7.3.8 Anaerobic digestion and biogas

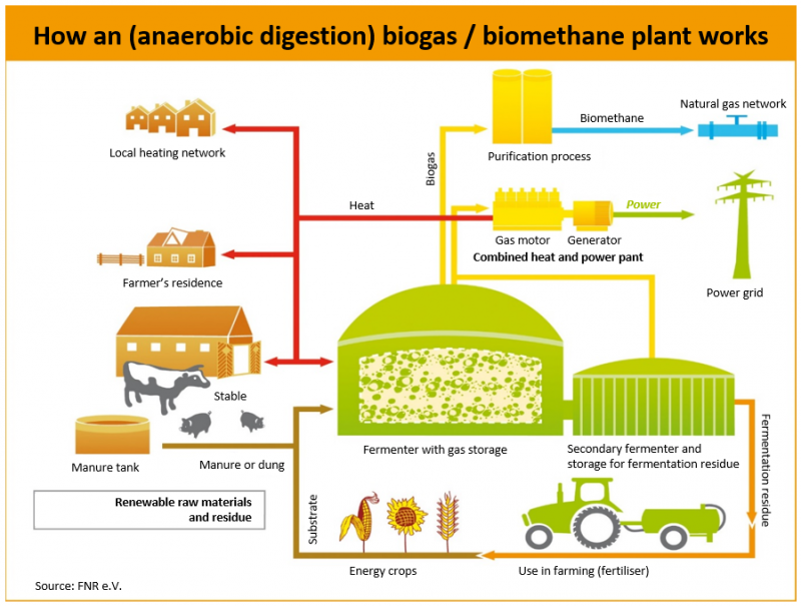

Source: FNR (2016)

Source: FNR (2016)

Introduction

Anaerobic digestion describes the decomposition of organic matter by microbes in the absence of oxygen. During this process of decomposition, biogas consisting primarily of CO2 and CH4 (methane) is released. The digestion takes place in a gas-tight reactor or fermenter, which is designed for this purpose and offers favorable conditions for the growth of micro bacteria. The gas is extracted from the fermenter and can be burned or used for electricity generation. Co-generation (the use of both heat and power) in combined heat power plants is very common in biogas utilization. After the decomposition, the residues from the fermenter can be used as fertilizer on fields, due to their high mineral content (FNR 2016).

Biogas capacities and usage

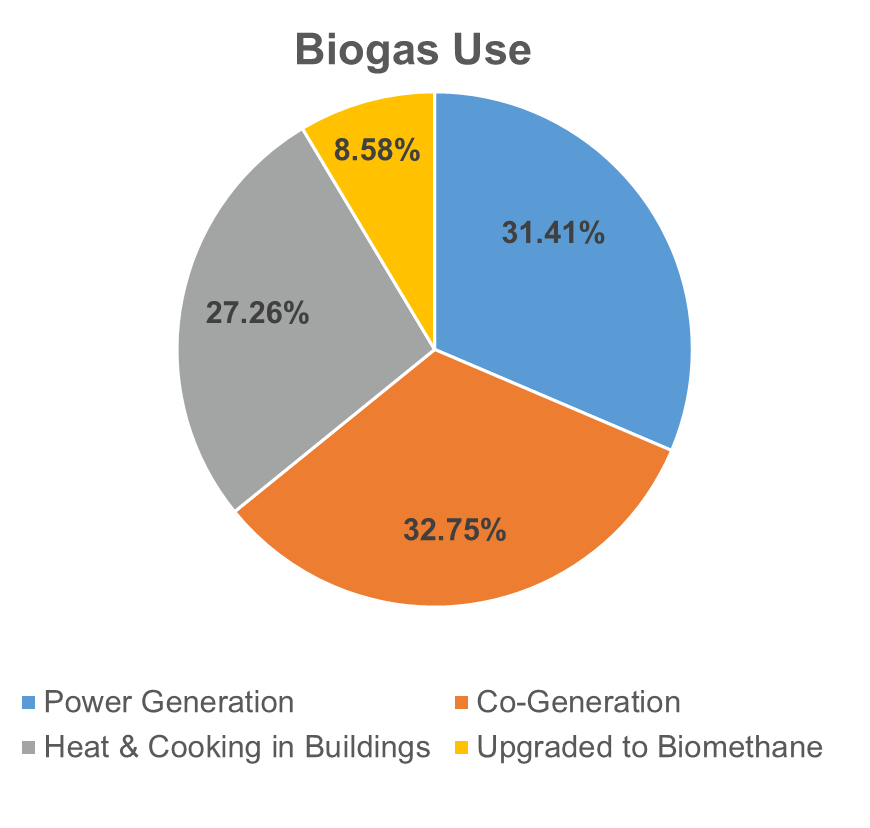

Source: IEA 2020

Source: IEA 2020

Global biogas production has been increasing significantly within the last 10 years. Currently, the production capacity ranges around 33 Mtoe (For comparison, Germany’s total energy demand was around 290 Mtoe in 2020 (BP 2021)). Europe and Germany in particular are responsible for the biggest share (IEA 2020). Around one third of the produced biogas is used for cogeneration (also called CHP – combined heat and power); another 31% is used solely for power generation. 27% is used to provide heat indoors and 8.5% are upgraded to biomethane, which can be distributed in the gas grid like natural gas (IEA 2020).

Types of feedstock

Biowaste to Biogas - GIZ

Biowaste to Biogas - GIZ

Feedstock for biogas production The first step in the production of biogas is the procurement and management of the feedstock. This step includes the delivery, storage, processing, preparation and injection into the fermenter. Generally, all types of organic material have energetic value. One major restriction of anaerobic digestion however is that material with high lignin contents, meaning most wooden residues, cannot be used in greater amounts because they hinder the process of decomposition. Here, aerobic digestion (=composting) is preferred. (Fachverband Biogas and GIZ 2019)

This section illustrates the different sources of digestable substrate.

Starting the process Before the digester is put into operation, it must be provided with a sufficient quantity of suitable bacteria. In simple setups, cow dung diluted with water is containing suitable microorganisms and can be used for this purpose. It should be ensured that at least one tenth of the fermenter is filled with the manure-water mixture. More mass here means a larger number of bacteria and, in the further course, faster biogas formation. The fermentation substrate should then be added gradually so that the bacteria can adapt at a sufficient rate. (Deublein and Steinhauser, 2010)

In order for the fermentation substrate to be pumpable, sufficient liquid must also be present. It is recommended to keep the dry content below 12 to 15 percent. For this purpose, the organic waste should be mixed with waste water. The use of fresh water is not economical and increases trade-offs (FNR 2016). When using organic waste in countries of lower income, the rule of thumb is to mix one part organic waste with two parts wastewater (Vögeli et al. 2014). For calculating the ideal amount of water in industrial plants, more adequate methods are are available (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009)

The substrate should not consist of too much foreign substances. Furthermore, decreasing the size of pieces in the substrate can increase the biogas yield, as it increases the surface area for the bacteria. (Vögeli et al. 2014) In high tech biogas plants, additional prior treatment exists.

What part of the feedstock is used?

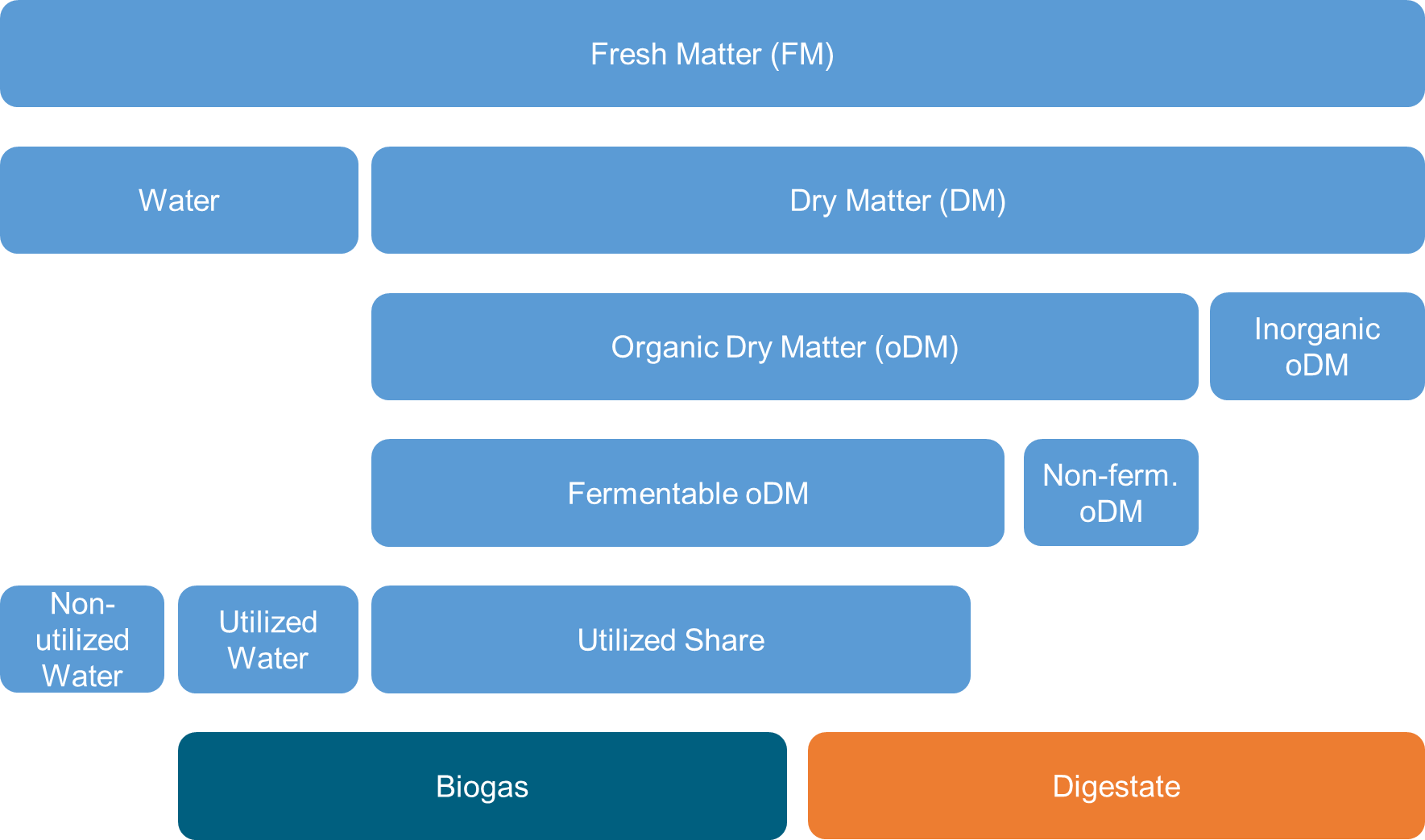

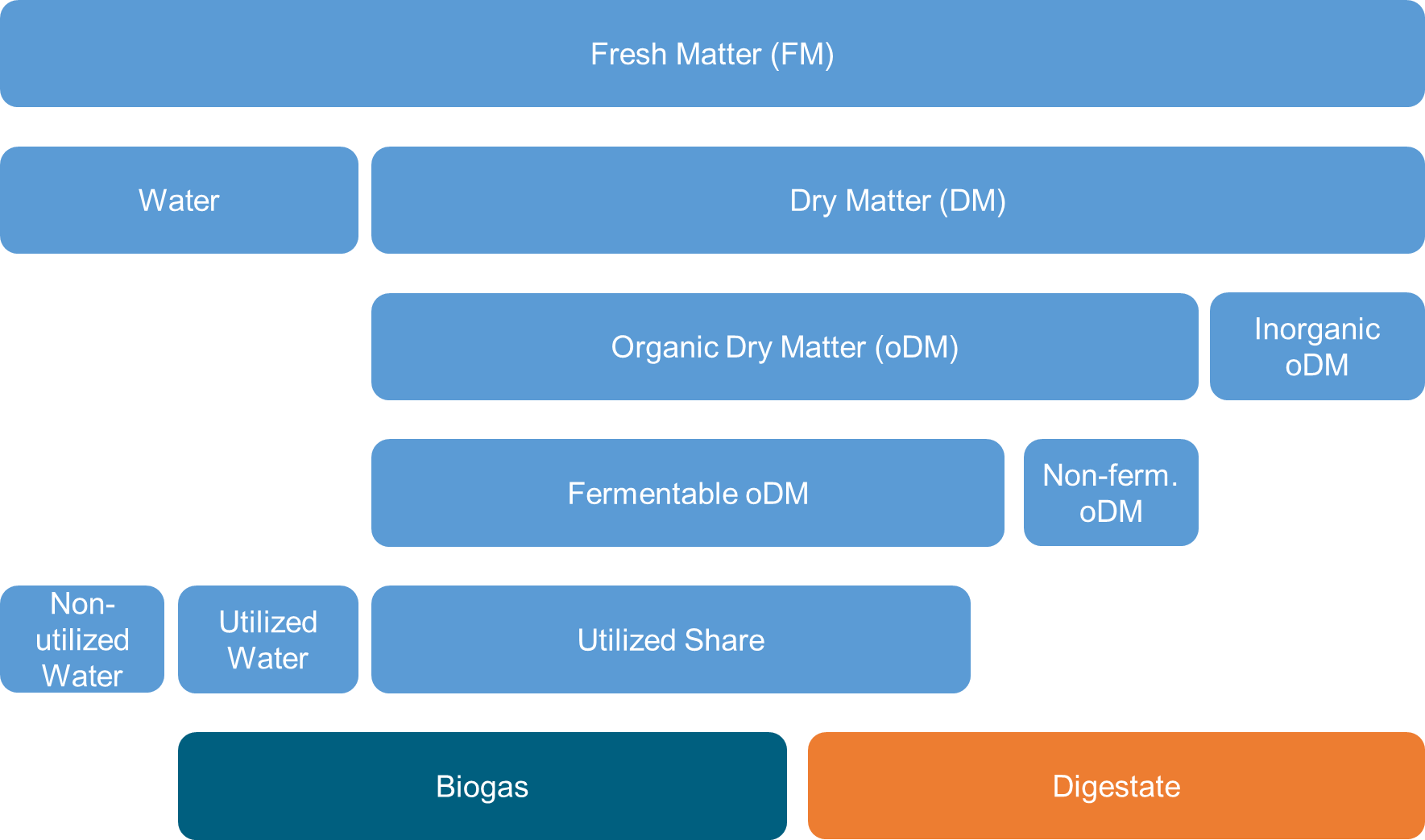

Kaltschmitt et al. 2009; design adapted from Felix Mayer M.Sc.

Kaltschmitt et al. 2009; design adapted from Felix Mayer M.Sc.

Regardless of the source of the input, when looking at the process of anaerobic digestion, the digestate is always made up of dry matter and water. The dry matter can be further broken down into organic dry matter (oDM) and inorganic dry matter. The oDM also has fermentable and non-fermentable parts. The share that is actually utilized from the fermentable parts serves to produce biogas, along with the utilized water. The remaining parts of the dry matter can be reused as a mineral fertilizer (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009).

Different options in biogas production

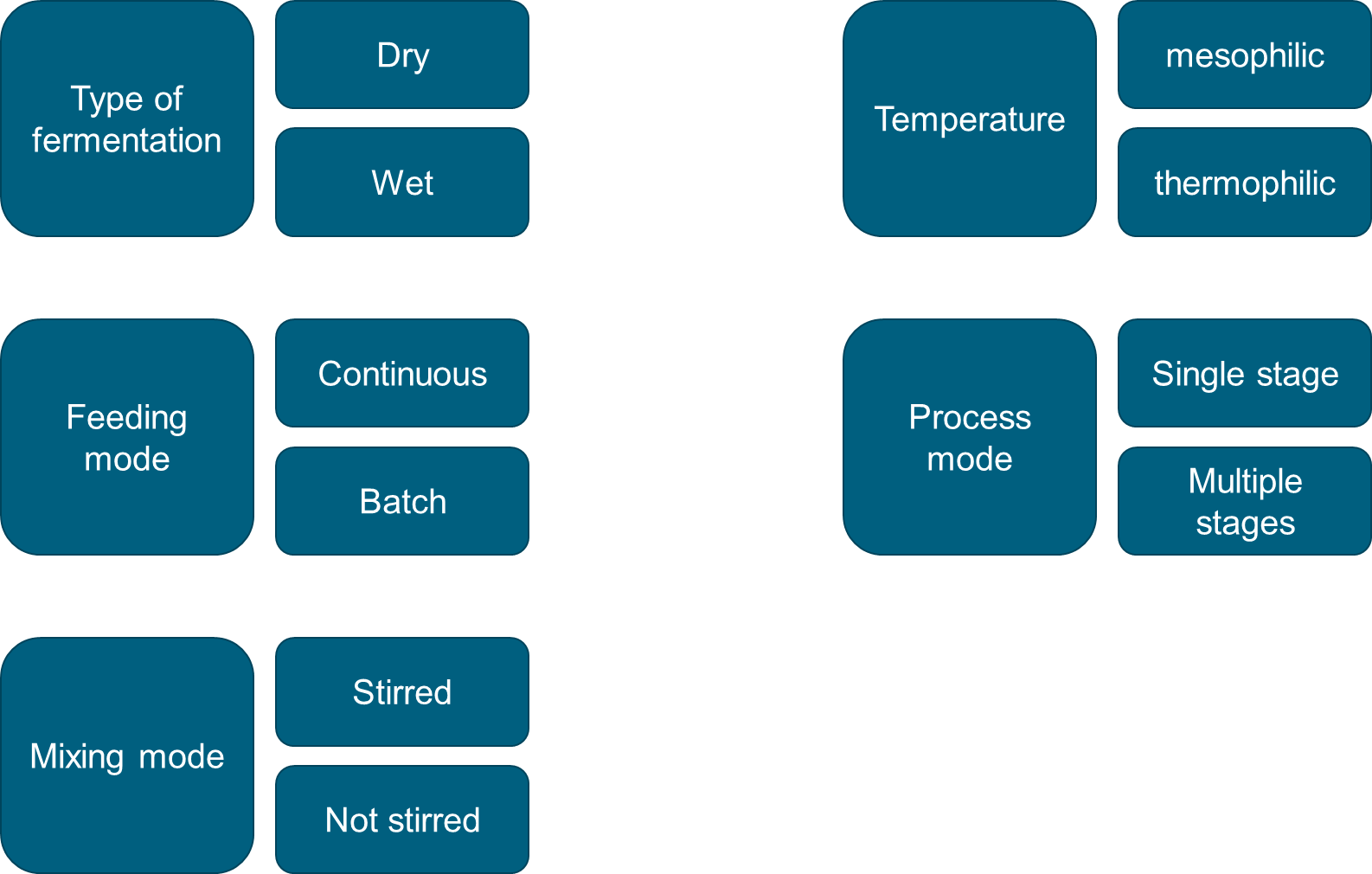

There are various parameters within the operation of a biogas plant, that steer the process of bacterial decomposition. The most important ones are illustrated here.

Type of fermentation The type of fermentation is mainly decided by the percentage of dry matter within the substrate. Wet fermentation is characterized by a low content of solids in the substrate (water > 90%), In dry fermentation, dry solids take up between 15 and 35% (Stolze et al. 2015). In wet fermentation, the substrate is usually pumpable, whereas in dry fermentation it is not (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009).

Feeding mode The batch mode describes a process where the fermenter is filled and sealed until the extraction of the gas. This allows for the highest yield, since the extraction happens only when the fermentation has finished. Continuous feeding describes the process where freshmatter is constantly added, while at the same time, the same amount of digestate is removed. This allows for higher amounts of input, but the efficiency decreases, since parts of the substate get taken out before the maximum yield can be extracted (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009).

Mixing mode Most fermenters are continuously stirred. This increases the energy demand for biogas production but in turn serves to increase the expected yields. Depending on the setup, fermenters do not have to be stirred or it’s simply cheaper not to stir them (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009).

Temperature Increasing the temperature inside the fermenter generally serves to fasten the process of anaerobic digestion. There are various ranges of temperature, which are most favourable for the growth rate of different kinds of bacteria. For biogas production, the most important ones are mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria. For mesophilic ones, the ideal temperature for bacteria growth is between 35 and 43°C. The ideal temperature for the growth of thermophilic bacteria lies at 57°C. The advantage of mesophilic bacteria is that the process is more stable Thermophilic bacteria show an ever greater conversion rate (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009)

Process mode Depending on the appliance, it can make sense to physically separate different stages of fermentation. The aim here would be to optimize every step of the process and adjust the size of components within the single steps. Furthermore, setups with multiple fermenters connected in series exist (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009).

Production of Biogas – from high tech to low tech

Source: (1) Wikimedia commons, (2) UNIDO 2020, UNIDO Biogas Project

Biogas plants exist at both ends of the technology spectrum. While in countries such as Germany, many plants with a generating capacity of mulitple MW exist, fermenter sizes can be scaled down to only digest kitchen wastes of households (for a popular design, see e.g. https://www.homebiogas.com/) . In 2020 Germany had installed a total of 9,632 biogas plants, with a total electrical capacity of 5,666 MW (Fachverband Biogas 2021). In Nepal, where biogas plants are quite popular, reportedly more than 100,000 small scale plants exist, running mostly on organic waste (Müller 2007). Around the globe, there are close to 50 million small scale plants (World Biogas Association 2019).

The plant on the right does not feature any stirring, heating or the capacity to run different processing modes. The strong point of biogas plants however, is that biowaste is available virtually anywhere and the biogas production itself is technologically easy. Furthermore simple designs are quite cheap to implement. A publicly available blueprint from the Nepal Biogas Association, supported by the GIZ, shows the steps to build a fermenter with a total volume of 4 cubic meters. It deciphers the total costs at around 550 € (NBPA 2015).

Biogas yield

The methane yield in anaerobic digestion differs from crop to crop. Depending on the yield and on the local policies, it can be profitable to grow crops solely for energetic use. In Germany, the total area that was used to cultivate energy crops 2019 was at 2,310,000 hectares, making up for 14% of the total agricultural area (FNR 2021; Statistisches Bundesamt 2021). The use of agricultural land to cultivate energy crops increases concerns of water and food security and is subject to arguments. In terms of yield however, energy crops excel in comparison to residues from animals or plants, as highlighted in the graph. Waste on the other hand has a comparatively low specific yield, but is available in huge amounts.

In 2013, the FAO estimated a total volume of food wasteage alone at around 1.6 billion tons, or one third of global production. Most of this food ends in landfills. (FAO 2013) Additionally, there is wastewater, residues from harvest, human wastes etc. When looking at the Nexus approach, biogas could help to create energy from organic waste, decreasing the competition between food- and non-food crops. According to the World Biogas Association, the total amount of manure from cattle, buffaloes, pigs and chicken has the potential to generate over 3,000 TWh of electrical energy annualy, if anaerobically digested. This would be enough to supply 330 to 490 million people with power for the year (WBA 2019). The availability of biowaste everywhere can thus help to increase energy security, especially since biogas can be burned on simple stoves and is suitable for decentralized supply.

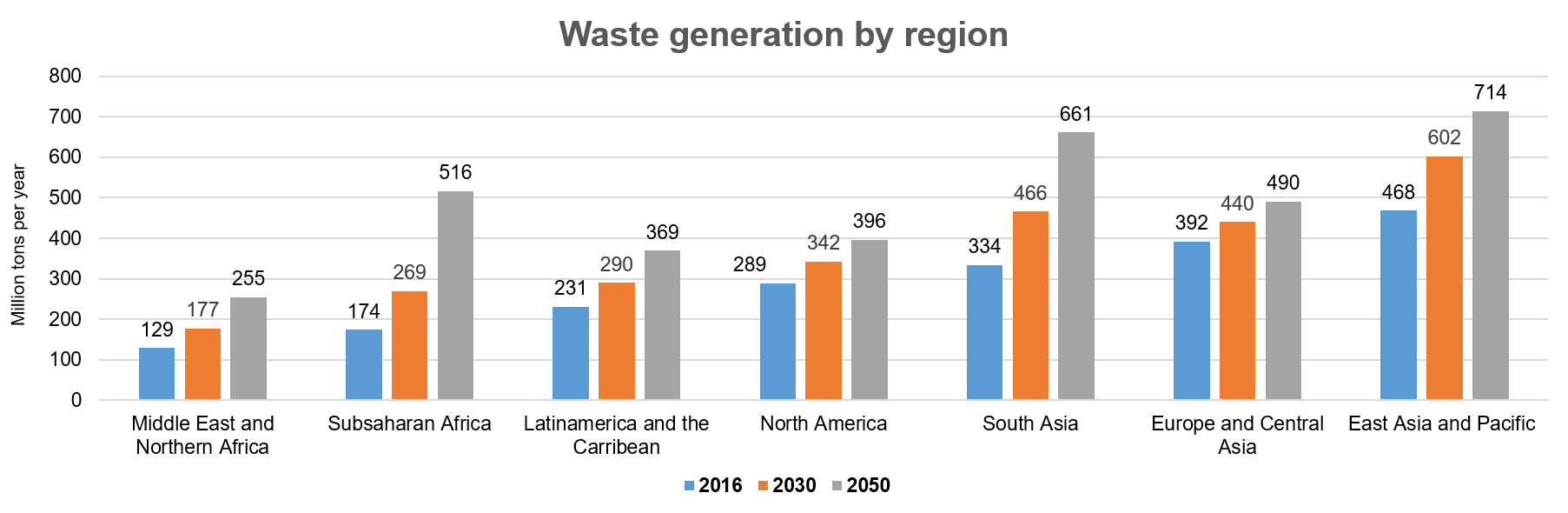

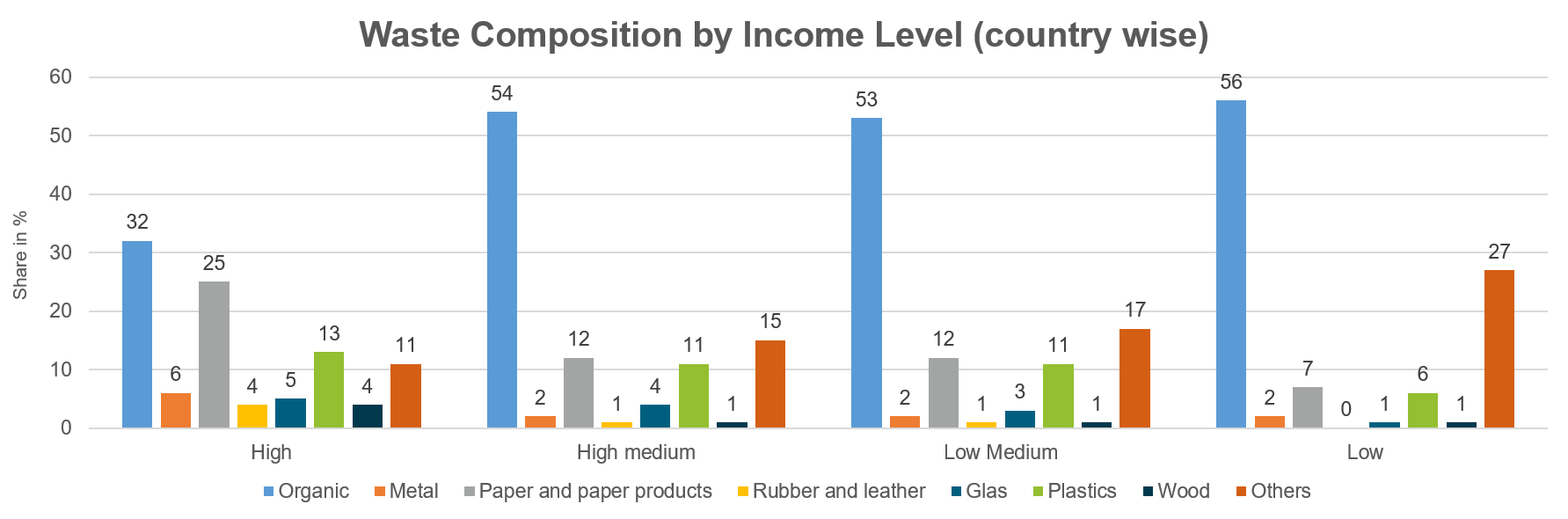

Biogas production and waste management

Potential of waste When looking at the global numbers and their projections, it can be seen that the total amount of waste is expected to almost double by 2050. Even though there are major differences between income levels of countries, the organic fraction always makes up for the largest share in the composition of waste (Kaza et al. 2018).

As most of it is thrown away right now, anaerobic digestion can also help to reduce stress on landfills and potentially decrease land requirements for it. Furthermore, anaerobic digestion decreases greenhouse gas emissions, since the methane is burned and converted to CO2, which is less potent as a greenhouse gas.

Challenges in waste management One major challenge is the collection and preparation of the waste, as currently the waste collection rates range from 96% (high income countries), to 51 % (lower-middle income) and 39% (low income) (Kaza et al. 2018). Additionally, especially in lower income countries, the biowaste may be used e.g. as animal feed, and thus has some value already.

Cleaning processes and storage

Sources: FNR 2016

Biogas consists of various components: Methane (50-75%); CO2 (25-45%); H2O (2-7%); H2S (<1%); N2 (<2%); O2 (<2%) and H2 (<1%). Additionally, there can be trace elements (FNR 2016). Depending on the use, proper processing can be necessary. While in countries of lower income and basic systems, the biogas is not properly processed, but rather burned for cooking and heat, some utilities require more effort. The most important cleaning processes are (FNR 2016):

- Water removal (= removal of H2O - avoid corrosion and increase energy content)

- Desulphurization (= removal of H2S - avoid the formation of SO2 during the combustion; H2S also leads to corrosion in engines)

If the biogas is to be fed into a gas grid, the CO2 content has to be reduced in addition. Various processes exist, that can increase the purity of the biogas to up to 96% methane (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009).

In order to storage biogas adequately, it should be compressed to save storage capacities.

Biogas to increase energy security

table: Kossmann et al. n.d.; cited from Vögeli et al. 2014

table: Kossmann et al. n.d.; cited from Vögeli et al. 2014

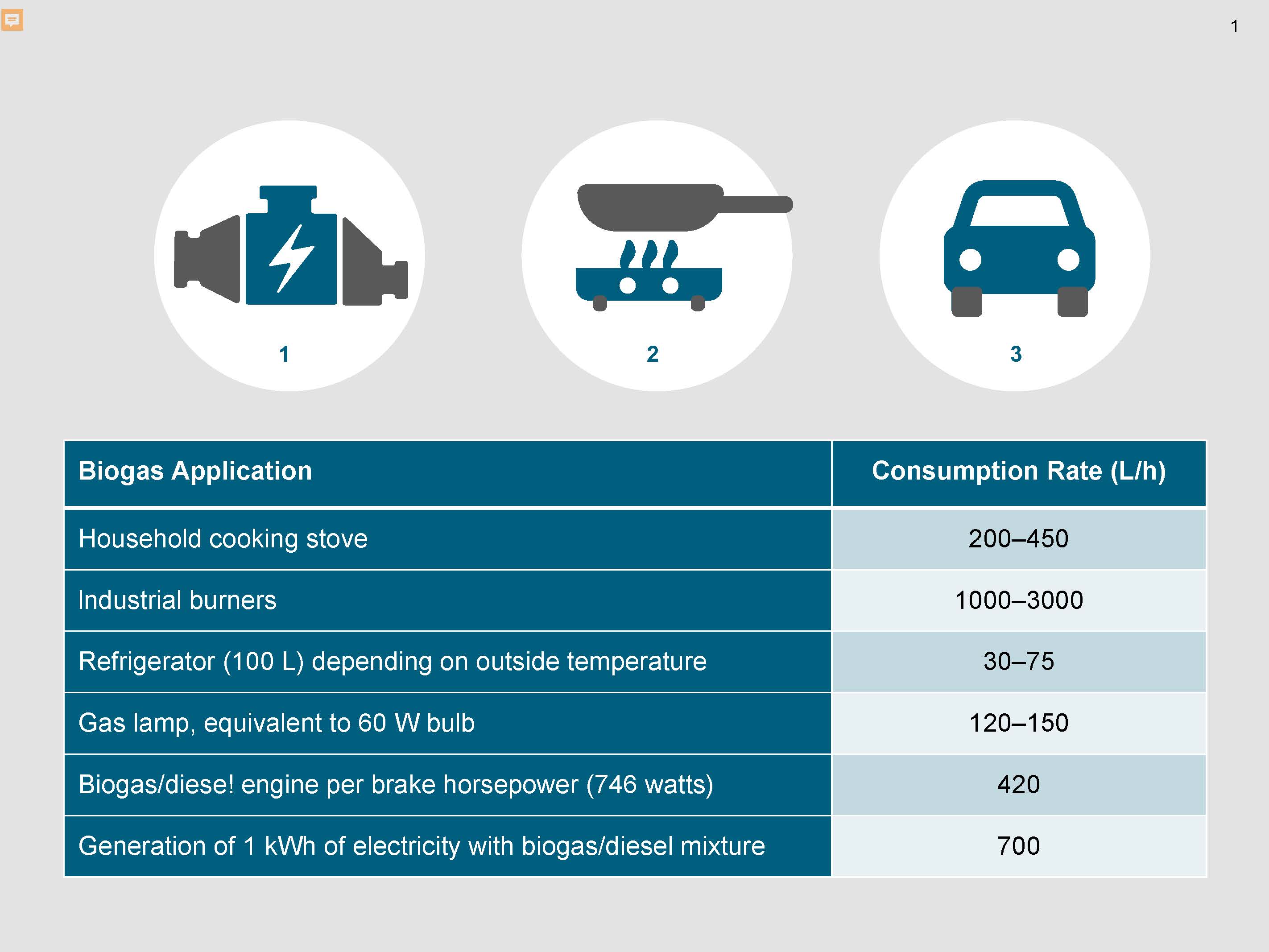

Anaerobic digestion can greatly increase energy security, since biogas is a non-fossil fuel that is easily storable and transportable. As shown in the previous sections, most biogas is used for power and/or heat generation. Furthermore, if the biogas is purified to biomethane, it can be injected into the natural gas grid or be compressed and used as a fuel for vehicles (Kaltschmitt et al. 2009).

Additionally, with low-tech solutions available, it can provide energy for heat in decentralized and rural settings. The table shows further usages, if the gas is not to be processed (Vögeli et al. 2014). (Putting the numbers into context: In a simple setup, 10kg of biowaste make for roughly 1m³ or 1000l of biogas (Vögeli et al. 2014)) When an increasing amount of biowaste is used, the land competition for energy crops and food-crops could potentially be reduced.

The co-production of nutrient-rich wet fertilizer can provide favorable conditions for crops and can substitute fossil-based products (Vögeli et al. 2014).

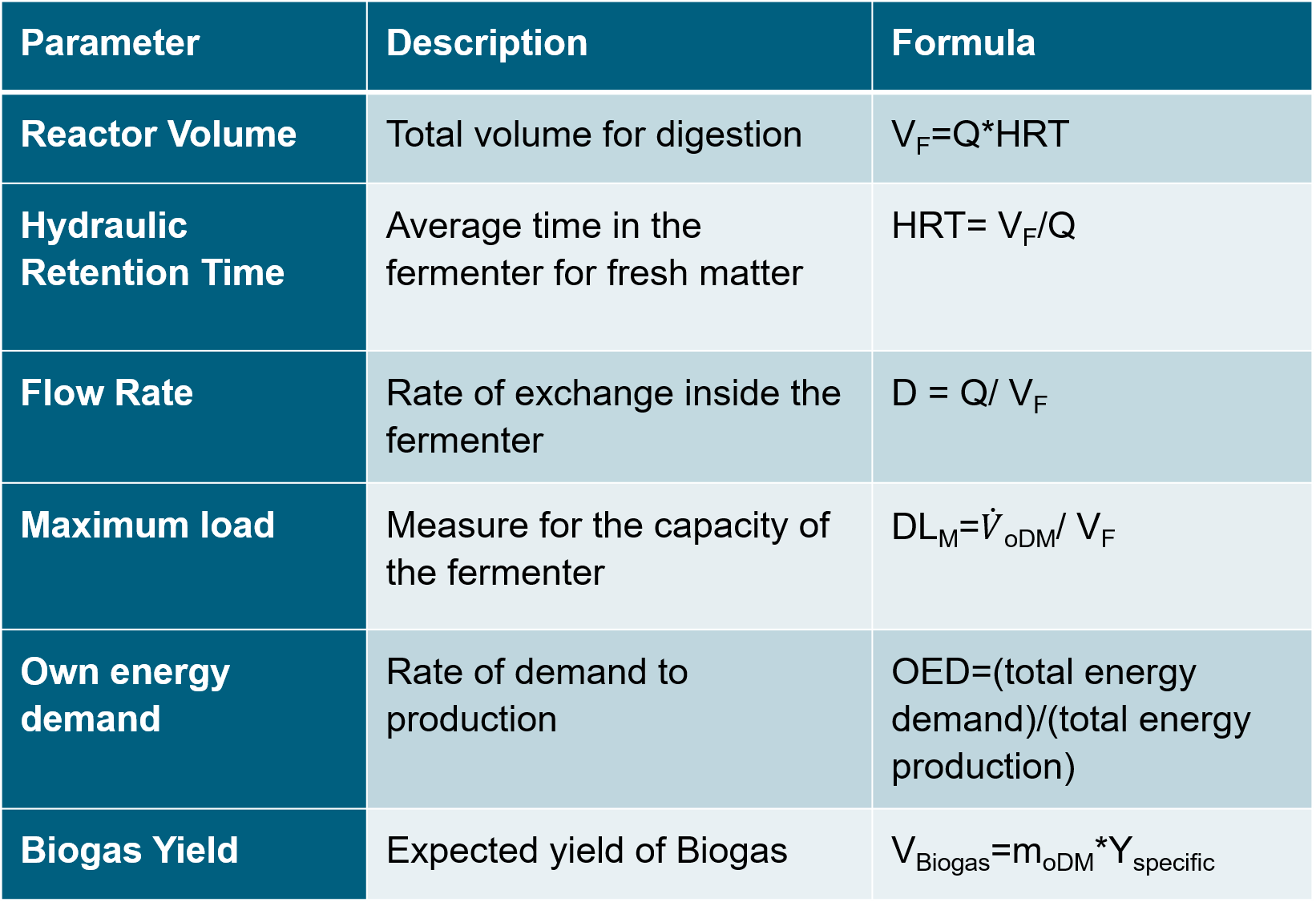

Parameters for calculations

Parameters to plan and construct a biogas plant (after Kaltschmitt et al. 2009)

Parameters to plan and construct a biogas plant (after Kaltschmitt et al. 2009)

- Volume of the Fermenter (VF) The volume of the fermenter defines the maximum amount of feedstock that can be inserted. It is the most important parameter for other calculations.

- Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) The HRT describes the timeframe, during which fresh substrate stays in the fermenter on average. It has to be adjusted in a way that there are always enough microbes and most digestion takes place before leaving the fermenter. It is defined as 𝐻𝑅𝑇=𝑉_𝐹/𝑄, where Q is the volume flow

- Flow rate (D) The flow rate is defined as the quotient of volume flow and total volume: 𝐷=𝑄/𝑉_𝐹 =1/𝐻𝑅𝑇 It is connected to the growth rate of bacteria, and has to be low enough as to not flush out the bacteria within the fermenter.

- Maximum digester load (DLM) The DLM is defined as the quotient of the organic dry matter load fed into the reactor over time (𝑉 ̇oDM) and the reactor volume VF and thus is a measure for the capacity of the fermenter. 𝐷𝐿_𝑀=𝑉 ̇_𝑜𝐷𝑀/𝑉_𝐹

- Energy use for operation The “own energy demand” is a measure for the efficiency of a plant and is defined by the ratio of 𝑂𝐸𝐷=((𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑟𝑔𝑦 𝑑𝑒𝑚𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛))/((𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑒𝑑 𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑟𝑔𝑦)) The total energy demand consists of the energy that is used to heat and to steer the fermenter, to utilize the pumps etc.

- Expected Biogas yield (VBiogas) The expected biogas yield is only related to the amount of organic dry matter that enters the system. From there on, different parameters like the composition of the substrate, the temperature, the rest time etc. define the actual yield. Considering the total input, the calculation is: 𝑉_𝐵𝑖𝑜𝑔𝑎𝑠=𝑚_𝐹𝑟𝑒𝑠ℎ𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟∗𝑟𝑠_𝑑𝑟𝑦𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟∗𝑟𝑠_𝑜𝑟𝑔𝑎𝑛𝑖𝑐𝑑𝑟𝑦𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟∗𝑌_𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑐 Where rs = relative share and Y_spec = specific yield in [m³/t_oDM]

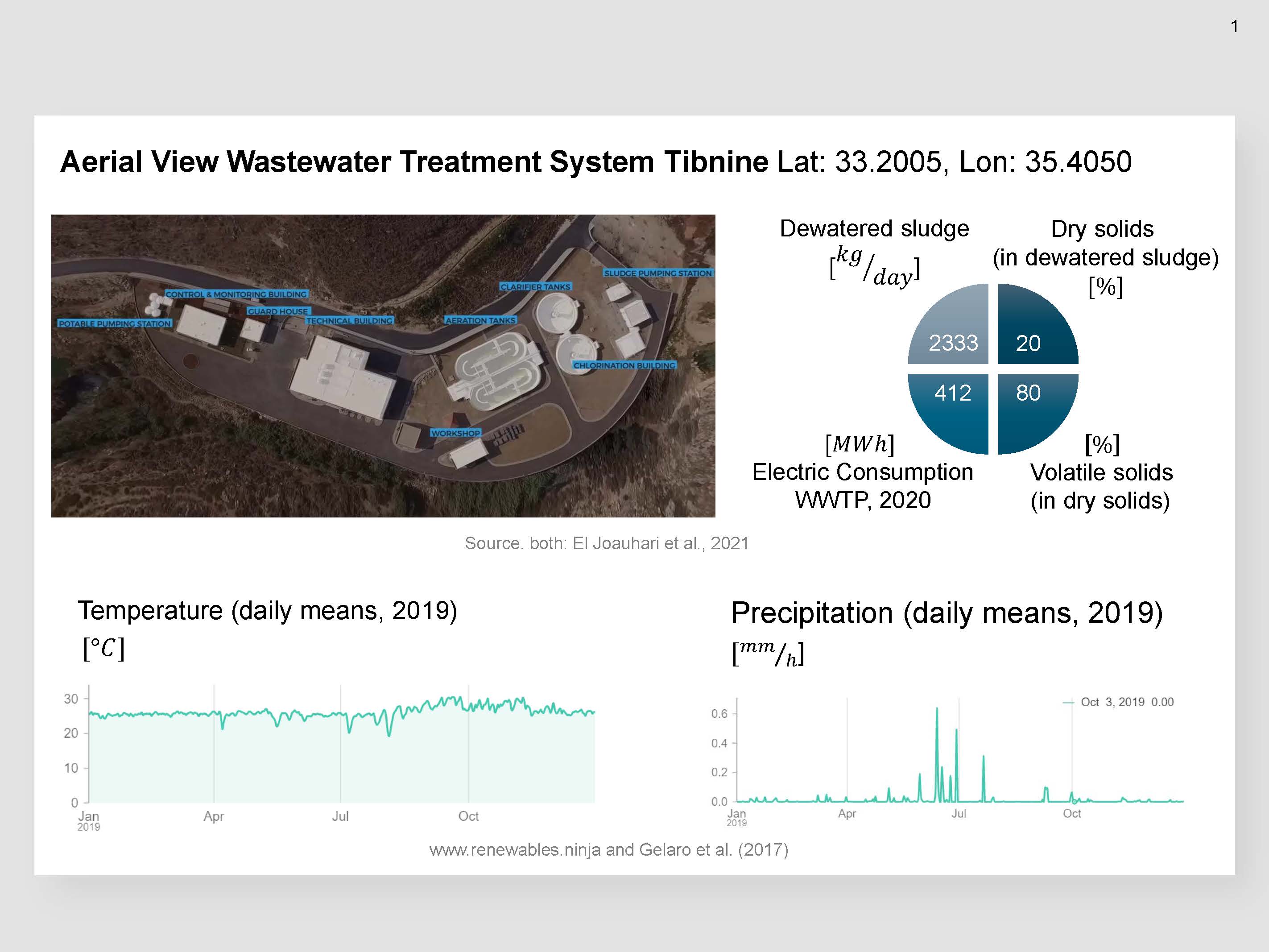

Case Study Tibnine, Site Conditions

www.renewables.ninja and Gelaro et al. (2017)

www.renewables.ninja and Gelaro et al. (2017)

Overall Setting The present case study is based on a final year project from students of Beirut Arab University (El Joauhari et al., 2021). The students investigated the potential of integrating anaerobic digestion as sludge treatment and renewable energy production process to Tibnine Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP), located at an altitude of 648 m above sea level in Bint Jbeil District in the South of Lebanon (33.2005, 35.4050).

Wastewater Treatment Plant Tibnine According to the case study data (El Joauhari et al., 2021), the wastewater treatment plant (WWPT) in Tibnine produces on average 2333 kg of dewatered sludge per day. The dry solid content in the dewatered sludge is 20%, and the volatile solid content in the dry solid content is 80%. The annual electricity demand of WWPT Tibnine in 2020 was 412 MWh.

Biophysical Conditions As anaerobic digestion is a heat-dependent process (e.g., bacterial growth rates) and wastewater treatment contributes to minimizing water pollution and increasing water availability, temperature, precipitation, and solar irradiance are crucial biophysical variables to consider in the design of wastewater-biogas systems. The average mean temperature in Tibnine is 19.12 °C ranging from an annual minimum of 4.9°C in winter to an annual maximum of 36.9 °C in summer in the year 2019, according to MERRA-2 data (Gelaro et al., 2017). Annual precipitation sums up to 463 mm, with precipitation events almost exclusively from October to April. High temperature and solar irradiance (annual: 2055 kWh/m²) lead to high potential evapotranspiration and arid summers.

Demands, Challenges, and Tradeoffs within the Water-Energy-Food Nexus

Population growth, inefficient and mismanaged water and energy grids, and the refugee crisis increased the pressure on water, energy, and food resources in Lebanon (Jaafar et al., 2019). The water availability is estimated to be 660 m³ per capita and year (Jaafar, 2021), thus just slightly above the level for “absolute” water scarcity at 500 m³ per capita and year (FAO). Refugee camps often face a lack of wastewater treatment. (Jaafar, 2021). Due to mismanagement and corruption, the national electricity utility - Électricité du Liban (EDL), covers only 63% of the national electricity demand resulting in rotating outages (Ahmad et al., 2020). The dysfunction of the national grid resulted in the development of thousands of informal and unregulated diesel generators (ebd.). Depleting aquifers and rising water demand further increase the electricity demand for groundwater pumping (Jaafar, 2021).

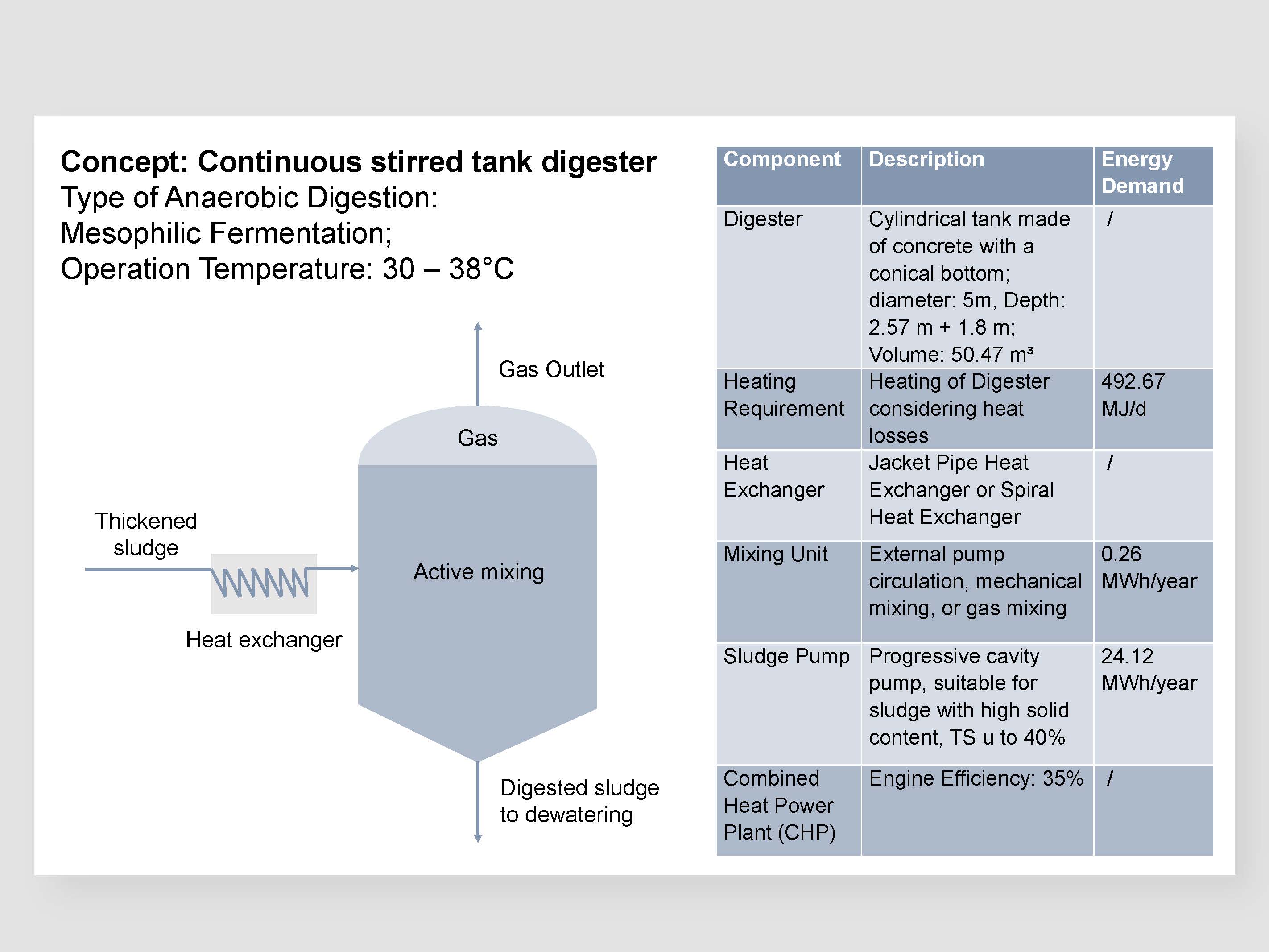

Biogas based on Wastewater: Technologies & Components

Source: El Joauhari et al. (2021)

Source: El Joauhari et al. (2021)

All following information is gathered from the final year project on renewable energy production from wastewater of students from the Arab University of Beirut (El Joauhari, Nassreddine, Mgharbel, & Izmerly, 2021).

Anaerobic Digestion integrated into Wastewater Treatment Anaerobic Digestion (AD) is integrated into the Wastewater Treatment Plant Tibnine as a sludge stabilization process consisting of successive stages of chemical and biochemical reactions in the presence of enzymes and mixed culture of microorganisms and the absence of O2. The process reduces the quantity of solids and destroys pathogens. The organics are converted into biogas (CH4+CO2), which can cover part of Tibnine WWTP’s energy needs, and digested sludge, which is piped to dewatering units of the WWTP.

Components: For the Tibinine case study, the students select mesophilic anaerobic digestion (operating at 30°C-38°C) using a continuous stirred tank reactor to maintain stable biological process conditions. Main components of the Biogas-wastewater system include the digester, combined heat and power plant (CHP), heat exchanger, mixing unit, and sewage pump:

The optimum volume of the digester calculates as the product of the volumetric flow rate of dewatered sludge and the set solid retention time and sums up to 50.47 m³. Heating requirements for the digester and heat loss at the digester walls sum up to 492.67 MJ/d. They are covered by a combined heat and power plant, considering an engine efficiency of 35%. Jacket Pipe Heat Exchanger or Spiral Heat Exchanger can be deployed as a heat exchanger between CHP and sludge cycle. Mixing the sludge in the digester is required to create uniformity throughout the digester, preventing the formation of the surface scum layer and the deposition of suspended matter. Existing mixing methods include external pump circulation, mechanical mixing, and gas mixing. The mixing method is not specified in the Tibnine case study. The energy demand of the mixing unit is estimated to be 5.27 – 7.9 W/m³, resulting in an electrical energy demand for mixing of 0.16 MWh/year. For pumping the sludge, a progressive cavity pump is used. The electrical demand of the pump is estimated to be 24.12 MWh/year.

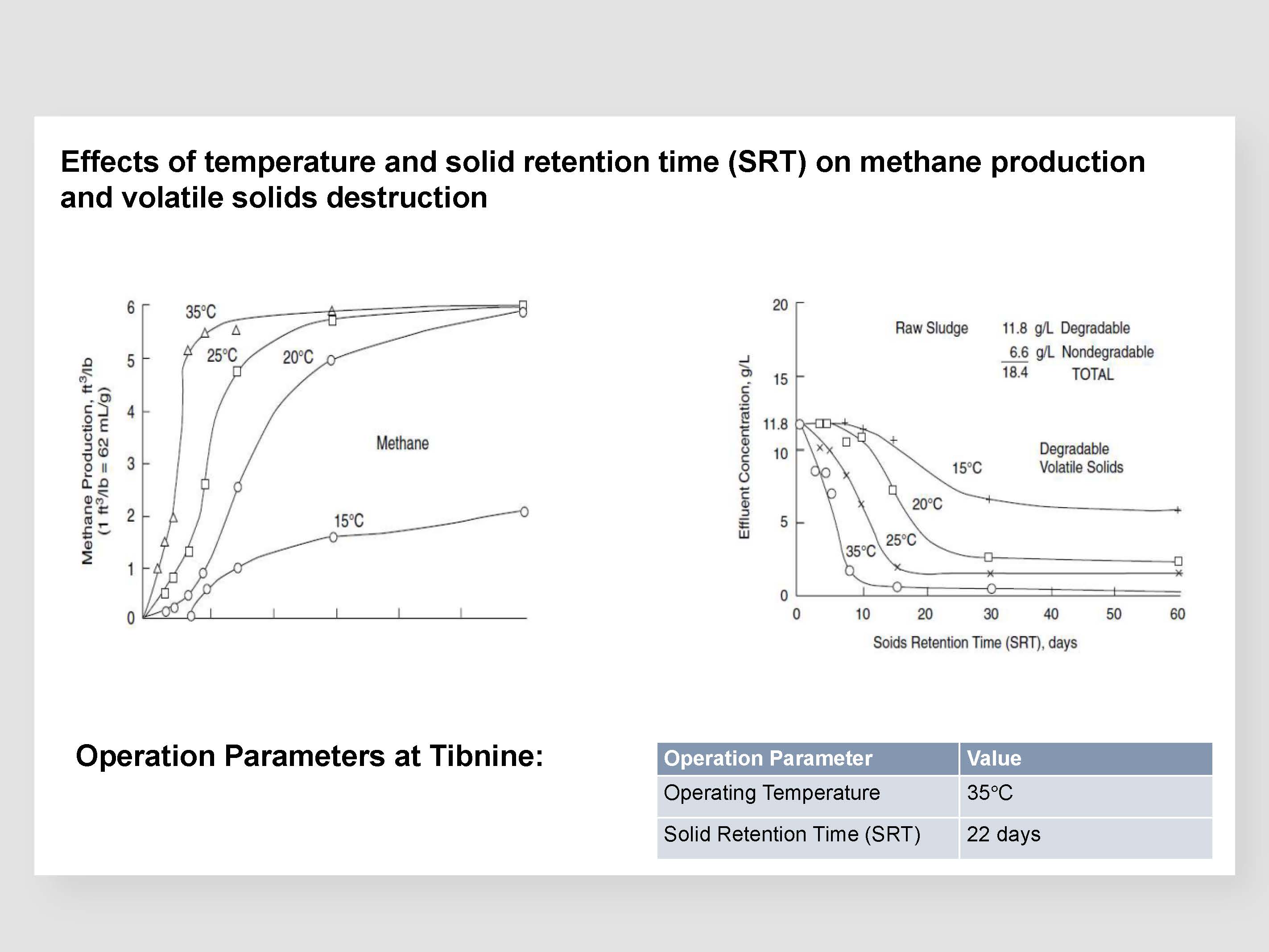

Performance of Anaerobic Digestion (Mesophilic Fermentation)

Performance Improvements For efficient anaerobic digestion, the process must be in steady-state and optimum operating conditions. The optimum operating temperature for mesophilic fermentation ranges between 30°C and 38°C. However, sharp and frequent temperature fluctuations affect the microorganisms. These can occur at temperature changes greater than 1°C/d. Therefore, the operating temperature in the digester has to be kept constant. Further, the microorganisms require sufficient time to reproduce and metabolize the volatile solids (compare figure), expressed as solid retention time (SRT). In the case study, the students selected a solid retention time of 22 days and an operating temperature of 35°C.

Energy Yield

El Joauhari et al. (2021)

El Joauhari et al. (2021)

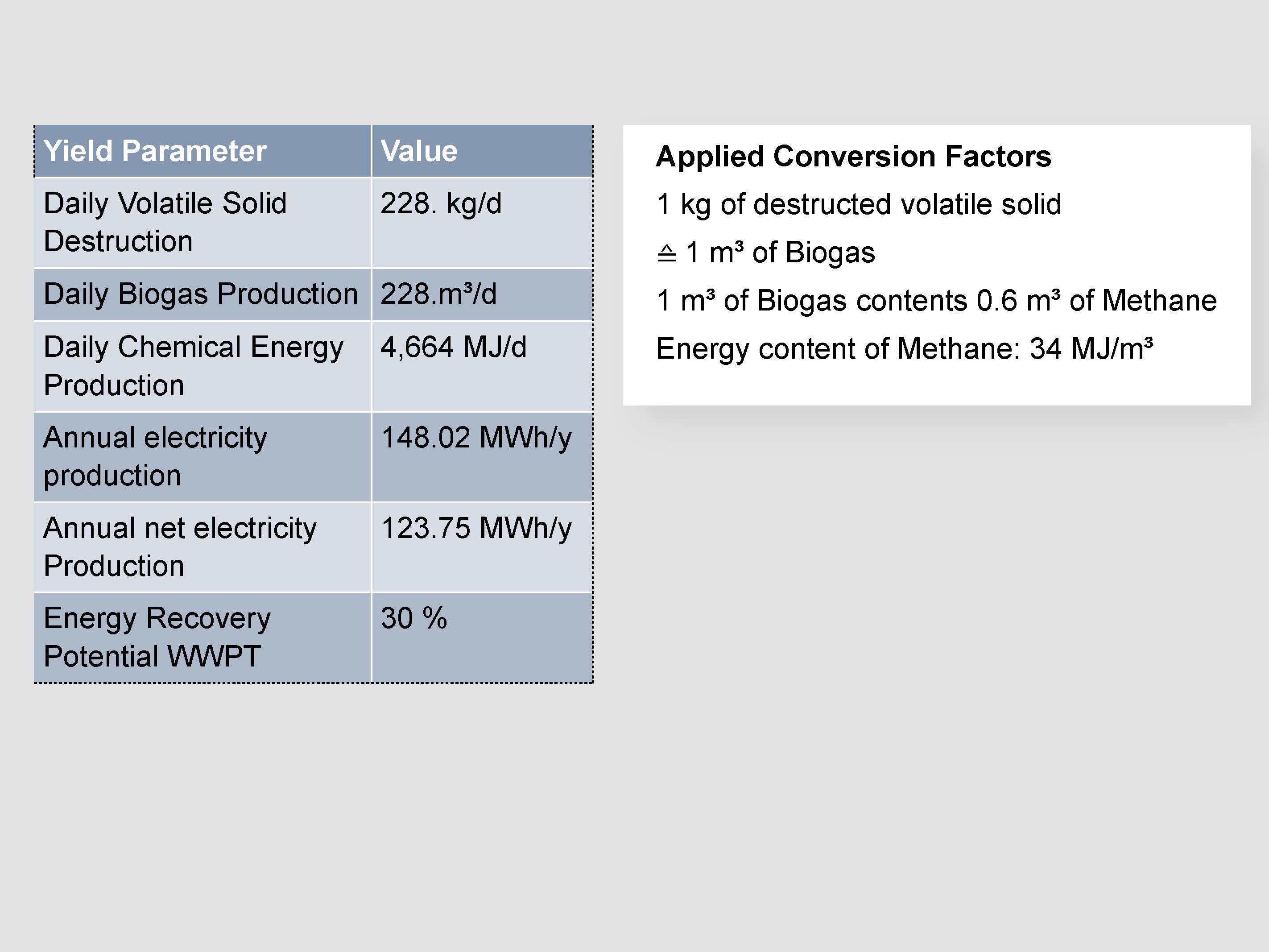

Energy Yield The mesophilic, anaerobic digestion is estimated to reduce the volatile solid by 61.25 %, corresponding to volatile solid destruction of 228. Kg/day. Specific gas production for volatile solids from wastewater sludge is assumed to be 1 m³/kg. This results in daily biogas production of 228.62 m³/d. Assuming a methane content of 60%, the daily methane production is 137.17 m³/d. With methane having a heating value of 34MJ/m³, the daily chemical energy generation sums up to 4,664 MJ/d. The electrical energy production 𝐸_𝑒𝑙 calculates as the difference between chemical energy generated 𝐸_(𝑐,𝑡) and chemical energy consumed for heating 𝐸_(𝑐, ℎ)multiplied by the biogas engine efficiency µ_𝑏𝑒:

- 𝐸_𝑒𝑙=(𝐸_(𝑐,𝑡)−𝐸_(𝑐,ℎ) )∗µ_𝑏𝑒

- 𝐸_𝑒𝑙=(4664 𝑀𝐽/𝑑−492.67 𝑀𝐽/𝑑)∗0.35∗(365/3600 𝑀𝑊ℎ)/𝑦∗𝑑/𝑀𝐽

- 𝐸_𝑒𝑙=148.02 𝑀𝑊ℎ/𝑦

Subtracting the annual electricity demand for the mixing unit (0.16 MWh/y) and the water pump (24.12 MWh), the annual net electricity production is 123.75 MWh/y. Given the total electricity demand of the WWTP of 412 MWh/y, the resulting energy recovery potential is 30.0%.

Next solution: Constructed Wetlands

References

Achinas, Spyridon; Achinas, Vasileios; Euverink, Gerrit Jan Willem (2017): A Technological Overview of Biogas Production from Biowaste. In Engineering 3 (3), pp. 299–307. DOI: 10.1016/J.ENG.2017.03.002

Ahmad, A., McCulloch, N., Al-Masri, M., & Ayoub, M. (2020). From dysfunctional to functional corruption: the politics of reform in lebanon’s electricity sector. ACE SOAS Consortium. https://www.aub.edu.lb/ifi/Documents/publications/working_papers/2020-2021/20201218_from_dysfunctional_to_functional_corruption_working_paper.pdf

BP (2021): Statistical Review of World Energy 2021. Available at https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-full-report.pdfm, last checked 23.11.2021

Deublein, D.; Steinhauser, A. (2008): Biogas from Waste and Renewable Resources. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA

El Joauhari, A., Nassreddine, C., Mgharbel, M., & Izmerly, Y. (2021). Renewable energy production from wastewater sludge in lebanon [Final Year Project]. Beirut Arab University. IRENA. (2016). Measuring Small-scale Biogas Capacity and Production. https://www.irena.org/publications/2016/Dec/Measuring-small-scale-biogas-capacity-and-production

Fachverband Biogas; GIZ. (2019): Biowaste to Biogas. Freising. Available online at https://www.energigas.se/library/2887/booklet-biowaste-to-biogas.pdf, checked on 11/8/2021.

Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe (2021): Basisdaten Bioenergie Deutschland 2021. Available at https://www.fnr.de/fileadmin/Projekte/2020/Mediathek/broschuere_basisdaten_bioenergie_2020_web.pdf; last checked on 23.11.2021

FAO. Water scarcity. http://www.fao.org/land-water/water/water-scarcity/en/

Gelaro, R., McCarty, W., Suárez, M. J., Todling, R., Molod, A., Takacs, L., Randles, C. A., Darmenov, A., Bosilovich, M. G., Reichle, R., Wargan, K., Coy, L., Cullather, R., Draper, C., Akella, S., Buchard, V., Conaty, A., da Silva, A. M., Gu, W., . . . Zhao, B. (2017). The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (merra-2). Journal of Climate, 30(14), 5419–5454. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1

IEA (2020): Outlook for biogas and biomethane. Prospects for organic growth. World Energy Outlook Special Report. Available at https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/03aeb10c-c38c-4d10-bcec-de92e9ab815f/Outlook_for_biogas_and_biomethane.pdf, last checked 23.11.2021.

Jaafar, H., Ahmad, F., Holtmeier, L., & King-Okumu, C. (2019). Refugees, water balance, and water stress: Lessons learned from lebanon. Ambio. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01272-0

Jaafar, H. (2021, May 10). Geospatial Environmental Assessment of Refugees impact on Host Communities: examples from the Syria - Lebanon case (CERN Cyberseminar on Refugee and internally displaced populations, environmental impacts and climate risks). American Universtiy of Beirut. https://www.populationenvironmentresearch.org/pern_files/statements/Geospatial Environmental Assessment of Refugees impact on Host Communities_Jaafar.pdf

Kaltschmitt, Martin; Hartmann, Hans; Hofbauer, Hermann (Eds.) (2009): Energie aus Biomasse. Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren. 2. Aufl. 2009. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Available online at http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:31-epflicht-1526232.

Kaza, Silpa; Yao, Lisa; Bhada-Tata, Perinaz; van Woerden, Frank (2018): What A Waste 2.0. A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. Washington: World Bank Group (Urban Development). Available online at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30317.

Müller, C. (2007), „Anaerobic Digestion of Biodegradable Solid Waste in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Overview over existing technologies and relevant case studies“, Eawag Sandec, available online at https://sswm.info/sites/default/files/reference_attachments/MUELLER 2007 Anaerobic Digestion of Biodegradable Solid Waste in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.pdf, last checked on 08.11.2021

Murphy, J.; Weiland, P.; Braun R.; Wellinger, A. (2011): Biogas from Crop Digestion. Edited by IEA Bioenergy

Pfeinninger, S., & Staffell, I. Renewables.Ninja. https://www.renewables.ninja/

Statistisches Bundesamt (2021): Bodenfläche insgesamt nach Nutzungsarten in Deutschland; available at https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Landwirtschaft-Forstwirtschaft-Fischerei/Flaechennutzung/Tabellen/bodenflaeche-insgesamt.html; checked on 23.11.2021

Stolze, Y., Zakrzewski, M., Maus, I. et al. Comparative metagenomics of biogas-producing microbial communities from production-scale biogas plants operating under wet or dry fermentation conditions. Biotechnol Biofuels 8, 14 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-014-0193-8

Vögeli, Y.; Lohri, C. R.; Gallardo, A.; Diener, S.; Zurbrügg, C. (2014): Anaerobic digestion of biowaste in developing countries. Practical information and case studies. Dübendorf, Switzerland

World Biogas Association (2019): Global Potential of Biogas, available online at https://www.worldbiogasassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/WBA-globalreport-56ppa4_digital.pdf, last checked on 08.11.2021