7.3.6 Wind Desalination for Irrigation

Description, Geographic Context, & Variants

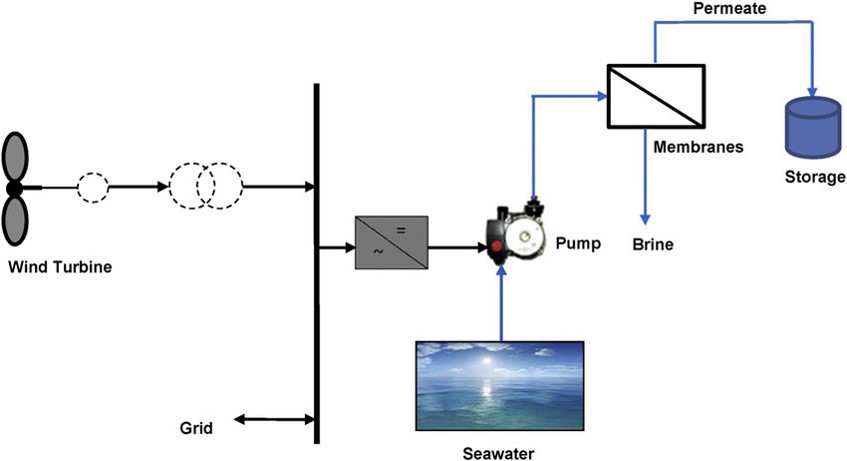

Schematic wind desalination system (Gökçek & Gökçek, 2016)

Schematic wind desalination system (Gökçek & Gökçek, 2016)

Wind-powered reverse osmosis desalination presents an attractive water-energy-food nexus sound solution combing the sustainability of renewable energy and the maturity of reverse osmosis with irrigation for food crops (Fornarelli et al., 2018).

Wind turbines convert wind energy into electrical energy. The electricity powers the high pressure pump of the reverse osmosis unit. The pressure lets pure water permeate across the membranes, leaving behind water of high salt concentration (brine). The desalted water is pumped to storage or reservoir. Although various efficiency gains could be reached in reverse osmosis, it remains a very energy-intensive technology and following the water-energy nexus also water-intensive technology.

Further, the management of brine (Giwa et al., 2017) is crucial to avoid negative impacts on the local environment. Due to these shortcomings, other available water sources on-site (rainwater, dew, wastewater, river, lake, groundwater) should be considered in the decision-making process.

WEFE Interconnections

The connection between renewable energy and water treatment taps various synergies within the nexus of water, energy, food, and climate. Thereby, wind power plants boast the lowest life-cycle CO2-emission (IPCC Working Group III, 2014) and energy-related water demand (Okadera et al., 2014) among all energy production technologies. Water treatment units can act as a deferrable load allowing demand-side management to increase the uptake of fluctuating wind energy resources.

The water reservoir is a strategic buffer storing desalted water when irrigation is not needed and providing it in times of water scarcity and/or high water demands (Serrano-Tovar et al., 2019). Moreover, the reservoir could also be used as pumped hydropower providing energy storage capacity to buffer the fluctuations in wind energy availability.

Geographic Context

Seawater desalination addresses the challenge of water scarcity and seawater intrusion in coastal areas. Given renewable energy potentials, on-site, solar, wind, or hybrid power plants can be economically viable and environmentally preferable options to power desalination.

Good locations for onshore wind turbines feature high, continuous wind speeds confirmed by professional wind speed measurements, low surface roughness, high air density, stable ground, and well-developed transport infrastructure. Environmental and public regulations must be considered in the planning process, e. g. the site should not be inside of a nature reserve and be at a certain distance to residential areas. For on-grid systems, the grid electricity price should be higher than the levelized cost of electricity of the wind turbine to ensure economic viability.

Wind turbines connected to the grid benefit from the low life cycle CO2 emissions, and, especially in areas of high wind speeds, low levelized cost of electricity from wind turbines. In off-grid settings, like in remote islands and areas with access to sea- or brackish water, wind energy has additional advantages over fossil-fuel-based energy systems due to its decentral availability.

Variants

Wind desalination systems are part of the group of renewable-energy-powered water treatment and distribution systems. For small-scale applications, there is a high market potential for solar-thermal membrane distillation systems and solar and/or wind electrodialysis for low salinity water resources (IRENA, 2015).

Depending on the water source and quality and the aimed end-use, water treatment technologies can do various services besides desalination like disinfection, removal of minerals, chemicals, and organic compounds. The water sources range from surface water, groundwater, collected rainwater to wastewater. Further, solar and wind resources can also drive water pumps, e.g., for irrigation, similarly tapping synergies by using water tanks as indirect energy storage (Poompavai & Kowsalya, 2019).

Case Study Wind Desalination for Irrigation (1): Site Conditions

Aerial View Wind Desalination for IrrigationSystems, standard north up representation

Source: Serrano-Tovar et al. (2019) applying visor of IDECanarias (2015)

Overall Setting

The private company Soslaires Canarias S.L. operates a wind-powered desalination system using reverse osmosis close to Playa de Vargas, at the east coast of Gran Canaria (27.890137, -15.394638). The operators sell the water for irrigational purposes to farmers of a local agricultural cooperative cultivating fruits and vegetables. Data and information regarding the case study are retrieved from Serrano-Tovar et al. (2019).

Biophysical Site Conditions

The climate in subtropical Gran Canaria is under the influence of the Azores anticyclone, the trade winds, and the Atlantic Ocean, leading to mild winters and warm summers with rather small temperature differences between the seasons, and especially in the South and East of the island to aridity. Average high temperatures range between 21°C in January and 26°C in August, while average low-temperature range between 14°C in January and 21°C in August. Overall annual precipitation in 2019 at Playa de Vargas summed up to 85.0 mm (Gelaro et al., 2017). The average wind speed in 2019 was 8.49 m⁄s and the average air density was 1.196 kg⁄m^3 (Gelaro et al., 2017).

WEF challenges, tradeoffs, and demands

Gran Canaria faces various challenges related to physical water scarcity and growing water demand. Population growth and extensive tourism development have led to a high increase in water and energy demand on the island. Traditionally used insular aquifers could not meet the demand and are depleting. The open space in the aquifers has led, especially in the Southeast of the island, to seawater intrusion. Further, the porosity of the volcanic rocks in Gran Canaria challenges the storage of water in reservoirs. To cope with water scarcity and high water demand, the Gran Canaria strongly relies on desalination. Around 51 % of the island’s water demand for human consumption is met through desalination, accounting for 7% of the island’s energy demand (de la Fuente, 2018)

Case Study Wind Desalination for Irrigation (2): Technologies, Components and Performance

System Components & Performance

The Wind Park consists of four Vesta V47 660 wind turbines providing an overall power capacity of 2.64 MWp. The overall surface area of the wind park is 8800 m². The annual production capacity of the Reverse Osmosis Unit is 1.8 Mm³ with an average specific energy consumption of 4.2 kWh/m³. The reverse osmosis and pumping system occupy a surface area of 450 m². The water desalted water is stored in a 9500 m² reservoir with a capacity of 200,000 m³, located at 200m above sea level. The specific electricity consumption for water pumping is 1.1 kWh/m³. The desalted water irrigates up to 282 ha of agricultural land of a local famers’ association. Various fruits and vegetables are cultivated in the fields.

Synergies tapped/Efficiency Gains

The case study boasts typical synergies identified for combining renewable energy and desalination (section 1). Tangibly. The water reservoir acts as a strategic buffer storing desalted water when irrigation is not needed and providing it in times of water scarcity and high water demands. Furthermore, the electricity grid is used as an additional strategic buffer, taking up excess electricity at times of high wind power production and providing electricity in days of low wind power production and high water demand.

Case Study Wind Desalination for Irrigation (3): Yield and Cost

Yield

The electricity production of the wind turbines (4*Vesta V47 660) for the location of Playa de Vargas can be estimated using renewables.ninja (Staffell & Pfenninger, 2016) based on MERRA-2 data. The yield of wind turbines is often expressed in capacity factors, i.e., “the ratio of the average load carried by a power station or system for a given period to the rated capacity of the station or system for the same period” (Merriam-Webster). While daily maxima can be observed in March and November, July and August boast a constantly high production, resulting in the highest monthly capacity factors (65.14 % and 66.83 %, respectively).

The total annual electricity production is estimated to be 10.40 MWh in 2019, corresponding to a mean capacity factor of 0.45 and 3942 full load hours (FLH). The measured annual electricity production in 2015 is 9.28 MWh, corresponding to a mean capacity factor of 40% and 3504 FLH. The capacity factor is extraordinarily high, indicating very good conditions for wind energy development.

Cost

Given the case study data (Serrano-Tovar et al., 2019), assuming constant electricity and water yields over a project lifetime of 20 years and a discount rate of 7%, the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) calculates as 4.83 €_cents/kWh and the levelized water cost as 1.48 €/m³.

For comparison: Literature values for levelized cost of electricity from wind turbines in Germany ranges from 3,.99 €_cents/kWh to 8.23 €_cents/kWh . Literature values for levelized cost of water for wind-driven reverse osmosis systems range from 1.8 to 3.4 USD⁄m^3 (IRENA, 2015). LCOE and LWC mainly depend on the full load hours and the weighted average cost of capital, i.e., the discount rate (IRENA 2015). The relatively low levelized cost for electricity and water can be explained by the high amount of full load hours of the deployed wind turbine obtained thanks to the excellent conditions for wind energy deployment at the east coast of Gran Canaria.

Next solution: Water and Electricity Cogeneration

References

de la Fuente, Juan Antonio. (2018). The Canary Islands experience: current non-conventional water resources and future perspectives. ITC Canarias, Gobierno de Canarias. https://www.gwp.org/contentassets/aa500f6c8cb749d7ac324a4065395386/203.the-canary-islands-experience.pdf

Fornarelli, R., Shahnia, F., Anda, M., Bahri, P. A., & Ho, G. (2018). Selecting an economically suitable and sustainable solution for a renewable energy-powered water desalination system: A rural australian case study. Desalination, 435(10), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.11.008

Gelaro, R., McCarty, W., Suárez, M. J., Todling, R., Molod, A., Takacs, L., Randles, C. A., Darmenov, A., Bosilovich, M. G., Reichle, R., Wargan, K., Coy, L., Cullather, R., Draper, C., Akella, S., Buchard, V., Conaty, A., da Silva, A. M., Gu, W., . . . Zhao, B. (2017). The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (merra-2). Journal of Climate, 30(14), 5419–5454. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1

Giwa, A., Dufour, V., Al Marzooqi, F., Al Kaabi, M., & Hasan, S. W. (2017). Brine management methods: Recent innovations and current status. Desalination, 407, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2016.12.008

Gökçek, M., & Gökçek, Ö. B. (2016). Technical and economic evaluation of freshwater production from a wind-powered small-scale seawater reverse osmosis system (wp-swro). Desalination, 381(2), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2015.12.004

IDECanarias. (2015). Sistema de información territorial de canarias. https://visor.grafcan.es/visorweb/

Kost, C., Shammugam, S., Jülch, V., Nguyen, H.-T., & Schlegl, T. (March 2018). Levelized Cost of Electricity: Renewable Energy Technologies. Fraunhofer ISE. https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/en/documents/publications/studies/EN2018_Fraunhofer-ISE_LCOE_Renewable_Energy_Technologies.pdf

(2014). Mitigation of Climate Change: Technology-specific cost and performance parameters. Table A.III.2 (Emissions of selected electricity supply technologies (gC02eq/kWh). IPCC Working Group III. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_annex-iii.pdf#page=7

Merriam-Webster. Capacity factor: definition. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/capacity factor

(2015). Renewable Energy in the Water, Energy and Food Nexus. IRENA. https://www.irena.org/publications/2015/Jan/Renewable-Energy-in-the-Water-Energy–Food-Nexus

Okadera, T., Chontanawat, J., & Gheewala, S. H. (2014). Water footprint for energy production and supply in thailand. Energy, 77(4), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.03.113

Poompavai, T., & Kowsalya, M. (2019). Control and energy management strategies applied for solar photovoltaic and wind energy fed water pumping system: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 107, 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.02.023

Serrano-Tovar, T., Peñate Suárez, B., Musicki, A., La Fuente Bencomo, J. A. de, Cabello, V., & Giampietro, M. (2019). Structuring an integrated water-energy-food nexus assessment of a local wind energy desalination system for irrigation. The Science of the Total Environment, 689, 945–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.422

Staffell, I., & Pfenninger, S. (2016). Using bias-corrected reanalysis to simulate current and future wind power output. Energy, 114, 1224–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.08.068