1.3 Beyond the basic Nexus framework

- The “WEF Nexus” concept is not restricted to water, energy and Food and invites to incorporate other components

- Each Nexus system depends on an individual composite of varying components

- As every region is unique in terms of resources availability and use, we need to adapt the concept to address the case-specific challenges

1.3.1 Global Resource Nexus

- five resources: water, energy, minerals, food and land

Source: Global Resource Nexus after Andrews-Speed et al. 2012.

Andrews-Speed et al. 2012 conceptualize a nexus focusing on five key resources: water, energy, minerals, food, and land. The Global resource nexus analyzes physical, technological, social and institutional aspects of sectoral interactions.

A key claim of the approach is that one needs to understand the key actor‘s decision-making processes over resource management. Thus, the global resource nexus approach requires a closer look at supply chains of companies, the strategic planning of politicians or public administrations, and the basic needs of local populations.

1.3.2 Water-Energy-Food-Soil (WEFS) Nexus

Adding soil as component

Source: WEFS-Nexus after Hatfield et al. 2017.

Hatfield et al. 2017 put an emphasis on soil as important element of the water, food, energy nexus.

Soil resources are essential for food supplies, a crucial sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide, and an integral part of ecosystems. However, WEF-nexus studies rarely integrate soils as a key research component even though there are many links to the WEF-nexus: Soils support various ecosystem services such as nutrient transformation, nutrient availability, water quality, water renewability, transport of pollutants, and groundwater table fluctuations. Soils also enable the production of biomass. Biomass, in turn, can be used for food, feeding, fiber, and biofuels (Lal et al., 2017).

The lack of awareness about soils translates into a lack of solutions and actions that improve soil management (Hatfield et al. 2017; Gu et al., 2021). Unsustainable soil management and pollution (i.e., agriculture, waste management) profoundly affect soil processes and change soil properties. For instance, soil erosion and degradation lead to declining soil productivity and thus cause declining yields. Hence, preventative measures to achieve soil health for food security and ecosystem health are crucial (Hatfield et al. 2017; Gu et al., 2021).

1.3.3 WEF Nexus: The Environmental Livelihood Security (ELS)

Source: WEF-Nexus and Environmental Livelihood Security after Biggs et al. 2015.

Biggs et al. (2015) put livelihoods in the center of the WEF Nexus circle: the Environmental Livelihood Security (ELS). ELS refers to the “challenges of maintaining global food security and universal access to freshwater and energy to sustain livelihoods and promote inclusive economic growth, whilst sustaining key environmental systems functionality, particularly under variable climatic regimes’’ (Biggs et al., 2014). This concept also considers external influencing factors such as climate change, population growth, and governance, which all affect the attainment of ELS.

After evaluating different Nexus approaches to improve the understanding about the interrelated dynamics between human populations and the natural environment, they present an integrated framework with the capacity to measure and monitor environmental livelihood security of whole systems by accounting for the water, energy and food requisites for livelihoods at multiple spatial scales and institutional levels

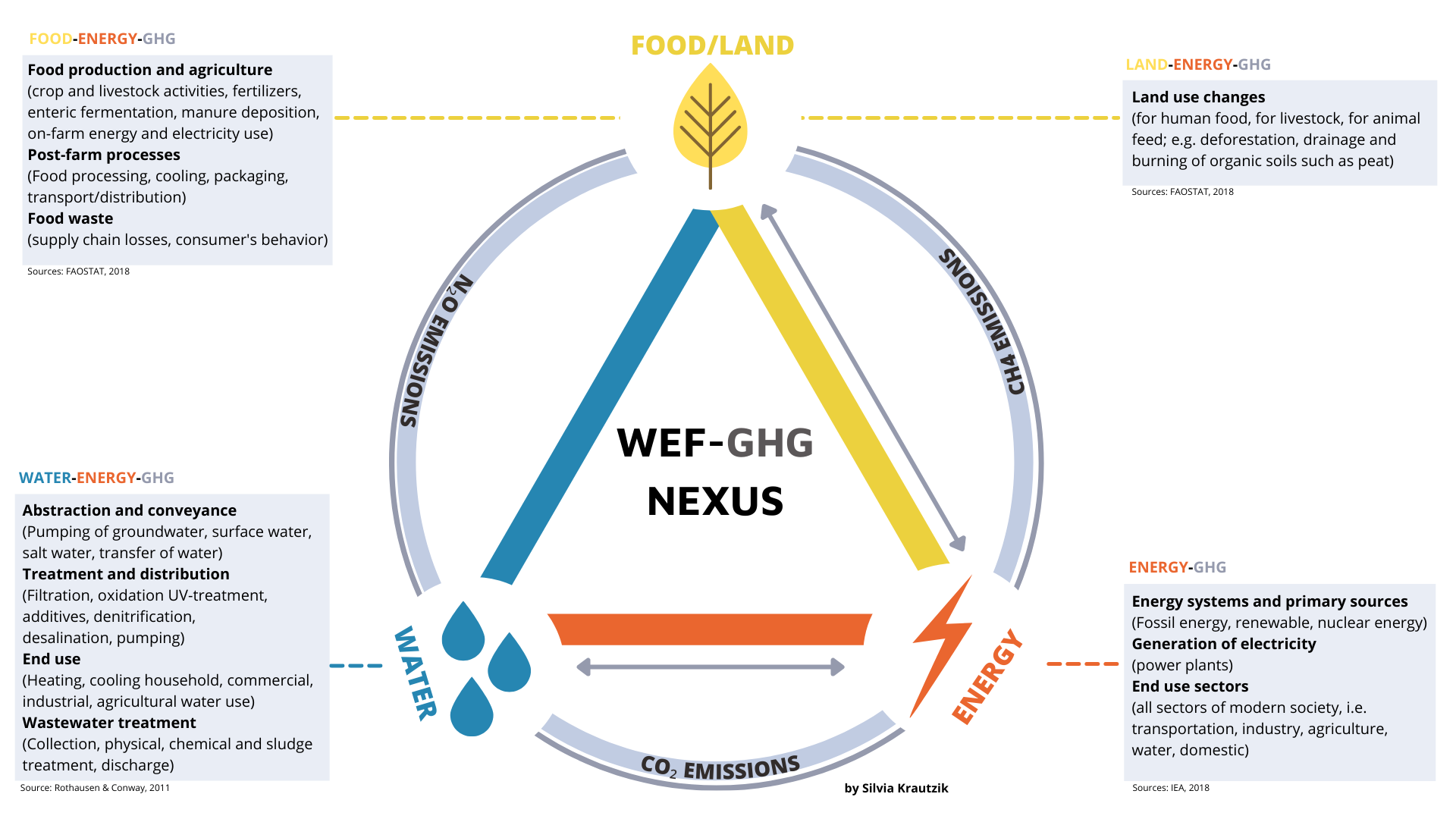

1.3.4 Greenhouse gases (GHGs) and the WEF-Nexus

Integrating aspects of global warming into the WEF-Nexus

In the light of global warming, it is important to keep in mind that all three sectors (WEF) are key emitters of GHGs. A nexus analysis can be used to determine the sources of GHG emissions within the different components of a system. More importantly, trade-offs or synergies can be identified through the nexus lens:

Trade-offs may exist between GHG reduction and resource security and a comprehensive nexus assessment can provide the insight needed into these trade-offs. For example, nuclear power is commonly seen as a carbon-free alternative but at the same time, it is extremely water-intensive which then can compromise the water security of a region (IRENA, 2015). Another central question for a GHG-WEF-Nexus could be to identify how increasing demands for water, energy or food can be balanced with the need to reduce global GHG emissions.

Source: "Integrating GHG into nexus systems", Silvia Krautzik.

GHG emissions from the agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) sector

Crippa et al., 2021 estimate that the world‘s food systems are responsible for more than one-third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. The study is based on a new database for global food emissions called “EDGAR-FOOD”. The database estimates GHG emissions for the years 1990–2015. Several steps along food supply chains release GHGs and require energy, including farming, generation of fertilizers, harvesting (e.g., using machinery), transport, processing, packaging, distribution, preparation, and disposal of residuals.

GHG emissions from the food sector encompass CO2, CH4, N2O, and F-gases.

For example, carbon losses occur due to deforestation or the degradation of organic soils such as peatlands. Livestock production or waste treatment release CH4, and F-gases are linked to foodstuff refrigeration. Interlinkages between food-systems and GHG emissions are plentiful and center not only around CO2 emissions (Crippa et al., 2021).

CO2-Emissions from the water sector

Water supplies depend on energy. Running water pumps or treating wastewater are just a few examples that require energy and exemplify the water-energy nexus. In addition, the interactions within the water-energy sectors link the release of GHG, such as carbon dioxide to the nexus. For example, the water sector requires energy for the construction of wells, conveyance pipes, treatment plants, and the operation phase. Operational processes include energy consumption for maintaining the built water system (Rothausen & Conway, 2011).

However, Rothausen & Conway (2011) stress that links between the water and energy sector are not thoroughly studied, and the assessment of GHG from the water sector depends on the chosen boundaries for the water system itself. For example, end-use purposes such as residential water heating might be excluded from the assessment since this process occurs outside of the water sector.

References

1.3.1 Global Resource Nexus - five resources: water, energy, minerals, food and land

Andrews-Speed, P., R. Bleischwitz, G. Kemp, S. VanDeveer, T. Boersma and C. Johnson 2012. The Global Resource Nexus. The Struggles for Land, Energy, Food, Water and Minerals, 2012, Washington D.C., Transatlantic Academy.

1.3.2 Water-Energy-Food-Soil (WEFS) Nexus

Gu, B., Chen, D., Yang, Y., Vitousek, P., Zhu, Y. (2021): Soil-Food-Environment-Health Nexus for Sustainable Development, Research, Article ID 9804807, 2021. <a href=”https://doi.org/10.34133/2021/9804807”> https://doi.org/10.34133/2021/9804807</a>

Hatfield, J.L.; Sauer, T.J.; Cruse, R.M. (2017): Soil: The forgotten piece of the water, food, energy nexus. In: Advances in Agronomy, Vol.143: 1-46 . doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2017.02.001

Lal, R., Mohtar, R.H., Assi, A.T. et al. (2017): Soil as a Basic Nexus Tool: Soils at the Center of the Food–Energy–Water Nexus. Curr Sustainable Renewable Energy Rep 4, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40518-017-0082-4

1.3.3 WEF Nexus: The Environmental Livelihood Security (ELS)

Biggs, EM., Bruce, E., Boruff, B., Duncan, JMA., Horsley, J., Pauli, N., McNeill, K., Neef, A., Ogtrop, FV., Curnow, J., Haworth, B., Duce, S. & Imanari, Y. (2015), ‘Sustainable development and the water-energy-food nexus: A perspective on livelihoods’, Environmental Science and Policy, vol. 54, pp. 389–397.

1.3.4 Greenhouse gases (GHGs) and the WEF-Nexus

Crippa, M., Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Tubiello, F. N., & Leip, A. (2021). Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food, 2(3), 198–209. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9

FAO, (2018), Emissions due to agriculture. Global, regional and country trends 2000–2018, FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series No 18, Rome.

IEA, (2018), Global Energy & CO2 Status Report 2018, IEA, Paris, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-co2-status-report-2018 [accessed 12/30/2021]

IRENA, (2015), Renewable Energy in the Water, Energy & Food Nexus, https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2015/IRENA_Water_Energy_Food_Nexus_2015.pdf [accessed 12/30/2021]

Rothausen, S. G. S. A., & Conway, D., (2011), Greenhouse-gas emissions from energy use in the water sector, Nature Climate Change, 1(4), 210–219. doi:10.1038/nclimate1147

Additional Information:

EDGAR-FOOD database available at: https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/.