7.3.9 Constructed wetlands (CWs)

What are constructed wetlands?

A standard definition of wetlands comes from the Ramsar Convention (= Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat):

[Wetlands are] areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish, or salt including areas of marine water, the depth of which at low tide does not exceed 6 m.

Wetlands have unique hydrologic conditions and are ecotones (= a transition area between two biological communities) between terrestrial and aquatic systems. One of many wetland characteristics is standing water, unique soil conditions, and adapted organisms and vegetation to the saturated soils (Mitsch, 2013). In contrast to natural wetlands, CWs are engineered systems that use natural processes provided by vegetation, soils, and microbiological organisms to treat wastewater (Vymazal, 2010).

Types of CWs

From a technical point of view, Vymazal, 2010; Stefanakis, 2019; Maiga et al., 2017, classify CWs based on:

- hydrology (free water surface and subsurface flow) or

- vegetation type (emergent, submerged, floating leaved, free-floating) . Subsurface flow wetlands might be further divided based on their flow direction: vertical or horizontal flow CWs (Vymazal, 2010).

Application areas of CWs

-

Habitat creation

-

Flood control

-

Wastewater treatment

In this learning unit we focus on CWs for waterwater treatment. View contextual background

The majority of the global wastewater is not treated. Estimates suggest that industries and municipalities release 80% of untreated wastewaters into the environment every year (WWAP, 2017; Boretti & Rosa, 2019). The lack of wastewater collection, treatment and sanitation services is causing unacceptable hygienic, health, and environmental situations worldwide. In 2020, only 54% of the world’s population used safely managed sanitation services (UN Water, 2022). Therefore, incorporating solutions for wastewater treatment is vital to secure human and ecosystem health in the future and can also be done through a nexus approach.

Types of constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment (Maiga et al., 2017, adapted from Vymazal, 2008)

| Wetland Type | Free Water Surface Flow | Subsurface Flow |

| Type of Plants | Free-floating, floating-leafed, submerged, emergent | Emergent only |

| Direction of Flow | Horizontal | Horizontal or Vertical (vertical can be downflow or upflow) |

Benefits of CWs

- creation of new ecological habitats

- source of food and fiber

- stormwater management

- provides less costly and effective wastewater treatment

Challenges of CWs

- Higher evapotranspiration in hot and arid climates: Higher water losses via evapotranspiration in arid and hot climates can alter the water balance of CWs. As a result, salinity values might increase in a CW(Stefanakis, 2020).

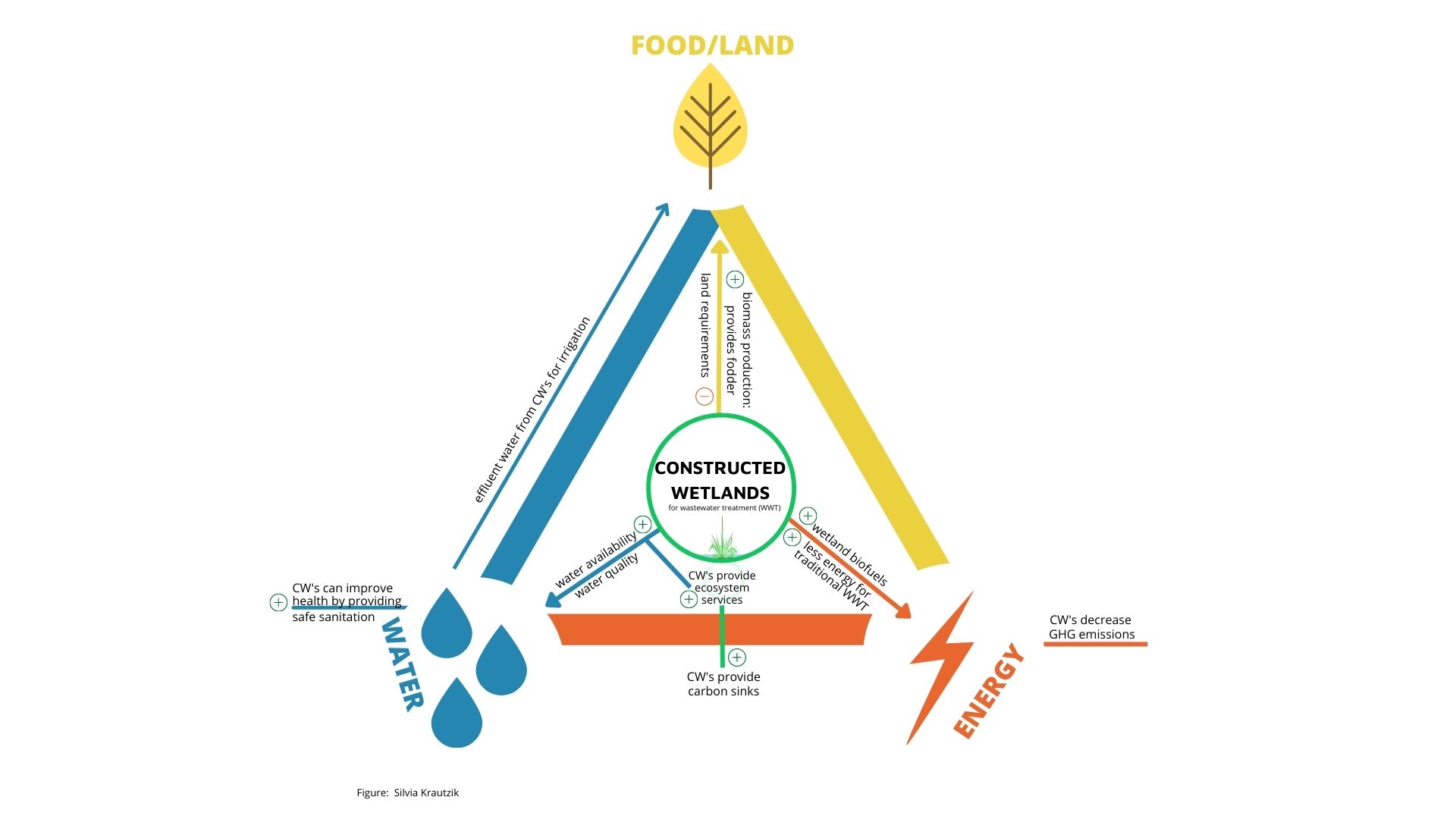

Constructed wetlands and its nexus connections

Source: "Linking wetlands to sectoral impacts", Silvia Krautzik.

Case studies

Example from an flower production company from Ethiopia near Lake Ziway

For instance, a flower production company from Ethiopia near Lake Ziway collects wastewater from four greenhouses and recycles it via constructed wetlands. The company operates 31 constructed wetlands and treats 500m³ of water per day (WWAP, 2017). The CWs purify wastewater streams, including fertilizer (nutrients), spraying water (with pesticides), bucket water, and cold storage water from the packhouses. The purification system can operate in the dry season with precipitation close to 0 mm and in the wet season with precipitation up to 145 mm/per month. However, since rainfall occurs in a few heavy events, some water will overflow or pass alongside the purification system. Another drawback is the Ethiopian electricity supply, which regularly fails and affects the purification systems timer, pumps, etc. Nevertheless, another challenge in the Ethiopian context is that construction materials and tools are not readily available and have to be imported. However, this is expensive and time-consuming (Van Dien & Bonne, 2015).

References

Boretti, A. & Rosa, L. (2019): Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report. In: Clean Water, 2(15), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-019-0039-9

Maiga, Y., von Sperling, M. and Mihelcic, J.R. (2017): Constructed Wetlands. In: J.B. Rose and B. Jiménez-Cisneros (eds), Water and Sanitation for the 21st Century: Health and Microbiological Aspects of Excreta and Wastewater Management (Global Water Pathogen Project). (J.R. Mihelcic and M.E. Verbyla (eds), Part 4: Management Of Risk from Excreta and Wastewater - Section: Sanitation System Technologies, Pathogen Reduction in Sewered System Technologies), Michigan State University, E. Lansing, MI, UNESCO. https://doi.org/10.14321/waterpathogens.66

Mitsch, W. J. (2013): Wetland Creation and Restoration. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 367–383. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-384719-5.00221-5

Stefanakis, A. I. (2020): Constructed Wetlands for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment in Hot and Arid Climates: Opportunities, Challenges and Case Studies in the Middle East. Water, 12(6), 1665. doi:10.3390/w1206166

UN WATER (2022): Progress on Sanitation (SDG target 6.2). Available at: https://sdg6data.org/indicator/6.2.1a#:~:text=SDG%20target%206.2%20is%3A%20’By,and%20those%20in%20vulnerable%20situations.&text=1a%20monitors%20the%20proportion%20of%20population%20using%20safely%20managed%20sanitation%20services [Accessed: 01.03.2022].

VAN DIEN, F.& BOONE, P. (2015): Evaluation Report. Constructed Wetlands Pilot at Sher Ethiopia PLC.

Vymazal, J. (2010): Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. Water, 2(3), 530–549. doi:10.3390/w2030530

WWAP (United Nations World Water Assessment Programme) (2017): The United Nations World Water Development Report 2017. Wastewater: The Untapped Resource. Paris, UNESCO.