4.2 Challenges related to Food Security

4.2.1 Levels of undernourishment

The prevalence of undernourishment is defined as the “proportion of the population whose dietary energy consumption is less than a pre-determined threshold. This threshold is country specific and is measured in terms of the number of kilocalories required to conduct sedentary or light activities.” (FAO, 2008)

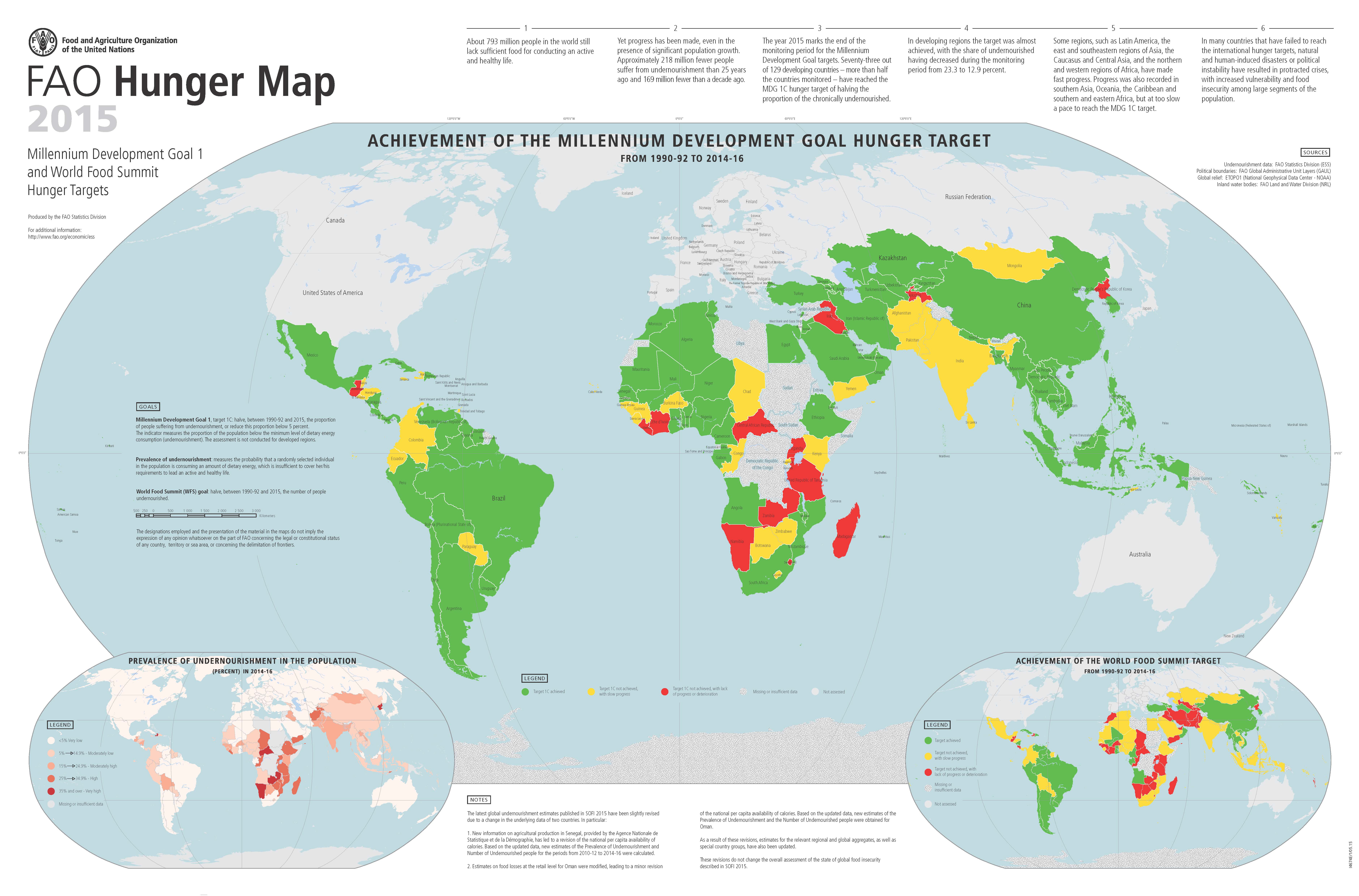

This map shows the percentage of the population in each country that is affected by undernourishment from 2014 to 2016. The lightest shade of red refers to 5-15% of the population being affected by undernourishment. In total, approximately 793 million people in the world still lack sufficient food for conducting an active and healthy life. Even though the MDG target to prevent undernourishment between 2000 and 2015 was achieved in many countries, it failed in others. Thus, more efforts are necessary to continue reducing the existing levels of undernourishment.

In addition to systematic development challenges, natural and human-induced disasters and political instability have contributed to protracted crises, and have increased vulnerability and food insecurity among large sections of the population.

4.2.2 Net food trade (in 2020)

FAO, 2020.

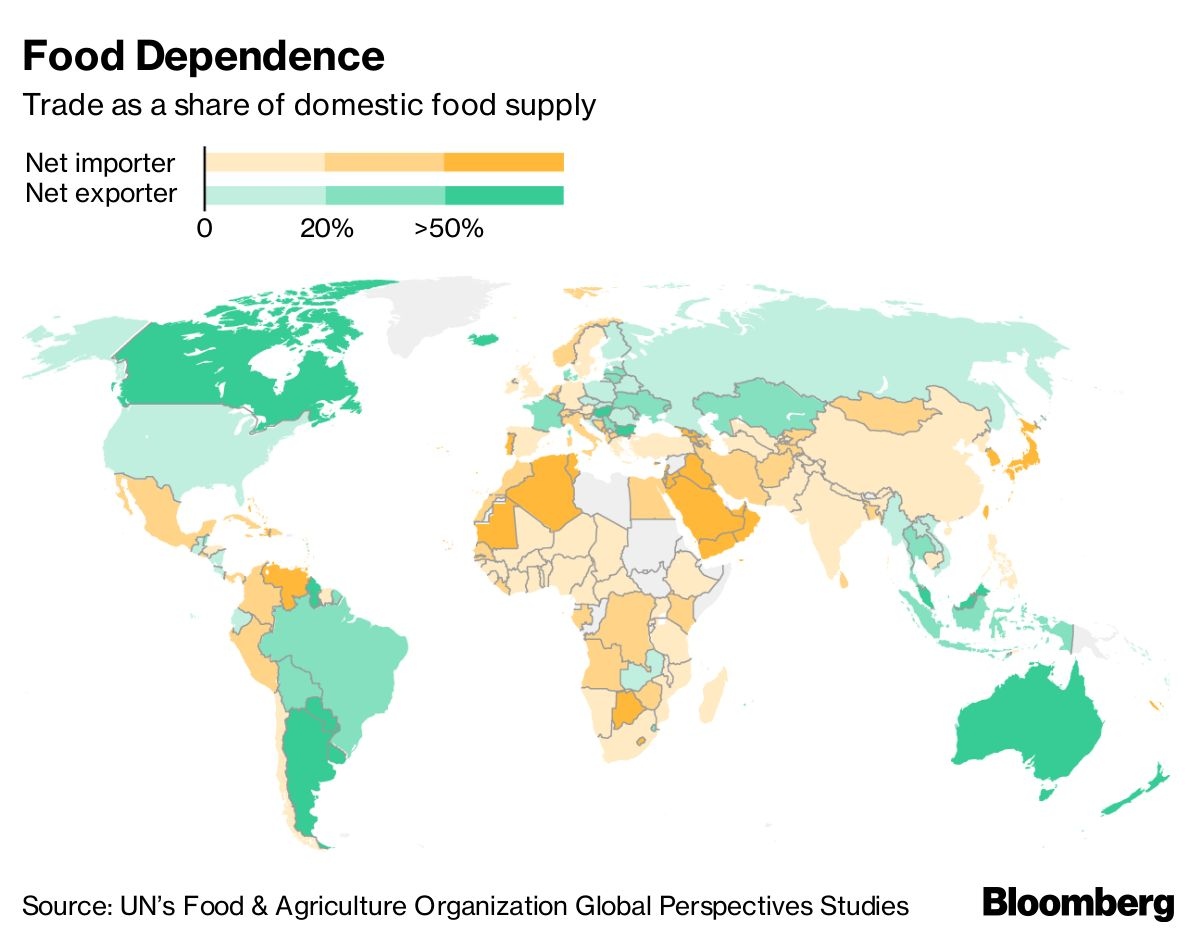

Net food trade is defined as the net difference between food exports and food imports, presented as a percentage of the total food consumption within that country.

The main countries being food exporters are USA, Canada, Ukraine, Argentina and Australia and some South American and South East Asian economies. The most striking pattern in the map is the reliance of the entire African continent on food imports, especially the North African region. The other notable pattern is the reliance of both China and India have on food imports despite the scale of their own domestic agricultural output.

4.2.3 Bren D´Amour and Anderson, 2020: International trade and the stability of food supplies in the Global South

Christopher Bren d’Amour and Weston Anderson 2020.

The importance of food imports across the Global South has increased since 1960 (figure 1). Countries in Africa (figures 1(b) and (c), red line), in particular, import a much larger share of their rice and wheat supplies.

Importantly, the figure above only depicts countries whose caloric dependency ratio exceeds 10%, i.e. countries that get at least 10% of the total calorie supply through the specific crop. For wheat, average import dependency ratios (IDR) in Africa almost doubled from 1960 to 2013, from about 0.25 to almost 0.5. These numbers are not problematic per se; however, they indicate an increasing reliance on imported staple crops of countries in the Global South and potentially problematic exposure, for example to teleconnected food supply shocks (Bren d’Amour et al 2016).

4.2.4 World agricultural production

When it comes to the world agricultural production it can be relevant and interesting to ask questions such as:

- Why does food production experience spikes of growth and decline?

- What has enabled Asia to increase its food production by so much?

- Why has European food production fallen since the 1980s?

- In contrast, why has US food production increased over the whole time period?

- Finally, and very importantly, why has African food production declined over the 40 year period despite independence, development and billions of dollars of multilateral aid support?

4.2.5 Yield gap for major cereals

Mueller et al., 2012.

The yield gap refers to the difference between two levels of yield. On this section, these two levels are the observed yields and the attainable yields (the best yield achieved through skilful use of the best available technology) for maize, wheat and rice. The yield gaps are presented as a percentage of the attainable yield. (Mueller et al., 2012; FAO, 2015).

This figure shows the yield gap for major cereals at a global scale. In parts of Africa, achieved yields are a mere 10% of the attainable yield. The values for USA, Canada, Western Europe and some parts of China and India are typically > 80%. The situation in Central Europe, Latin America and Central Asia is mixed and varies widely.

Overall, this figure shows that many regions in the world are still far from approaching attainable yield. Increasing yields are possible through agricultural management practices such as water and nutrient provision and disease control.

4.2.6 Contribution of family and smallholder farming to National and Global Food Security

FAO, 2014

Smallholder farming - often on less than 1 ha property - is estimated to account for 70-90% to global food production. It keeps food production and consumption at the local scale and avoids external dependencies, preserves traditional food products, maintains global agro-biodiversity, provides an important source of income and employment, and thus contributes to social stability and promotes the sustainable use of natural resources. Family and smallholder farming is therefore considered as a key activity in eradicating global food insecurity.

In order to support family farming in poor countries, the following strategies are recommended:

- On-farm investments for increasing productivity and developing resilience

- Collective investments in productive assets

- Investing in risk management strategies

- Improving smallholders’ access to input markets

- Investing to develop markets that favour smallholders

- Increasing smallholders’ access to financial services

- Investing in enabling institutions for social protection, tenure protection, etc.

4.2.7 Smallholder farming - global breakdown of holding sizes

HLPE, 2013

This graph presents the breakdown of farmland areas held by different parties from an 81 country global subset, and divided according to world region. Note that the y-axis is a measure of the total plots of land, not the total land area occupied for farming.

80% of the farmland in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia is managed by smallholders (defined as an area of up to 10 hectares). There are 450 million smallholder farmers in the developing world, and 73% of the holdings are land areas of less than 1 ha. Smallholder agriculture is the foundation for food security in many countries and an important part of the socio/economic/ecological landscape in all countries. Strengthening the resilience of smallholder agriculture to climate change impacts is an important step towards eradicating global poverty.

Income is important for smallholders’ access to food, manufactured goods and services of all kinds. The value of the production per hectare is therefore an important parameter, especially when exploitations are “small”. The intensity of employment is also an important contributing factor, as smallholder agriculture is labour-intensive.

4.2.8 Approximately one-third of global food is wasted

Oxfam Australia, 2012

This section emphasises the problem of food waste. Next to large scale crop failure and destruction of harvest on the field contributing to the yield gap, post-harvest losses are often very significant! It is estimated that worldwide approximately 1/3 of global food production is wasted. In developing countries this is often due to a lack of storage, transport and refrigeration. In industrial countries it is often because retailers and consumers are actually throwing away food.

4.2.9 Global impacts: COVID-19 outbreak

UN, 2021

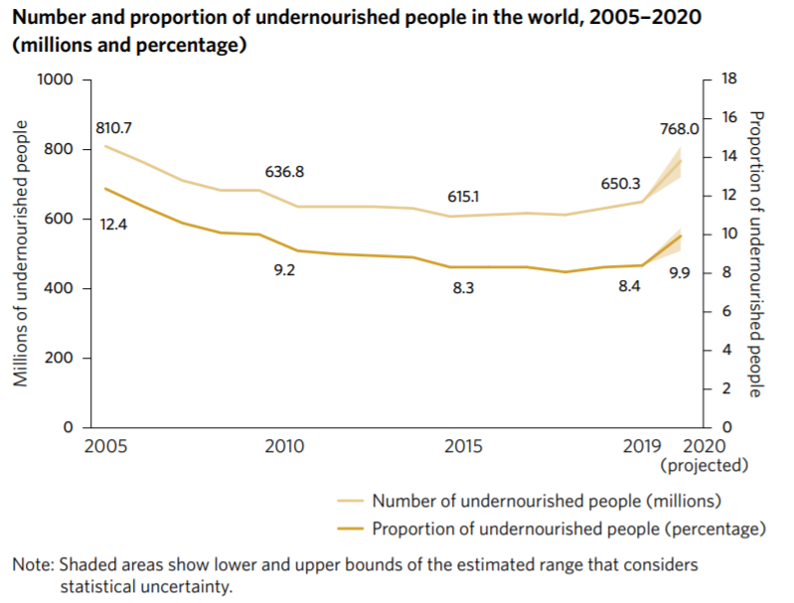

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted every aspect of life, including the food security and nutrition status of millions of people across the globe. However, the number of undernourished people in the world was on the rise since 2014, long before the COVID-19 outbreak: Around 650 Million people suffered from undernourishment and 2 billion people experienced food insecurity in 2019 during pre-pandemic times.

(The figure above shows that around 650 million people suffered from undernourishment in 2019- that is around 8.4% of the global population).

On top of that, the COVID-19 outbreak exacerbated hunger worldwide. According to the UN’s Sustainable Development Report from 2021, an additional 70 to 161 million people experienced hunger as a result of the pandemic. The total number of undernourished people might rise as high as 768 million people (see also figure above).

Key effects of COVID-19 on food system include the disruption of food supply chains, creation of unexpected stress on food systems increased social inequalities, and losses of income. It is important to mention that one of the main risks to people’s food security was not created by disruptions along supply chains, but from COVID-19s direct impacts on employment and livelihoods.

In 2020, around 2.37 billion were affected by moderate or severe food insecurity- that is an increase of 320 million people compared to 2019. This increase means that more people became unable to eat a healthy, balanced diet on a regular basis, they had less food or even worse, some people might have gone without anything to eat. The financial impacts were particularly higher for women. Moderate or severe food insecurity is 10 % higher among women than men for the year 2020, compared to 6 % in 2019.

For instance, around 30% of women of reproductive age (aged 15 to 49 years that is) are globally affected by anaemia due to nutritional deficiencies in 2019. There are significant variations on a regional scale, with more than 30% of women in Africa and Asia being affected by anaemia, and only 14.6 percent of women in Northern America and Europe.

It is also expected that the pandemic will worsen child malnutrition. In 2020, around 22 % of children under age 5 suffered from stunting. During the same year, wasting affected around 6.7 % children under age 5 and overweight affected 5.7%. Important to mention is that these estimates from 2020 are at alarming levels but do not reflect the impact of the pandemic yet. Impacts on household wealth, and changes in availability and affordability of nutritious food and essential nutrition services will show their impacts on children’s malnutrition in the next years.

In sum, the COVID‑19 outbreak will push global rates of hunger and food insecurity even higher in the next years to come.

References

4.2.6 Contribution of family and smallholder farming to National and Global Food Security

- FAO (2014), ‘Family Farmers: Feeding the world, caring for the earth’, Available from: http://www.fao.org/docrep/019/mj760e/mj760e.pdf

- HLPE (2013), ‘Investing in smallholder agriculture for food security. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome, Available from: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/hlpe/hlpe_documents/HLPE_Reports/HLPE-Report-6_Investing_in_smallholder_agriculture.pdf

5.2.7 Smallholder farming

- HLPE (2013), ‘Investing in smallholder agriculture for food security. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome, from:http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/hlpe/hlpe_documents/HLPE_Reports/HLPE-Report-6_Investing_in_smallholder_agriculture.pdf

- FAO (2016), ‘The State of Food and Agriculture’, Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6132e.pdf

4.2.8 Approximately one-third of global food is wasted

- Oxfam Australia (2012), ‘What’s wrong with our food system?’, Available at: https://www.oxfam.org.au/2012/05/whats-wrong-with-our-food-system/

4.2.9 Global impacts: COVID-19 outbreak

-

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2021. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Rome, FAO.

-

OECD. 2021. COVID-19 and food systems: Short- and long-term impacts. OECD Food. Agriculture and Fisheries Papers. No. 166. OECD Publishing, [Paris]: https://doi.org/10.1787/69ed37bd-en.

-

United Nations. 2021. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. [Online] https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf

-

WHO. 2021. Anaemia. [Online] https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia#tab=tab_1