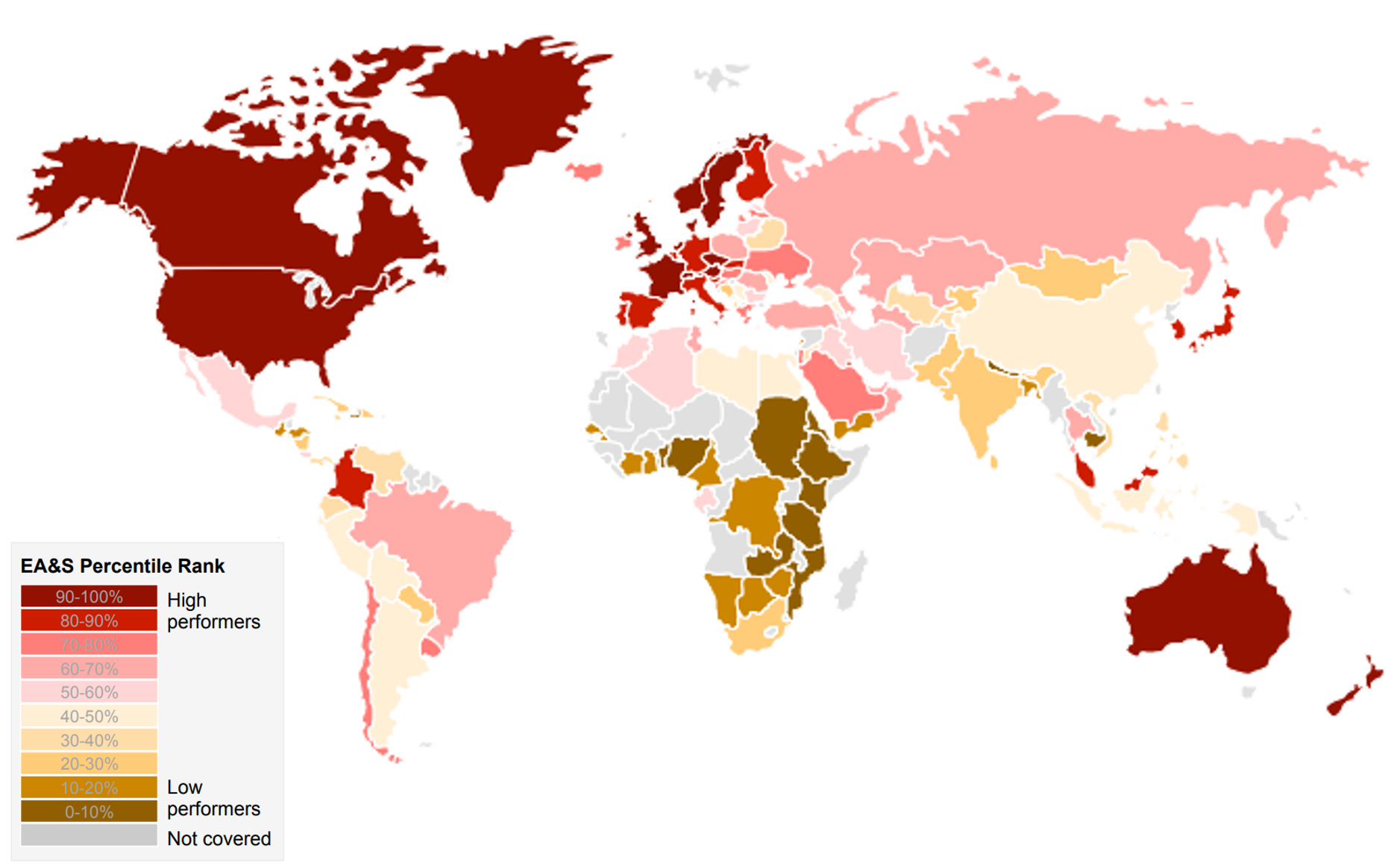

The World Economic Forum applied the Energy Access and Security Index to countries worldwide. They used the major dimensions:

- Self-sufficiency (diversification of import counterparts and energy imports)

- Diversity of supply (diversity of total primary energy supply)

- Level and quality of access (electrification rate, quality of electricity supply and population using solid fuels for cooking)

The high performing countries are located in Northern America, Western Europe, Australia and few countries in Asia. The worst performing countries are typically located in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the MENA and LAC regions, most countries are medium or poor performers, with Colombia, Chile, Uruguay and a several Gulf countries being an exception.

References

3.3 Different Energy Security concepts and dimensions

APERC, 2007. A Quest for Energy Security in the 21st Century: Resources and Constraints. https://aperc.or.jp/file/2010/9/26/APERC_2007_A_Quest_for_Energy_Security.pdf

Cherp, A., & Jewell, J., (2014). The concept of energy security: Beyond the four As. Energy Policy, 75, 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.09.005

Hughes, L., & Shupe, D., (2010). Creating energy security indexes with decision matrices and quantitative criteria. In World Energy Council’s 2010 Montreal Conference. http://dclh.electricalandcomputerengineering.dal.ca/enen/2010/ERG201002.pdf

Kruyt, B., van Vuuren, D. P., Vries, H.J.M. de, & Groenenberg, H. (2009). Indicators for energy security. Energy Policy, 37(6), 2166–2181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.02.006

Pasqualetti, M. J., & Sovacool, B. K. (2012). The importance of scale to energy security. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 9(3), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/1943815X.2012.691520

Shah, S.A.A., Zhou, P., Walasai, G. D., & Mohsin, M. (2019). Energy security and environmental sustainability index of South Asian countries: A composite index approach. Ecological Indicators, 106, 105507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105507

Sovacool, B. K. (2011). Evaluating energy security in the Asia pacific: Towards a more comprehensive approach. Energy Policy, 39(11), 7472–7479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.10.008

World Energy Council’s 2010 Montreal Conference. http://dclh.electricalandcomputerengineering.dal.ca/enen/2010/ERG201002.pdf

World Energy Council (2020): World Energy Trilemma Index. With assistance of Oliver Wyman Labs. Available online at https://trilemma.worldenergy.org/ (Tool).

World Economic Forum (WEF) (2016), ‘Global Energy Architecture Performance Index Report 2016’, Geneva. Available from: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Energy_Architecture_Performance_Index_2016.pdf