7.3.4 Agroforestry Systems

Overview: What is Agroforestry?

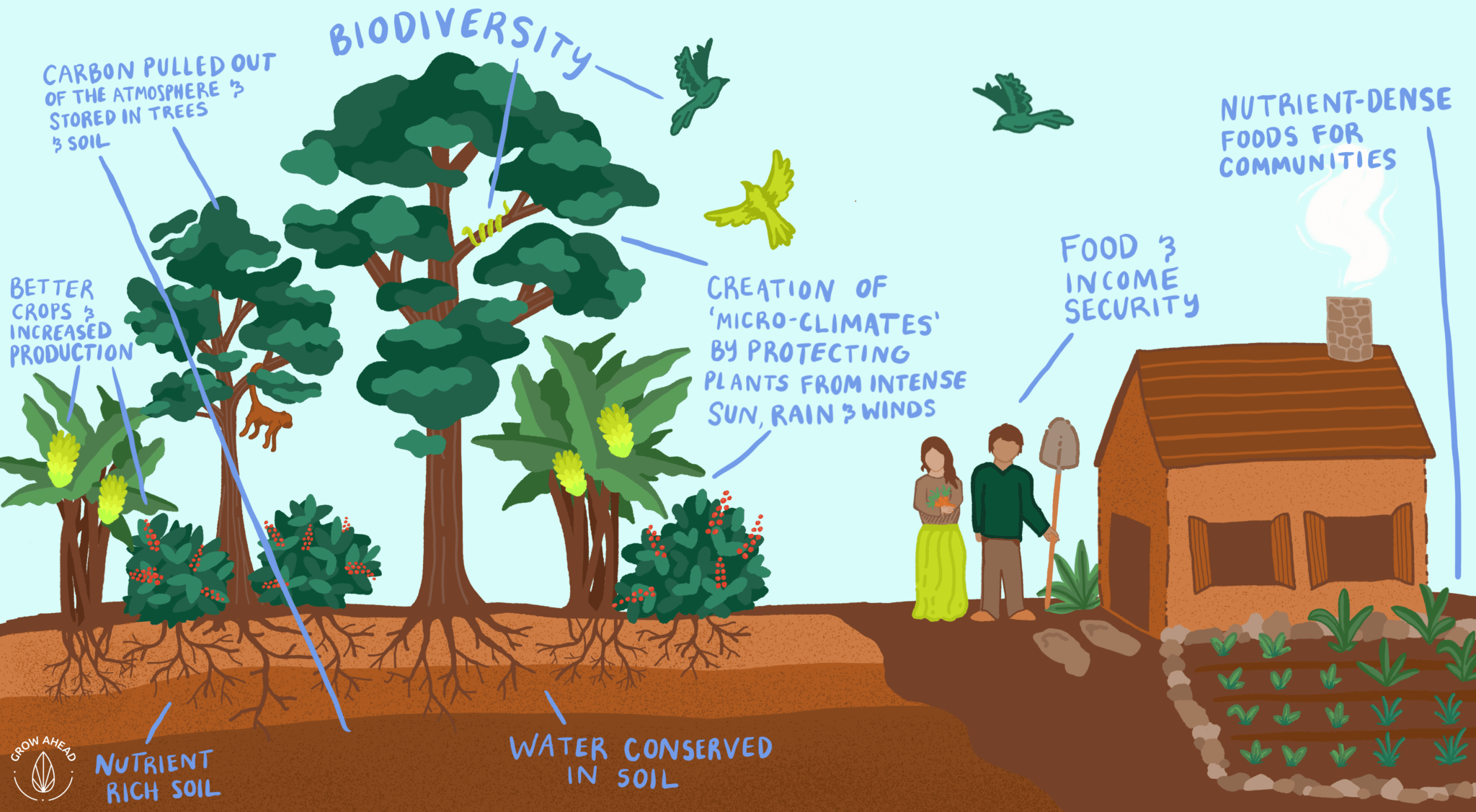

Image from Growahead, available at https://growahead.org/plant-trees/

Image from Growahead, available at https://growahead.org/plant-trees/

Agroforestry is the combination of woody perennials (e.g., trees, shrubs, palms, bamboos) with crops and/or animals (Wilson & Lovell, 2016) that diversifies and sustains production for increased social, economic, and environmental benefits for land users at all levels (FAO, 2015).

The term agroforestry describes the multi-use of an area of land for woody perennials (trees, palms, bamboo..) and agricultural crops or animals. By some definitions, agroforestry means having at least 10% of the area need to be covered with trees (Zomer et al. 2014). Agroforestry is practiced in order to diversify a farmers production and ideally increase the total yield, thus providing higher food security. At the same time it can provide benefits to soil fertility, carbon sequestration, water regulation and resilience to hazards (FAO and ICRAF 2019; Castle et al. 2021).

As such, agroforestry systems have been recommended by the UN and the FAO. In total, more than $US 10 billion have been mobilized for agroforestry projects since the 1992 Earth Summits in Rio (Castle et al. 2021).

All in all, agroforestry is not a new technique, in some sort of way it is a ‘new name for an old practice’. It originated as a means to preserve tropical rainforests. The acknowledgement of the importance of tropical forests, and the need for conservation through agroforestry practices increased the importance for the research, political, and financial support in the 20th century and beyond (Atangana 2014). According to Zomer et al. (2014), in 2014 around 50% agricultural land in developing country regions was intercropped with trees.

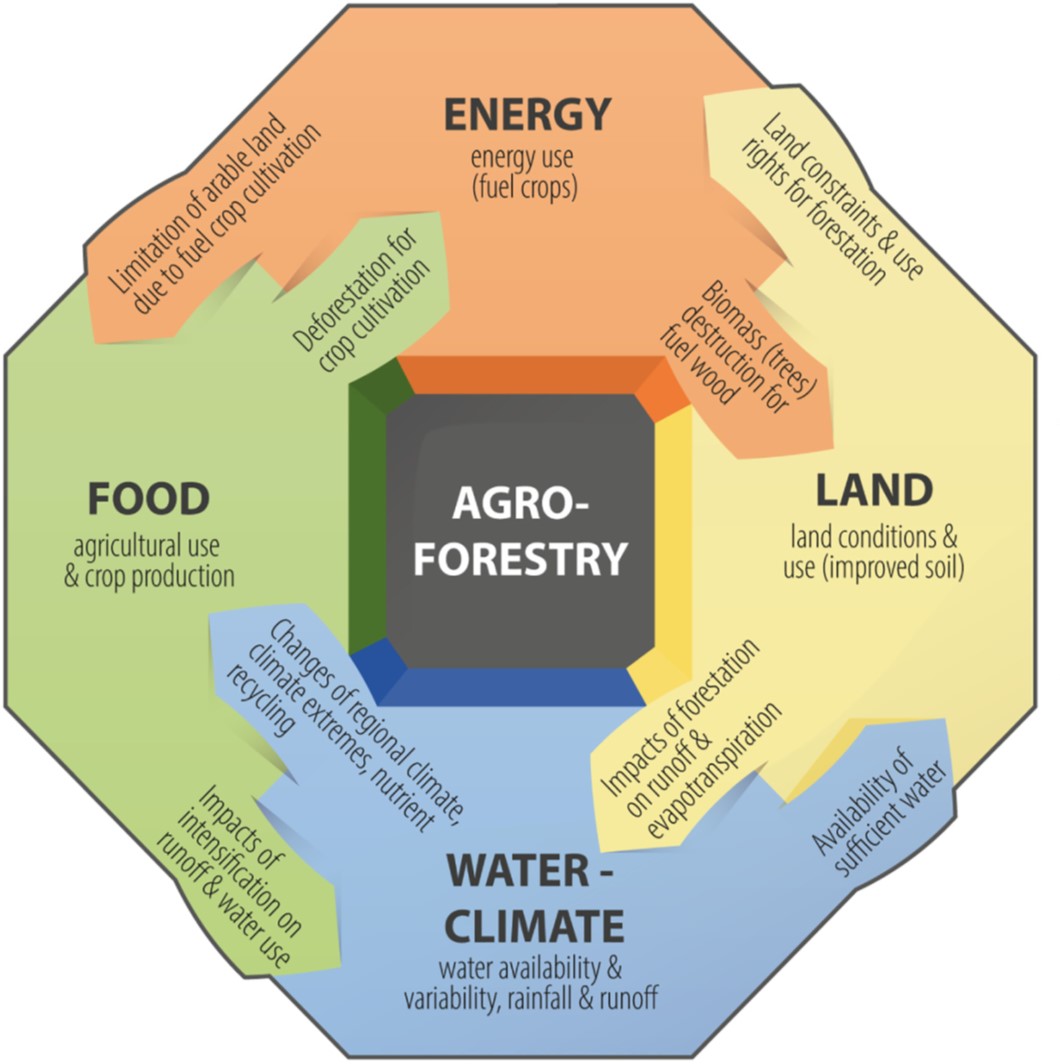

Impacts of agroforestry on the Water Energy Land Food (WELF) Nexus

Source: Elagib and Al-Saidi (2020)

Source: Elagib and Al-Saidi (2020)

When looking at the Nexus, it can be seen that there are potential effects on all aspects. A case study by Elagib and Al-Saidi (2020) highlights the impacts of agroforestry on the Water Energy Land Food (WELF) Nexus.

Starting from the land conditions, AF systems can decrease runoff and evapotranspiration, increasing the water availability. Availabilty of water in turn can help to keep good land conditions stable. The dual use of land could also reduce land competitions, as fuel wood and crops are grown within the same area, albeit agroforestry allows for less trees per square meter than conventional forestry. AF does therefore not serve to completely dissolve the issue, tradeoffs still have to be accounted.

Agroforestry systems also allow for a more favourable micro-climate, which can allow for increased growth of crops. Resilience increases both through diversification and through improved soil condidtions (Elagib and Al-Saidi, 2020).

Agroforestry System (FoFo SAF)

Productivity The plants of the FoFo SAF are collocated considering their syntropy potential, cost, yield, and market price. The average yield and market prices are estimations based on secondary data and empirical knowledge from the local producers of Acre.

Quantification of economic benefits The revenues were calculated based on the assumption that the farmers have full market access and that their whole production can always be sold. Net present value is calculated for a project duration over 20 years and at a discount rate of 8.25%. The Final Net Present Value of the FoFo agroforestry system prototype sums up to 182 234 R$ (around 30 000 € in 2021) with a payback period of 4 years.

The Net Present Value is sensitive to the discount rate (≙weighted cost of capital), plant configuration, yields, and market prices. Interviewed agroforestry farmers confirmed increased quantity and resilience in income, aside from improved work conditions, health, cooperation, knowledge gain, and identification with the land and ecosystem. Given the results, the authors expect additional income, biodiversity, and resilience gains through the application of FoFo SAF.

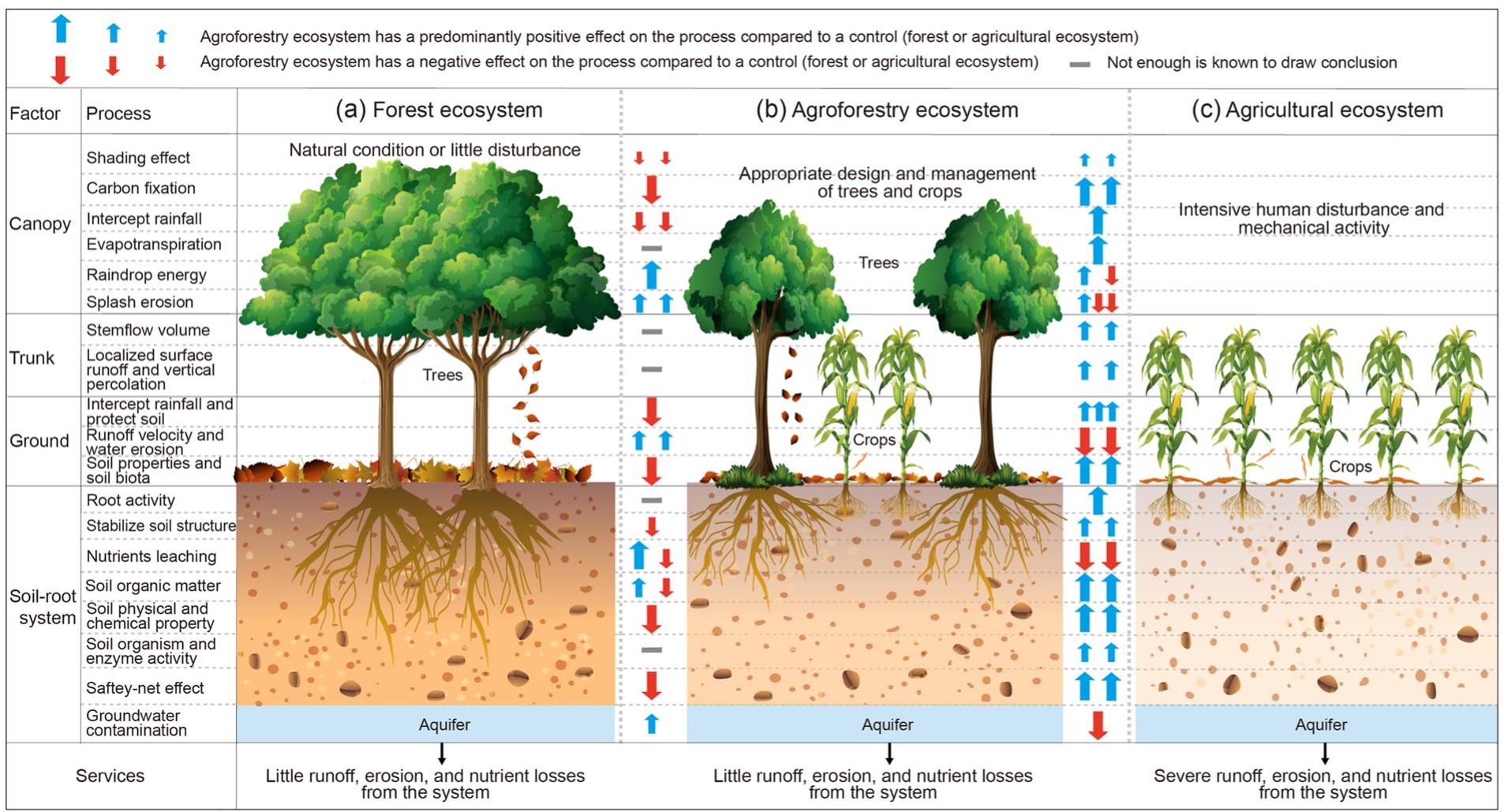

Benefits of Agroforestry compared to agricultural systems

Source: Zhu et al. 2020

Source: Zhu et al. 2020

WEFE benefits

Agroforestry is multifunctional and can provide various economic, sociocultural, and environmental benefits (FAO, 2015). Within the Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystem (WEFE) Nexus, benefits include food production, reduction in nutrient and pesticide runoff, carbon sequestration, increased soil quality, erosion control, improved wildlife habitat, increased resilience to extreme events, and lowering the fossil fuel use and overall energy demand of agricultural production (Platis et al., 2019; Wilson & Lovell, 2016). Conducting an evidence-based synthesis, Zhu et al. (2020) found that agroforestry systems reduce surface runoff, soil erosion, and related organic carbon and nutrient losses on average by 58%, 65%, 9%, and 50%, respectively. Moreover, they found that agroforestry systems lower the impact of herbicides, pesticides, and other pollutants on water resources by 49% on average.

Geographic Context

According to FAO (2015), agroforestry can be especially beneficial to smallholder farmers in rural areas due to its potential to enhance food supply, income, and health. Besides, companies are establishing large-scale agroecological systems (Pentagrama, 2021). The efficiency of agroforestry systems is strongly site-dependent and varies widely depending on different biophysical factors like climate, soil type, ecology, and sociocultural and economic settings. Therefore, agroforestry systems’ type and design must be adapted to hydrometeorological, ecological, sociocultural, and economic site conditions (Zhu et al., 2020).

Variants

Five main agroforestry practices can be identified (U.S. Department of Agriculture; Wilson & Lovell, 2016):

-

Alley Cropping refers to the combination of tree or shrub alleys and agricultural or horticultural crops. The alleys control wind erosion, provide shade, increases infiltration, protect crops, and improve crop yield and wildlife habitat.

-

Silvopasture: Combination of pasture grazing and forestry for phytoremediation, minimizing soil nutrient loss, and the production of fodder, fruit, livestock, and shade (Zhu et al., 2020)

-

Riparian Buffers: Natural or re-established streamside forests made up of tree, shrub, and grass plantings. They can reduce runoff and nonpoint source pollution, control soil erosion and nutrient loading, and improve internal drainage, and enhance infiltration

-

Windbreaks: strips of hardwood trees and shrubs enclosing fields and pastures. They can control wind erosion, protect crops and livestock, and improve crop yield and wildlife habitat (Zhu et al., 2020).

-

Forest Farming: Cultivation of high-value crops, like mushrooms and medicinal herbs, under the protection of a managed, established forest canopy using the vertical space and the microclimate of the forest.

Impacts of agroforestry

Sources: Zhu et al. 2020.

Conducting an evidence-based synthesis, Zhu et al. (2020) found that agroforestry systems reduce surface runoff, soil erosion, and related organic carbon and nutrient losses on average by 58%, 65%, 9%, and 50%, respectively. Moreover, they found that agroforestry systems lower the impact of herbicides, pesticides, and other pollutants on water resources by 49% on average.

As can be seen in the illustration however, there was a wide range of observed effects, with negative impacts also being observed. The efficiency of agroforestry systems is strongly site-dependent and varies widely depending on different biophysical factors like climate, soil type, ecology, and sociocultural and economic settings. Therefore, agroforestry systems’ type and design must be adapted to hydrometeorological, ecological, sociocultural, and economic site conditions (Zhu et al., 2020).

These findings are supported by Castle et al. (2021). The authors of the review study investigated the impacts of agroforestry interventions on agricultural productivity, ecosystem services and human well being in low- and middle-income countries.They found that in total, there is a large positive effect on agricultural yield, the variations however are also large. The authors conclude that agroforestry interventions “may lead to positive food security outcomes” and higher income for small scale farmers, but the effects are highly dependent on local circumstances (Castle et al. 2021).

Agroforestry and its theory of change

AF: Agroforestry. Illustration from Miller et al. (2020).

A study by Miller etal. (2020) developed a theory of change for successful agroforestry interventions. The ideal system provides positive final outcomes on all the examined aspects of agricultural productivity, ecosystem services and human well-being. It highlights the importance of proper crop selection adopted to the local circumstances and education in the first steps (Miller et al. 2020).

If the prerequisites are fullfilled, the implementation of agroforestry projects leads to improved soil and water management, increasesd tree-cover and a multi-functional tree porfolio. All of these cause improved soil health and quality and increased revenues from the diverse products. Furthermore, additional products like firewood can be used on-site, to decrease household expenses on the farm. The improved soil quality leads to higher yields or to lower costs for the same amount of production. The increased yield, as well as the diverse production leads to greater financial security and diverse sources of food. This in turn allows for the final outcome of increased human well-being, beneficiary ecosytem services and increased agricultural production.

Despite the opportunities, agroforestry systems still face some challenges such as vague land use rights, inadequate capacities and lack of investments. (Elagib and Al-Saidi 2020)

Furthermore, in research, insecure land and resource tenure is often mentioned as a main challenge. It has been shown that the likelihood of farmers adopting and reaping benefits from agroforestry increases with long term and secure tenure. “This is because farmers require longer time periods to test, adapt and eventually adopt agroforestry technologies and practices, due to the often lengthy periods required for trees to mature” (FAO and ICRAF 2019)

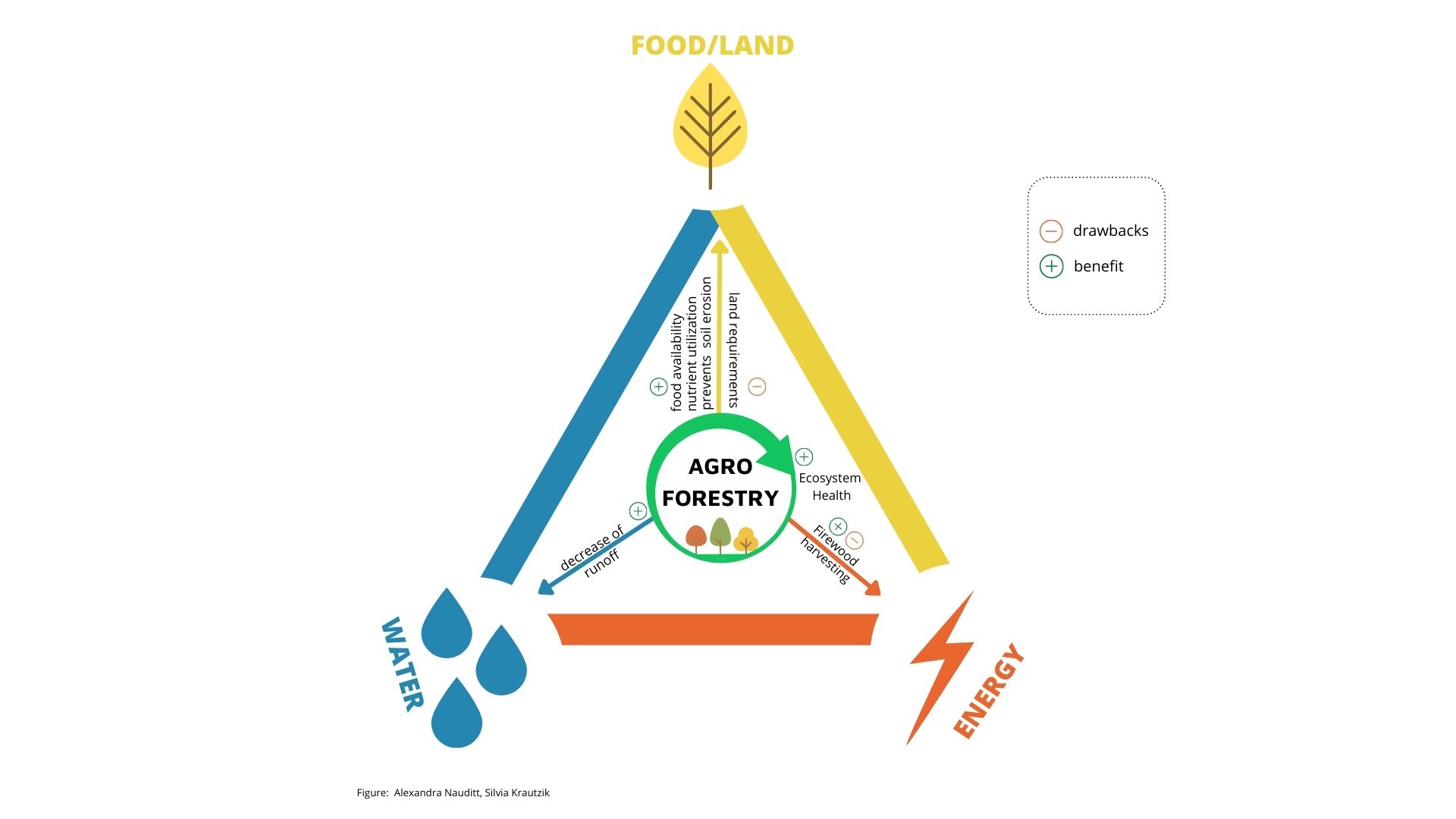

Integrating Agroforestry into nexus systems - an overview

The figure below highlights key interconnections between agroforestry systems and WEF-systems.

“Integrating Agroforestry into WEF-Systems”. Source: Alexandra Nauditt, Silvia Krautzik

“Integrating Agroforestry into WEF-Systems”. Source: Alexandra Nauditt, Silvia Krautzik

Next solution: RE Desalination

References

Overview: What is Agroforestry?

FAO. (2015). Agroforestry: definition. http://www.fao.org/forestry/agroforestry/80338/en/

FAO; ICRAF (2019): Agroforestry and tenure. Foresty working paper no. 8. Rome.

Castle, Sarah E.; Miller, Daniel C.; Ordonez, Pablo J.; Baylis, Kathy; Hughes, Karl (2021): The impacts of agroforestry interventions on agricultural productivity, ecosystem services, and human well‐being in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic review. In Campbell Systematic Reviews 17 (2), e12740. DOI: 10.1002/cl2.1167

Wilson, M., & Lovell, S. (2016). Agroforestry—the next step in sustainable and resilient agriculture. Sustainability, 8(6), 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8060574

Zomer, R. J.; Trabucco, A.; Coe, R.; Place, F.; van Noordwijk, M.; Xu, J. (2014): Trees on farms: An update and reanalysis of agroforestry’s global extent and socio‐ecological characteristics. Edited by World Agroforestry Center.

Impacts of agroforestry on the Water Energy Land Food (WELF) Nexus

Elagib, N.A. and Al-Saidi, M. (2020): Balancing the benefits from the water-energy-land-food nexus through agroforestry in the Sahel. In The Science of the total environment 742, p. 140509. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140509

Agroforestry System (FoFo SAF)

Todeschini de Quadros, B. (2017). Prototyping agroforestry systems with unconventional food plants (PANC): an innovative approaxch to sustainable food production systems for smallholders in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. KU Leuven.

Benefits of Agroforestry compared to agricultural systems

FAO. (2015). Agroforestry: definition. http://www.fao.org/forestry/agroforestry/80338/en/

Pentagrama. (2021). Large-scale agroforestry systems. https://www.pentagramaprojetos.com.br/en/large-scale-agroforestry-systems

Platis, D., Anagnostopoulos, C., Tsaboula, A., Menexes, G., Kalburtji, K., & Mamolos, A. (2019). Energy analysis, and carbon and water footprint for environmentally friendly farming practices in agroecosystems and agroforestry. Sustainability, 11(6), 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061664

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Agroforestry practices. https://www.fs.usda.gov/nac/practices/index.shtml

Zhu, X., Liu, W., Chen, J., Bruijnzeel, L. A., Mao, Z., Yang, X., Cardinael, R., Meng, F.-R., Sidle, R. C., Seitz, S., Nair, V. D., Nanko, K., Zou, X., Chen, C., & Jiang, X. J. (2020). Reductions in water, soil and nutrient losses and pesticide pollution in agroforestry practices: A review of evidence and processes. Plant and Soil, 453(1-2), 45–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04377-3

Impacts of agroforestry

Castle, Sarah E.; Miller, Daniel C.; Ordonez, Pablo J.; Baylis, Kathy; Hughes, Karl (2021): The impacts of agroforestry interventions on agricultural productivity, ecosystem services, and human well‐being in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic review. In Campbell Systematic Reviews 17 (2), e12740. DOI: 10.1002/cl2.1167.

Zhu, X., Liu, W., Chen, J., Bruijnzeel, L. A., Mao, Z., Yang, X., Cardinael, R., Meng, F.-R., Sidle, R. C., Seitz, S., Nair, V. D., Nanko, K., Zou, X., Chen, C., & Jiang, X. J. (2020). Reductions in water, soil and nutrient losses and pesticide pollution in agroforestry practices: A review of evidence and processes. Plant and Soil, 453(1-2), 45–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04377-3

Agroforestry and its theory of change

Miller, D. C., Ordoñez, P. J., Brown, S. E., Forrest, S., Nava, N. J., Hughes, K., & Baylis, K. (2020). The impacts of agroforestry on agricultural productivity, ecosystem services, and human well‐being in low‐and middle‐income countries: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16, e1066.

FAO; ICRAF (2019): Agroforestry and tenure. Foresty working paper no. 8. Rome.