7.3.1 Integration of Photovoltaics and Agriculture: Agrivoltaics

Agrivoltaics: generating electricity while saving water – increasing WEF resources productivity

PV magazine; Antoine Bolcato

Agriphotovoltaics (APV): Improving Water, Energy and Food Supply

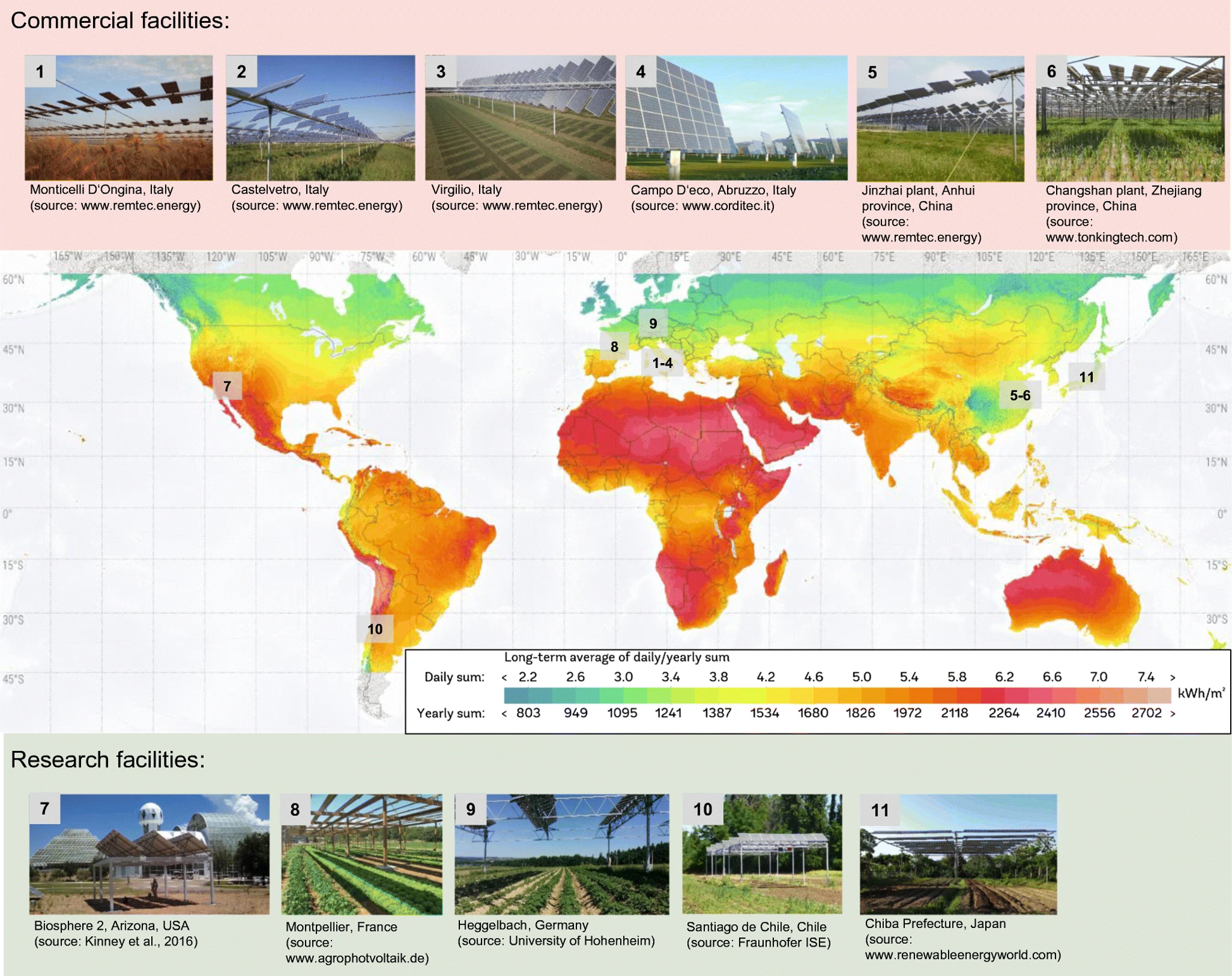

Agrivoltaics have various synergistic effects linked to shading through the solar panels and the microclimatic effects of introducing plants: The shading reduces evaporation from the soil and transpiration from crop canopy, increasing soil moisture and irrigation water-use efficiency (Hassanpour Adeh et al., 2018).

Further, especially in hot, dry, and sunny climates, shading can prevent depression in photosynthesis through heat and light stress allowing greater plant growth (Barron-Gafford et al., 2019; Trommsdorff et al., 2021). Finally, the crops provide transpirational cooling to the photovoltaic panels, increasing their efficiency (Adeh et al., 2019).

Overview of APV projects and facilities with location. The color gradient indicates the long-term average of daily/yearly sum of global horizontal radiation [kwh/m2]. The numbers indicate the location of the described facilities (Global horizontal irradiation map © 2018 The World Bank, Solar resource data: http://solargis.com/, used under CC BY 3.0 IGO, modified from original)

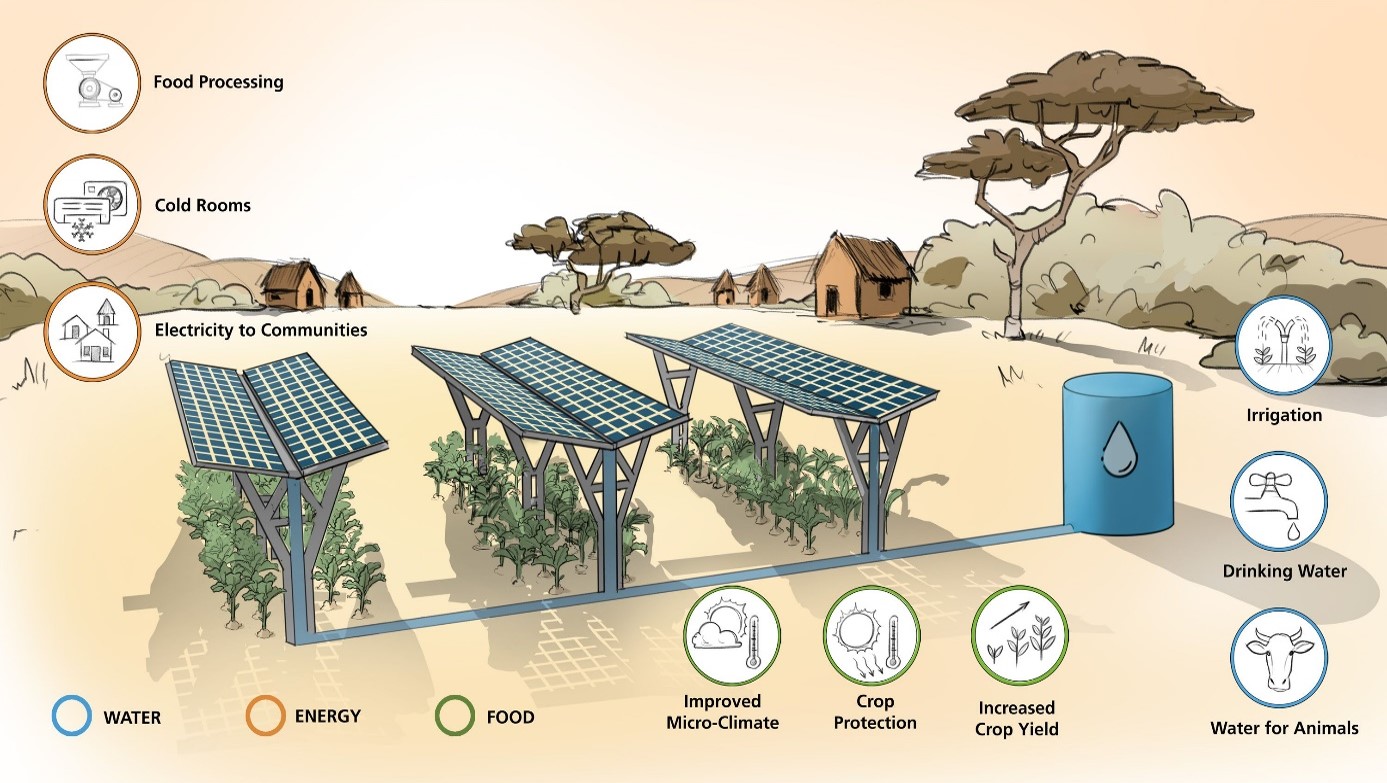

Agrivoltaics: how to use the increased WEF productivity

Fraunhofer ISE

Agrivoltaics integrate photovoltaic panels in agricultural systems. The setup allows multiple land-use of agricultural areas by adding electricity production through solar panels and optionally rainwater harvesting from the panel surfaces (Fraunhofer ISE) as productive uses. The produced electricity can be used for food processing and energy supply of local communities or be fed into the national grid (given suitable remuneration schemes).

Agrivoltaics have various synergistic effects linked to shading through the solar panels and the microclimatic effects of introducing plants: The shading reduces evaporation from the soil and transpiration from crop canopy, increasing soil moisture and irrigation water-use efficiency (Adeh et al., 2018). Further, especially in hot, dry, and sunny climates, shading can prevent depression in photosynthesis through heat and light stress allowing greater plant growth (Barron-Gafford et al., 2019; Trommsdorff et al., 2021). Finally, the crops provide transpirational cooling to the photovoltaic panels, increasing their efficiency (Adeh et al., 2019).

Benefits

-

No competition for land resources One central issue with renewable energy systems is the competition for agrarian land. Wind turbines require a lot of space, ground-mounted solar PV is mostly used in flat and sunny areas that could be used for agriculture. Additionally, a variety of crops are grown solely for energetic use: in Germany, 14% of the agricultural area is used for bioenergy (Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe 2020). As both the demand for food and energy is projected to increase (IRENA 2018; FAO 2017) , the conflict for land resources can be expected to grow.

One approach to reduce land competition is the use of Agrivoltaics (AVP). The technology describes the use of photovoltaic systems above cropland, harvesting both solar energy and agricultural products, thus reducing land competition. In general, the dual use of land can affect the efficiency of both systems, but allows for a higher total land use efficiency, as illustrated in the graphic. -

Shadowing effects on crops

Images from: 1) Fraunhofer ISE (2020) and 2) Sinovoltaics.com

While the total efficiency of the PV systems may decrease, the dual use of land can actually lead to an increase in yield of crops. The effect on the total yield depends mainly on the insolation, the crop and the soil, as well as the rate of shadowing of the APV construction. In general, plants do not utilize incoming light, once a certain threshold is reached. This means that after a certain point, photosynthesis stops and additional sunlight will not serve to further grow a plant and can even be harmful. (Runkle 2015) Especially in arid climate, it has been shown that yields can increase substantially due to additional shadowing.

Most APV systems are built on an axis that supports solar tracking, so the insolation could be adjusted to the needs of the crops in different stages, through turning the solar modules.

For most crops, moderate shading, meaning reducing the insolation by 20-30%, gives better results than severe shading (>= 50%). (Weselek et al. 2019; Touil et al. 2021)

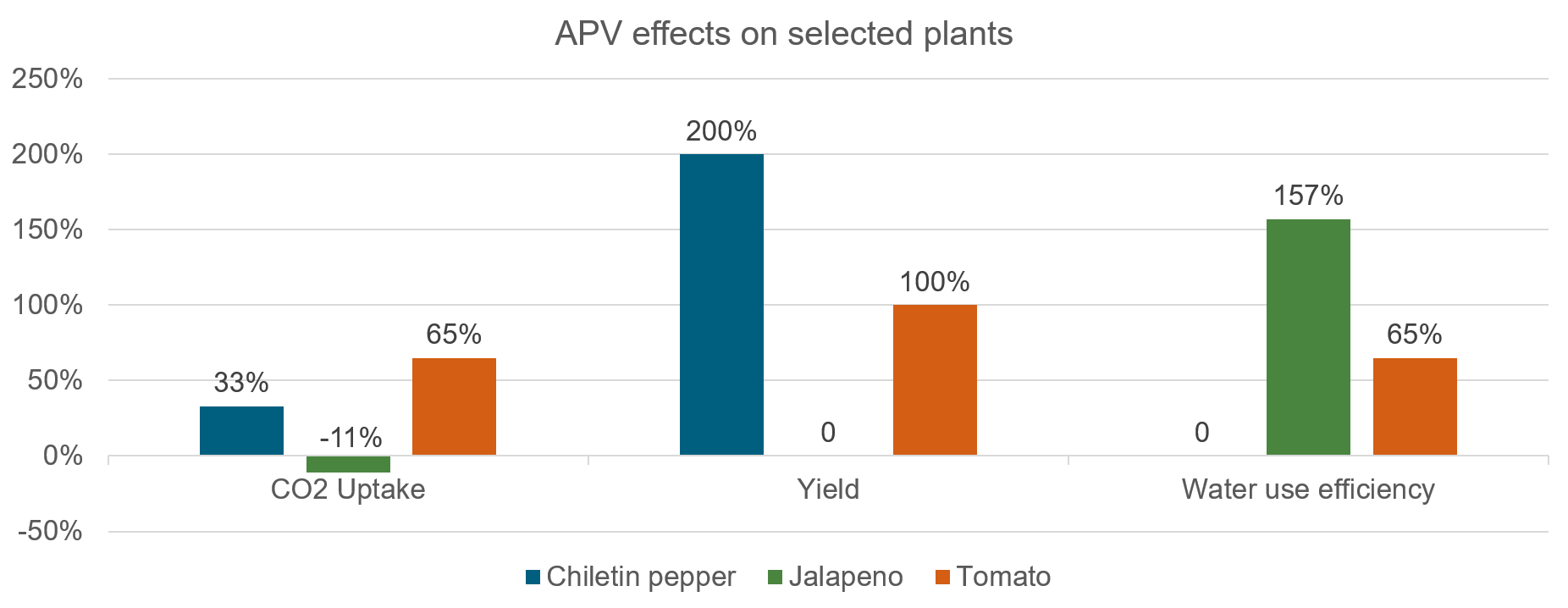

- Impacts on generation, crop yield and water efficiency

Graph adapted from Barron-Gafford et al. (2019)

Graph adapted from Barron-Gafford et al. (2019)

Using synergetic effects to (ideally)

- Generate electricity

- Decrease water consumption

- Increase crop yield

A control study by Barron-Gafford (2019) et al. showed that the effects of an AVP are either nil or very positive for the growth of selected crops. For the Chiletin pepper, the yield tripled, for the tomatoes it doubled. Furthermore, the water use efficiency improved significantly for Jalapenos and Tomatoes and stayed the same for the Chiletin pepper (Barron-Gafford et al. 2019).

The soil moisture beneath the AVP system remained around 15% greater in the APV field in comparison to the control field, suggesting a higher resilience for dry periods. (Barron-Gafford et al. 2019). According to the Fraunhofer Institute (2020), through APV the need for irrigation can be reduced by up to 20% (Fraunhofer ISE 2020).

Review papers by Weselek et al. (2019) and Touil et al. (2021) support these findings. They also report some cases however, where decreasing yields of up to minus 50% were observed. It is therefore crucial to assess both the climate and the crops. Shade tolerant plants like leafy vegetables (lettuce, spinach) and root crops (potatoes, radishes, beets, carrots) (Adeh et al., 2019), as well as special crops like berries, wild garlic, asparagus, and hops, appear as particularly suitable to collocate with photovoltaic panels (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020). In theory, APV provides even more synergetic effects.

If the system is designed that way, occurring precipitation can be collected from the modules and saved for later use. (Fraunhofer ISE 2020) In addition, the efficiency of PV systems decreases with increasing surface temperature. The evapotranspiration and the latent heat of the vegetation below APV modules, can help to cool them off. The study by Barron-Gafford et. al (2019) found that in their case, the temperature of the panels decreased by around 9°C during the growing season, resulting in a 3% increase in electricity generation (Barron-Gafford et al. 2019).

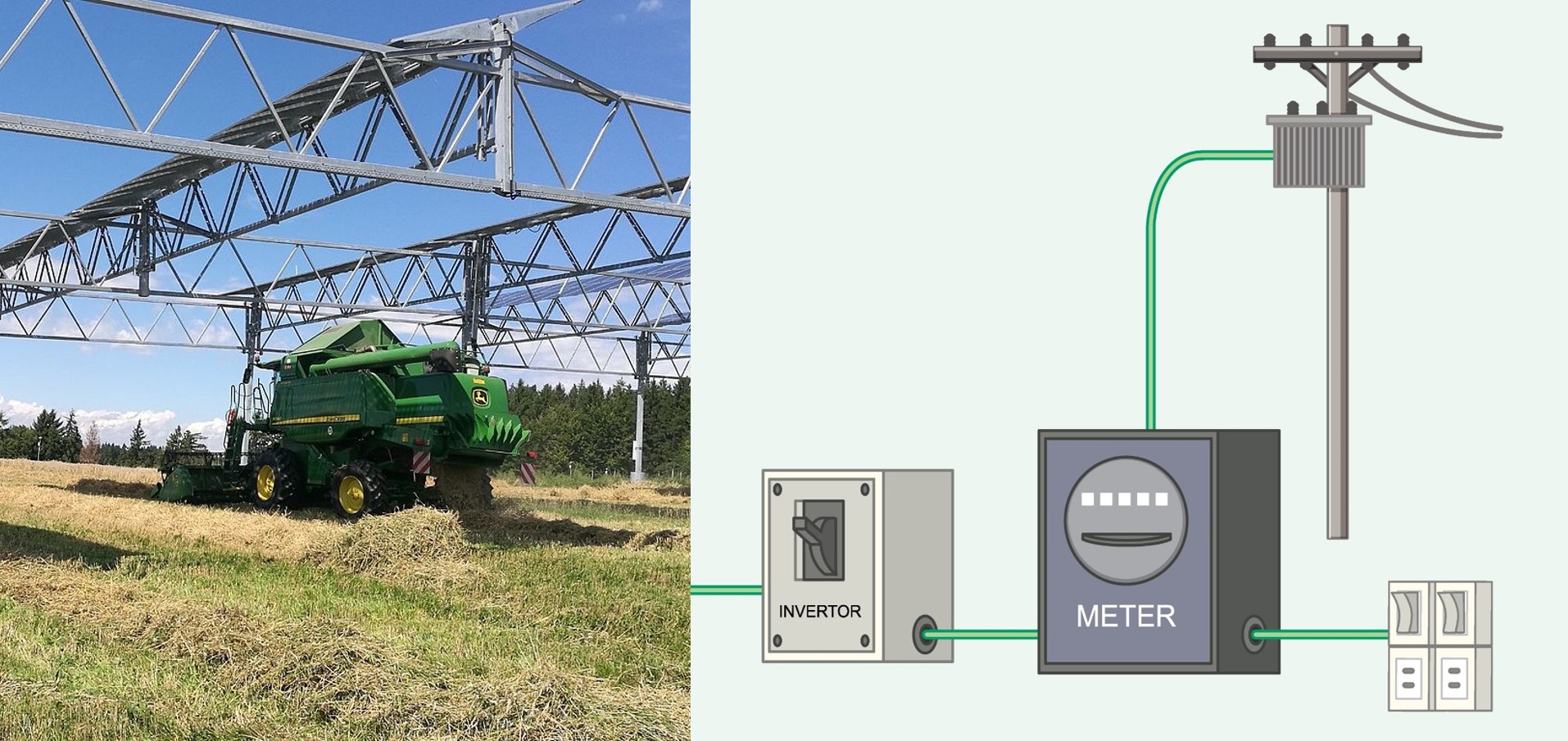

Agrivoltaic system and components

Images from (1) M. Thrommsdorf at Wikimedia commons (2) brgfx at freepik.com

Components An APV system consists of the standard PV components:

- The PV modules, where electricity is generated. Photovoltaic cells within the photovoltaic panel convert the sunlight’s energy to electric energy using the photovoltaic effect.

- An inverter, that converts the generated direct current (DC) into alternating current (AC). Alternating current is widely used to power most of our devices. However, many devices (light bulbs, USB-charger, refrigerator, TV) exist as DC versions. Thus, inverters and their conversion losses can be omitted by fully relying on DC devices.

- A meter, that measures the generated electricity.

- A connection either to the grid or to a battery storage. If a battery is present, a charge controller is needed and the inverter is installed behind the battery.

- A controll panel with fuses for security

An APV system also comprises:

- The mounting structure, including either no, a single or a dual axis for tracking

- A water management system if desired. (Fraunhofer ISE 2020)

Sizing System sizes range from few kW peak and m² systems for the local supply (see case study in next sections) to large scale grid-connected projects with food production for regional, national and global markets (e.g., 1GWpeak on 107 m^2 Goji-Berry Agrivoltaic System near to Gobi desert in China (Bellini, 2020).

In Agrivoltaics systems featuring plants that do not require big machinery for cultivation and are of rather low height(e.g., berries, wine), the clearance height of the mounting structure can be reduced. As a result, lower material demand leads to overall lower construction costs and lower levelized cost of electricity (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020).

In these special cultivation practices, protection from sunburn, hail, and strong winds and the integration with existing protection and cultivation structures (e.g., hop, wine) plead for agrivoltaic cropping systems. Performance

Electrical Efficiency The electrical output depends on the overall surface of all the photovoltaic panels installed, the incoming solar radiation, the efficiency of the panels & the inverters, the cleanliness of the panels, and the ambient temperature.

Plant Growth Plant growth and yield depend strongly on the availability of light. Optimum levels of photosynthesis are reached at the light saturation point, while lower and higher radiation levels lead to a decrease in photosynthesis (Chapin et al., 2011). Further limiting factors of plant growth are temperature and water availability.

APV: Investment costs, economics and potential

Adapted from Fraunhofer ISE (2021)

From an economic perspective, the installation of agrivoltaic systems on cropland is more expensive than ground-mounted systems, but comparable to small-scale rooftop PV. The costs across the lifetime (20 years) are averaging around 6.5 ct/kWh for a system on permanent crops (low clearance height) and around 10 ct/kWh for a mounted system (up to 6 meters above the ground) (Fraunhofer ISE 2020). If the electricity can be used at the site, it will therefore be cheaper than the grid in most areas. As can be seen in the illustration, the levelized costs of electricity are on average lower than most conventional energy carriers.

The higher costs in comparison to a ground-mounted system stem mainly from the mounting structures and their installation on site. In a US study, even though crop yields minimally reduced, the total value generation of the croplands increased by 30% on average. (Dinesh and Pearce 2016) Some countries already introduced subsidies for APV systems. With further standardization, costs can be expected to slightly decrease. The additional benefits from increased harvests have not been quantified.

According to the FAO, 38% of global land surface is used for agriculture. About a third of this land is used as cropland (FAO 2020). Currently, this agrarian land demands for 70% of the globally available freshwater. With ongoing population growth however, it is expected that agricultural production will have to expand by around 70%. (The World Bank 2020) Especially in highly irrigated areas, the potential savings through APV are enormous.

Additionally, the potential for electricity generation are huge. In Germany, covering 4% of the agricultural area would be enough to cover the total national electricity demand (Fraunhofer ISE 2020).

Currently, the total capacity of agrivoltaics across the globae is around 2.8 GWpeak. The development shows an exponential increase. Agrivoltaics could prove to be one key technology to tackle multiple issues at once. With rising temperatures and less water availability, the relevance is likely to continue to increase over the next decades.

Fraunhofer ISE (2020)

Even though the levelized costs of electricity are comparatively low, the investment costs are still significant. The figure illustrates the costs of different items. According to these numbers the total costs are around 1,500 €/kWp for high-mounted systems and around 1.100 € for constructions with a low clearance height (Fraunhofer ISE 2020).

Especially for the areas of highest potential of synergetic effects, which are mainly located in the global south, this means significant investment costs, thus creating a high market entry barrier.

Additionally, the data availability for different crops in different regions is still lacking. Further research can be expected to further push the growth of agrivoltaics.

Case Study 1: Agrivoltaics Curacaví Chile, Site Conditions

Source: Microsoft Bing (2021), Jung & Salmon 2021 Source (both, right side): www.renewables.ninja and Gelaro et al. (2017)

Overall Setting

In a cooperative research project, Fraunhofer Chile, the local government, and local partners have implemented three agrivoltaic systems (each 13 kWp), including monitoring devices in the surroundings of Santiago de Chile (El Monte, Curacaví, and Lampa). The study aims to create insights on crop benefits from reduced solar radiation and the adaption and optimization of agrivoltaics for specific climatic and economic conditions.

Biophysical Site Conditions

Typical for the central Chile region, the case study in the commune of Curacaví in the West of Santiago de Chile (-33.503917, -70.995556) has high annual solar radiation (2191 kWh∕m² in 2019, Gelaro et al. (2017)) and low annual precipitation (average 511 mm/a, 96.6 mm∕a in 2019, Gelaro et al. (2017)). Average high temperatures range between 18°C in June and 31°C in January, while average low-temperature range between 6°C in June and 15°C in January.

The pilot is installed on a horticultural field at a height ranging from 202m to 203 m above sea level featuring a slight slope from east to west, enabling irrigation by gravitation (Jung and Salmon 2021). Applying the Soil Classification Triangle (Cornell University 2010), the topsoil can be identified as sandy to medium loam (~ Sand: 525, Clay: 178, Silt: 297 g∕kg in the upper 1.5 m, Soilgrids); indicating good natural fertility and relatively good moisture retention (Hengl et al. 2017).

WEF challenges, tradeoffs, and demands In general, the El Niño Southern Oscillation leads to high climate variability. The “Mega Drought” in the region led to a reduction of precipitation by 25 to 45 percent in the last ten years (Garreaud et al., 2019). The increasing water and energy demand of the metropolitan region of Santiago de Chile and intensifying agricultural practices face water scarcity in the Maipo basin (Meza et al., 2015).

The water scarcity and high demand lead to competition for water from different sectors, including water for residential drinking and sanitation, irrigation, and hydropower production (ebd., NS Energy). Due to the hydroclimatic conditions, local scale farmers look for ways to tackle heat stress and dry out their plants.

Electrical yield and electricity cost estimation (Curacaví)

Source: Fraunhofer ISE (2020)

Yield Frauenhofer (2020) applied the photovoltaic yield model of renewables.ninja for the given set-up and coordinates: The annual energy production sums up to 18899 kWh for 2019 (Pfeinninger and Staffell). Monthly maximas are in the southern hemisphere’s summer (December, January), and monthly minimas in the southern hemisphere’s winter (June, July). The observed electricity production from April 2019 to March 2020 sums up to 8157 kWh (Jung and Salmon 2021). The big difference in annual production can mainly be explained by a defect and measurement shortcomings on-site:

-

Defect: Inverter did not produce energy from 9th of September to 22nd of October 2019

-

Electricity production is higher in winter than in summer, potentially power capacity loss due to the defect in September

-

Days of zero electrical yield in May and June (error)

Thereby the maximum power values are very similar:

- renewables.ninja: 10.29 kW; 3rd of January, 11 am to 12 am; measured on site: 10.32 kW, 8th. September 2019, 4 pm to 5 pm

The crop yield is estimated to remain at conventional levels through reduced heat stress & sunburn and increased soil moisture provided by shading while ensuring sufficient provision of sunlight.

The multiple land-use benefits of Agrivoltaics can be expressed through the land equivalent ratio (LER). The LER is the sum of the respective yield ratios of dual land use to mono land use (Mead and Willey 1980; Trommsdorff et al. 2021):

LER= (Yield_a (dual))/(Yield_a (mono))+(Yield_b (dual))/(Yield_b (mono))

Cost Estimation The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) estimations by Fraunhofer ISE (2020) can be applied to approximate the estimate of the LCOE for the APV Curacaví. Given the medium clearance height of 4m, the high solar potential on-site, and assuming the availability of all components at global market prices, we estimate the LCOE to be around 7 €-ct/kWh. Considering Chilean households’ electricity price of 0.156 €-ct/kWh (143 CLP/kWh, http://globalpetrolprices.com/ (2020)), expenditure savings can be reached through self-consumption. Furthermore, considering additional income through crop sales or self-consumption, we assume that agrivoltaics can benefit smallholder farmers in Chile.

APV: Technology, Components and Performance

Jung and Salmon (2021); Fraunhofer ISE (2020)

Technologies & System Components

The main components of the Agrivoltaic System are photovoltaic panels, inverters, crops, and the mounting structure:

-

Photovoltaic Panels Photovoltaic cells within the photovoltaic panel convert the sunlight’s energy to electric energy using the photovoltaic effect (Rappaport, 1959). At the Curacaví case study, 48 panels from Jinko Solar, with a capacity of 260 Wp each and a maximum efficiency of 16.19%, are installed. Overall, they sum up to a total panel surface area of 76.8 𝑚^2 and provide a peak power of 12.48 kWp. The azimuth of the panels is 295° NW, in line with the field’s orientation, and an inclination of 27°. This alignment allows a homogenous light distribution underneath the PV panels (Jung & Salmon, 2021).

-

Inverters Inverters convert the direct current (DC) from the photovoltaic panels into alternating current (AC). Alternating current is widely used to power most of our devices. However, many devices (light bulbs, USB-charger, refrigerator, TV) exist as DC versions. Thus, inverters and their conversion losses can be omitted by fully relying on DC devices. At the Curacaví Agrivoltaic Project, three inverters of 2.5 kWp and one inverter of 10 kWp are installed. They are connected to four different beneficiaries applying the local net-billing policy.

-

Crops In the case study, broccoli, cauliflower, and herbs are cultivated. Broccoli & cauliflower rather prefer sunny but mild climates.

-

Mounting Structure The mounting structure for the photovoltaic system’s elevation consists of galvanized metal posts and is based on concrete. The structure elevates the photovoltaics panels and allows a clearance height of 3,5 m so that agricultural machinery, especially tractors, can be deployed below (Jung & Salmon, 2021).

-

Overall dimensions The overall height of the installation reaches 4.78 m. The agrivoltaic system is formed by tree sub-structure modules whit a width of 8 m and a length of 6.9 m adding up to a total length of 28 m, leading to a total area of 224 𝑚^2 The width of 8 m was chosen to meet the dimensional demands of the deployed agricultural machines (Jung & Salmon, 2021).

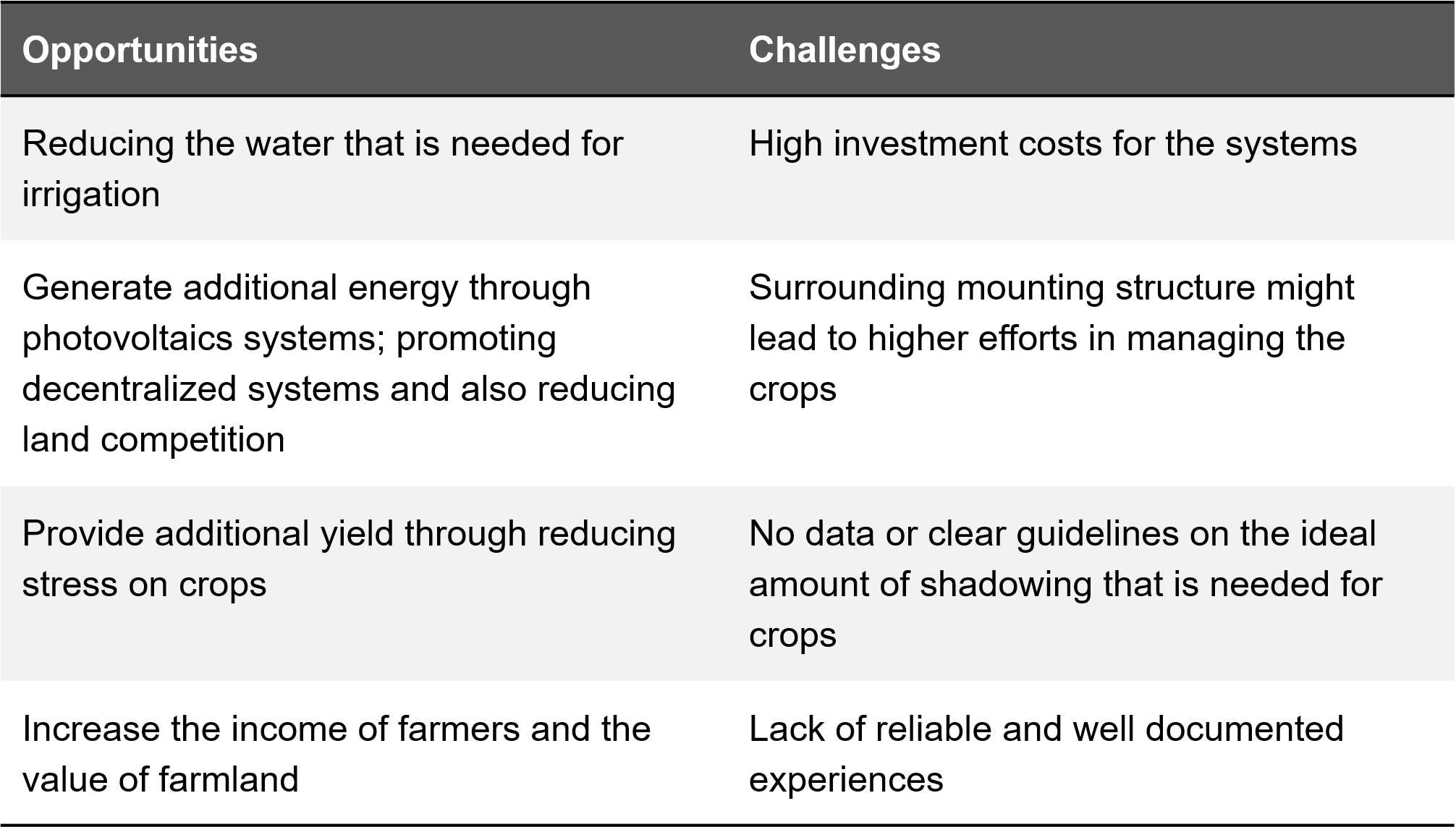

Summary Agrivoltaics

Agrivoltaics brings opportunities to improve every aspect withtin the WEF Nexus. Furthermore, it can reduce competition for landuse and increase the income of farmers. It is however a rather new technology, where further research is needed.

As Weselek et al. (2019) put it:

„As only very few studies address the impact of this technology on crop yields and quality, further investigations incorporating different climatic conditions, crop species and varieties are indispensable for the evaluation of its applicability in prospective agricultural system”

Next solution: Irrigation Systems

References

Cornell University (2010) Northeast Region Certified Crop Adviser: Nutrient Management. Competency Area 2: Basic Concepts of Soil Fertility. https://nrcca.cals.cornell.edu/nutrient/CA2/CA2_SoftChalk/CA2_print.html

Garreaud RD, Boisier JP, Rondanelli R, Montecinos A, Sepúlveda HH, Veloso‐Aguila D (2019) The Central Chile Mega Drought (2010–2018): A climate dynamics perspective. Int J Climatol 40:421–439. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6219

Gelaro R, McCarty W, Suárez MJ, Todling R, Molod A, Takacs L, Randles CA, Darmenov A, Bosilovich MG, Reichle R, Wargan K, Coy L, Cullather R, Draper C, Akella S, Buchard V, Conaty A, da Silva AM, Gu W, Kim G-K, Koster R, Lucchesi R, Merkova D, Nielsen JE, Partyka G, Pawson S, Putman W, Rienecker M, Schubert SD, Sienkiewicz M, Zhao B (2017) The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Climate 30:5419–5454. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1

Hengl T, Mendes de Jesus J, Heuvelink GBM, Ruiperez Gonzalez M, Kilibarda M, Blagotić A, Shangguan W, Wright MN, Geng X, Bauer-Marschallinger B, Guevara MA, Vargas R, MacMillan RA, Batjes NH, Leenaars JGB, Ribeiro E, Wheeler I, Mantel S, Kempen B (2017) SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12:e0169748. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169748

Meza FJ, Vicuna S, Gironás J, Poblete D, Suárez F, Oertel M (2015) Water–food–energy nexus in Chile: the challenges due to global change in different regional contexts. Water International 40:839–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2015.1087797

Microsoft Bing (2021): Aerial View. Terms of Use: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/maps/product/print-rights

NS Energy Alto Maipo Hydroelectric Power Project. https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/alto-maipo-hydroelectric-power-project/

Jung, D., & Salmon, A. (2021). Agrivoltaic Pilot Plant Curacavi: General Information and Technical Description. Fraunhofer CSET.

Electrical yield and electricity cost estimation (Curacaví) Frauenhofer ISE (2020). Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition. A Guideline for Germany. Freiburg. Fraunhofer ISE. https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/en/documents/publications/studies/APV-Guideline.pdfGlobalPetrolPrices.com. (2020). Retail energy price data. globalpetrolprices.com

Jung, D., & Salmon, A. (2021). Agrivoltaic Pilot Plant Curacavi: General Information and Technical Description. Fraunhofer CSET.

Mead, R., & Willey, R. W. (1980). The concept of a ‘land equivalent ratio’ and advantages in yields from intercropping. Experimental Agriculture, 16(3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479700010978

Pfeinninger, S., & Staffell, I. Renewables.Ninja. https://www.renewables.ninja/

Trommsdorff, M., Kang, J., Reise, C., Schindele, S., Bopp, G., Ehmann, A., Weselek, A., Högy, P., & Obergfell, T. (2021). Combining food and energy production: Design of an agrivoltaic system applied in arable and vegetable farming in Germany. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 140, 110694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110694

APV: Technology, Components and Performance + Summary

Adeh, E. H., Good, S. P., Calaf, M., & Higgins, C. W. (2019). Solar pv power potential is greatest over croplands. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 11442. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47803-3

Barron-Gafford, G. A., Pavao-Zuckerman, M. A., Minor, R. L., Sutter, L. F., Barnett-Moreno, I., Blackett, D. T., Thompson, M., Dimond, K., Gerlak, A. K., Nabhan, G. P., & Macknick, J. E. (2019). Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nature Sustainability. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0364-5

Bellini, E. (2020). Giant agrivoltaic project in china. https://www.pv-magazine.com/2020/09/03/giant-agrivoltaic-project-in-china/

Chapin, F. S., Matson, P. A., & Vitousek, P. M. (2011). Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9504-9

Dinesh, Harshavardhan; Pearce, Joshua M. (2016): The potential of agrivoltaic systems. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 54 (2), pp. 299–308. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.024

Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe (2020): Basisdaten Bioenergie Deutschland 2021. Available online at https://www.fnr.de/fileadmin/Projekte/2020/Mediathek/broschuere_basisdaten_bioenergie_2020_web.pdf, checked on 10/25/2021.

FAO (2019): The future of food and agriculture – Trends and challenges. Available online at https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf, last checked on 10/26/2021

FAO (2020): Land use in agriculture by the numbers. Available online at https://www.fao.org/sustainability/news/detail/en/c/1274219/, checked on 10/25/2021

Fraunhofer ISE. Apv-maga: agrivoltaics for mali and gambia: Sustainable electricity production by integrated food, energy and water systems. https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/research-projects/apv-maga.html(2020). Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition. A Guideline for Germany. Freiburg. Fraunhofer ISE. https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/en/documents/publications/studies/APV-Guideline.pdf

Fraunhofer ISE (2020): Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition.

Fraunhofer ISE (2021): Levelized Cost of Electricity Renewable Energy Technologies. June 2021.

Hassanpour Adeh, E., Selker, J. S., & Higgins, C. W. (2018). Remarkable agrivoltaic influence on soil moisture, micrometeorology and water-use efficiency. PLOS ONE, 13(11), e0203256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203256

IRENA (2018): Global Energy Transformation – A Roadmap to 2050. Available online at https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2018/Apr/IRENA_Report_GET_2018.pdf, checked on 10/26/2021

Jung, D., & Salmon, A. (2021). Agrivoltaic Pilot Plant Curacavi: General Information and Technical Description. Fraunhofer CSET.

Runkle, E. (2015): Interactions of Light, CO2 and Temperature on Photosynthesis. Edited by Michigan State University. Available online at https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/resources/pdfs/light-co2-and-temp.pdf, checked on 10/25/2021

Trommsdorff, M., Kang, J., Reise, C., Schindele, S., Bopp, G., Ehmann, A., Weselek, A., Högy, P., & Obergfell, T. (2021). Combining food and energy production: Design of an agrivoltaic system applied in arable and vegetable farming in Germany. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 140, 110694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110694

Touil, Sami; Richa, Amina; Fizir, Meriem; Bingwa, Brendon (2021): Shading effect of photovoltaic panels on horticulture crops production: a mini review. In Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 20 (2), pp. 281–296. DOI: 10.1007/s11157-021-09572-2

Weselek, Axel; Ehmann, Andrea; Zikeli, Sabine; Lewandowski, Iris; Schindele, Stephan; Högy, Petra (2019): Agrophotovoltaic systems: applications, challenges, and opportunities. A review. In Agron. Sustain. Dev. 39 (4), p. 545. DOI: 10.1007/s13593-019-0581-3

The World Bank (2020): Water in Agriculture. Available online at https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water-in-agriculture#1, checked on 10/25/2021

The World Bank (2020): Water in Agriculture. Available online at https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water-in-agriculture#1, checked on 10/25/2021