7.3.3 Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) as Nexus integrated solution

What is Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR)?

Managed aquifer recharge (MAR) is a technique used to recharge water to aquifers intentionally. Put simply, one can say that MAR is a practice that increases the amount of water that enters a groundwater reservoir. Managed groundwater recharge is done by storing water in basins, furrows, or other structures that allow surface water to infiltrate into the soil and recharge aquifers (Bouwer et al., 2002).

Example of infiltration basins (Source:); Take a look at the Shafdan site in Israel here.

The picture from the link shows the Shafdan wastewater treatment plant South of Tel Aviv, Israel. However, the Shafdan site is more than just a treatmeant plant: The Shafdan site is a full-scale water reuse scheme, including artificial managed aquifer recharge. The operators of Shafdan infiltrate secondary treated effluent into aquifers via large basins. You can see these basins on the picture, some of them are already filled with water. The infiltrated water is re-abstracted from the aquifers after a time period of 6-12 months and used for irrigation (AquaNes, 2016).

Terminology

Note that sometime the terms „enhanced recharge”, “water banking”, and “sustainable underground storage” are used to refer to MAR. More importantly, Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) is also referred to as „artifical aquifer recharge“. The latter has been replaced by „MAR“ because of the negative connotation of the word „artificial“. It somewhat implied that the water was unnatural when in fact, MAR is based on natural processes. One key reason the new terminology of MAR was the involvement of society in water resources management. As community participation becomes more important, the term „artificial aquifer recharge“ might be misleading (Dillon, 2005).

Categories of aquifer recharge

MAR can happen intentionally or unintentionally. Depending on several human activities that enhance aquifer recharge, three categories are considered:

- Unintentional recharge: Recharge might happen due to land clearing, irrigated areas, or based on leaks from storm water drains, and sewers in urban areas.

- Unmanaged recharge: Recharge occurs due to storm water drainage wells. The intention behind this activities is the disposal of the water withouth further reuse. Another example would be septic tanks that leach fields.

- Managed recharge: Recharge happens through built and planned recharge structures. These recharge structures are designed for water recovery and for storage of water to provide environmental benefits (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC, 2009; Page et al., 2018). For instance, the infiltration basins at the Shafdan wastewater treatment plant fall under this category.

Overview of MAR schemes

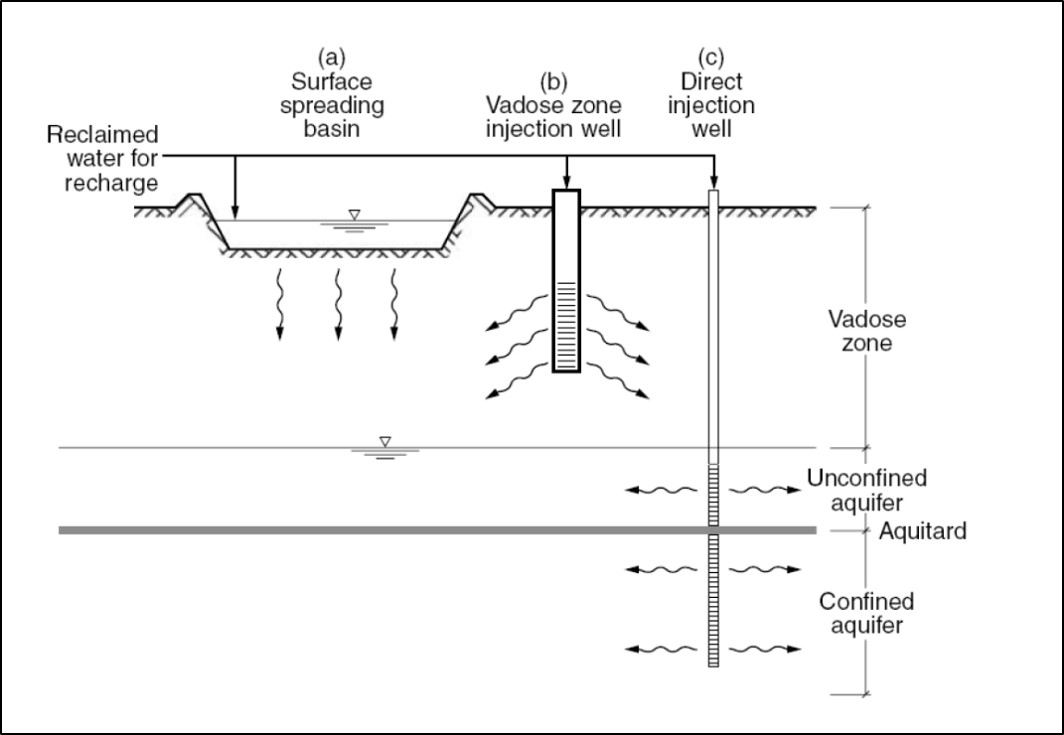

A wide range of methods and technical designs are available for recharging water into the ground. The MAR technologies range from low-tech to more advanced ones. Hence, it is better to understand “MAR” as an umbrella term for different kind of recharge methods. The different methods depend on different conditions such as hydrogeological conditions, aquifer characteristics, and water quality (Page et al. 2018). The figure above shows the implementation of MAR for different scenarios.

NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009. Notes: reclaimed water = term for treated sewage/recycled water; Confined aquifers might require different MAR schemes than unconfinded aquifers

NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009. Notes: reclaimed water = term for treated sewage/recycled water; Confined aquifers might require different MAR schemes than unconfinded aquifers

(a) Surface Spreading System/Infiltration Basins are a simple method of MAR. Different kinds of water such as stormwater, river water or treated wastewater are stored on the land surface or impounded in infiltration basins or modified stream channels. Usually the water table is below the land surface and the water from the basin infiltrates through the unsaturated zone. Surface Spreading basins are often used to recharge shallow unconfined aquifers (Maliva, 2019).

(b) Vadose zone injection wells (VZW) are also called dry wells or recharge shafts. VZWs are shallow wells that are commonly used when groundwater tables are relatively deep. This technique is particularly relevant when implementing MAR schemes in semiarid or arid regions where groundwater tables very deep (i.e. 100 to 300m or more). Additionally, VZWs are preferred on sites where permeable soils are not available. The VZWs allow infiltration of water through the unsaturated zone to unconfined aquifers at deeper levels (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC, 2009; Liang, et al., 2018). Infiltrating water through the vadose zone offers a range of benefits. For instance, the water infiltration might lead to improved water quality via biological, chemical and physical processes before reaching the aquifer (Liang, et al., 2018).

(c) Direct Injection Wells are widely used across the globe. This method injects water into an aquifer where the water is stored over a defined period. The storage period is followed by a period of water recovery. This means that the aquifer’s recharged water is pumped from the same well for further use (Casanova, 2016). In general, this method is suitable to recharge confined as well as unconfined aquifers (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC, 2009).

7 key elements of MAR schemes

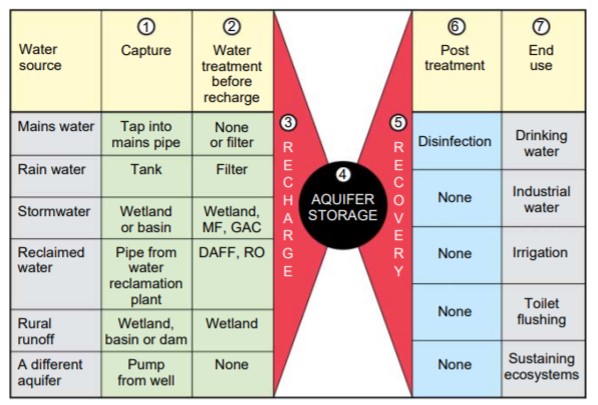

Source: Dillon et al., 2010

How does MAR work in detail? MAR describes different recharge techniques that allow reclaimed water to infiltrate into aquifers for groundwater recovery or other environmental benefit (Sprenger et al., 2017; Page et al., 2018; Salameh et al., 2019). The figure above shows typical sources of water and the methods of capture, pre-treatment and post-treatment of water for managed aquifer recharge. The circled numbers in the figure show the seven common elements of a managed aquifer recharge system: (1) water capture, (2) pre-treatment, (3) recharge, (4) storage, (5) recovery, (6) posttreatment, and (7) end use (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC 2009; Dillon et al., 2010).

Example: Soil aquifer treatment (SAT)

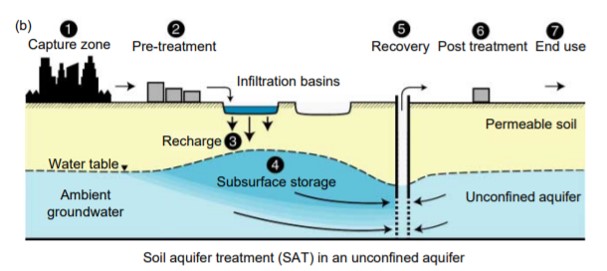

Source: NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009

A more detailed example showing the 7 key elements or MAR schemes can be found in this section. The figure above shows a MAR system known as soil aquifer treatment (SAT) that infiltrates water into an unconfined aquifer. SAT is often used to enter stormwater or pre-treated wastewater (2) through an infiltration basin. As the sewage effluent moves through the soil and aquifer, nutrient and pathogen removal is facilitated and the quality of the effluent improves. The water is then stored in the underlying aquifer (3-4). The water can now be reused (5) for different purposes such as irrigation, industrial use, drinking water or discharge into ecosystems. Depending on the end-use the water will require post-treatment (6) before it is distributed to its users (NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009; Dillon et al., 2010).

SAT is just one of man MAR methods. Other types of MAR systems are listed below (NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009):

- Aquifer storage and recovery (ASR)

- Aquifer storage, transport and recovery (ASTR)

- Vadose zone wells

- Percolation tanks and recharge weirs

- Rainwater harvesting

- Bank filtration

- Infiltration galleries

- Dune filtration

- Infiltration ponds

- Soil aquifer treatment

- Underground dams

- Sand dams

- Recharge releases

Site-specific examples: MAR Portal

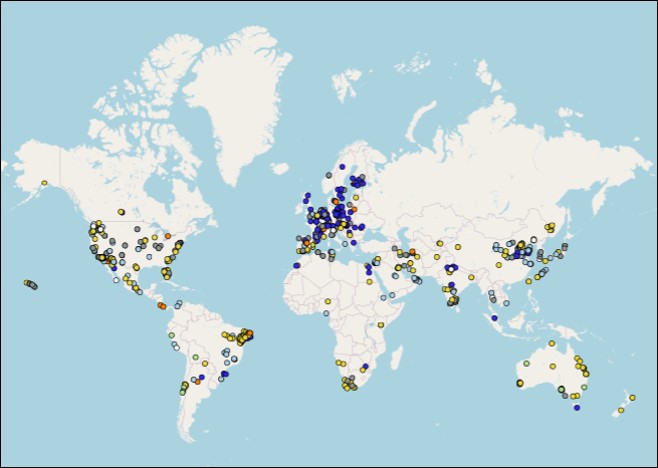

Source: Stefan & Ansem, 2017/ MAR Portal

Site-specific selection of recharge methods

The selection of recharge methods highly depends on the geographical context and site-specific conditions in the study region (NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009; Sprenger et al., 2017). Additionally, configuration and size of a recharge method also depends on factors like land availability, costs, compatibility with other land uses, required infiltrations rates or the thickness of the low-permeability layer (NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009; Salameh et al., 2019). Take for example the application of a MAR system in urban areas. Land is usually expensive in urban areas and a land efficient recharge method should be selected (NRMMC–EPHC –NHMRC, 2009).

Many different MAR case studies across the globe are available. The global MAR inventory lists over 1,200 case studies from over 50 countries from Europe, Asia, Africa, North and South America, and Oceania. The map above shows site-specific examples from the MAR portal listed by main objective of the MAR projects. Link: https://www.un-igrac.org/special-project/mar-portal

Benefits of MAR

When to use MAR?

Groundwater overexploitation has rapidly increased over the past decades due to electricity distribution for water pumping, population growth in urban areas, and the need for increased food production. In the first place, MAR is a solution that can enhance the quantity and quality of groundwater in different regions (Dillon et al., 2018). At the same time, MAR offers additional benefits.

What are the benefits of MAR?

-

Flood risk management: Floodwater can be used for recharge and combined with surface storage to dampen the flood peak.

-

Salt-water intrusion prevention: MAR can stabilize or recover ground water levels in overexploited aquifers. Replenishment of coastal aquifers can provide additional water supply while preventing saltwater intrusion. One successful example is the MAR scheme in the Burdekin Delta. Groundwater resources in the Delta are located at shallow depths and the groundwater itself is used for sugar cane and crop production. MAR is used to maintain high watertables which prevent the saltwater to migrate further inland (Charlesworth et al., 2002).

-

Aquatic ecosystem restoration: MAR can benefit aquatic ecosystem restoration whenever stored groundwater is discharged to help maintain environmental flows requirements.

-

Droughts: MAR can help build drought resilience by providing a storage for multiyear droughts without losses due to evaporation

-

Multi-purpose projects: MAR can be integrated in urban water projects, combining wastewater reuse or wetland restoration.

Challenges

Serrano-Tovar et al. (2019)

Serrano-Tovar et al. (2019)

-

Clogging is one of the most common and severe issues when operating a MAR scheme. Clogging means that the permeability of a porous medium is reduced. As a result, clogging causes a decrease in the recharge rate (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC, 2009). For example, in a Soil Aquifer Treatment (SAT) system, a clogging layer could create waterlogged conditions for nearby crops (Grinshpan et al., 2021).

-

Mismanagement of MAR schemes related to the infiltration of source water with poor quality can create high risks for public health and the environment. Hence, operational monitoring of hazards in a MAR scheme is essential for managing human and environmental health risks (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC, 2009).3)

-

MAR schemes require monitoring. However, monitoring can become a barrier for small-scale projects since it imposes high costs. Moreover, in some cases, water quality monitoring might not work due to the lack of sampling equipment or nearby laboratories (Page et al., 2020).4)

-

When implementing MAR, groundwater allocation plans and groundwater entitlements have to be considered to avoid potential use conflicts (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC, 2009).5)

-

Policies and local guidelines are required to ensure that MAR does not threaten human and environmental health. However, these kinds of policies are still lacking in many countries. The Australian national guidelines for MAR are the only national guidelines that align with the WHO’s water safety plan approach and govern the protection of human environmental health. Besides, a lack of regulatory frameworks also causes uncertainty when implementing MAR since proponents of a MAR scheme do not know if a scheme will be approved or not (Page et al., 2020).

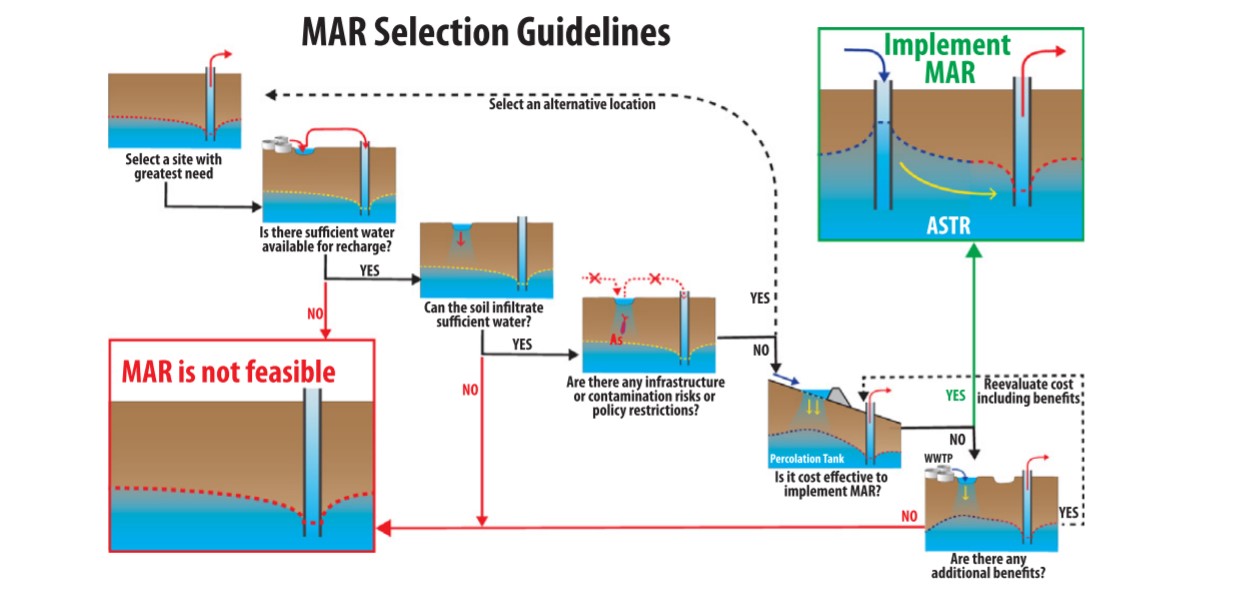

MAR Selection Guidelines

Source: Alam et al., 2021

Source: Alam et al., 2021

- In particular, the specific water supply needs of a site have to be understood.

- Priorities the objectives and be clear why you want to implement a MAR scheme: for instance, objectives are water security or restoration of a depleted aquifer.

- You have to understand if there is enough source water avaialble for the recharge. Which means you have to understand variability in the source water supply

- wastewater: is available all year around, stormwater is available in wet seasons.

- You also need maps or other information that help identify available and suitable aquifers.

-

Hydrogeological conditions and soil

-

You need policies or guidelines on MAR to protect health and environment.And you also have to see if there are basin water allocation plans.

- You have to consider the economic feasibility of a MAR project

- field investigations are necessaty and they make a quarter of the total capital costs

- but they are absolutely necessary to inform the design

Integrating MAR into nexus systems

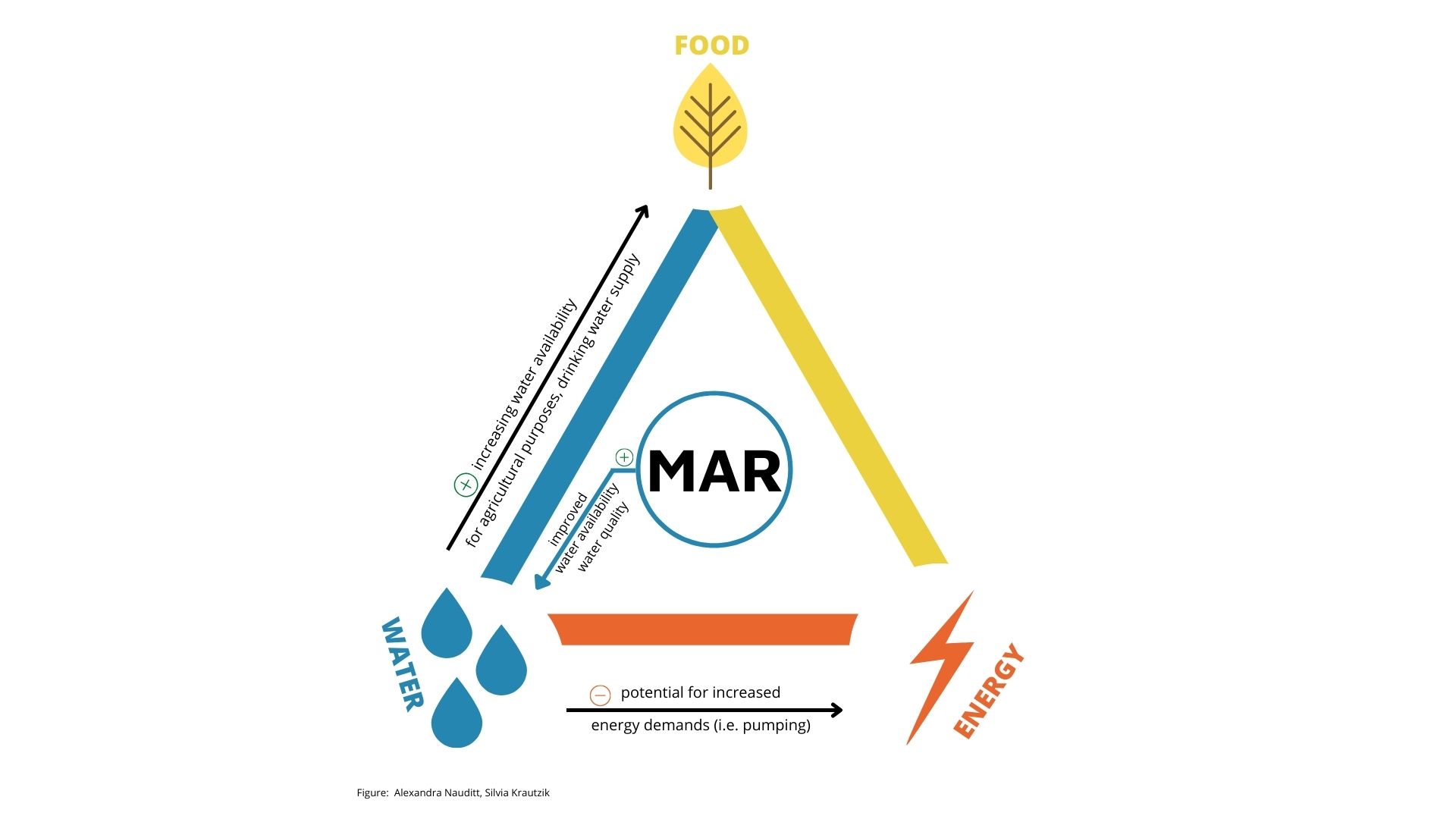

How does MAR interact with the different Nexus components?

Figure: Alexandra Nauditt, Silvia Krautzik

Figure: Alexandra Nauditt, Silvia Krautzik

Nexus related to MAR: In general, MAR can help storing water for the future. This can improve security of water supply for different uses such as domestic, industrial or agricultural consumption.

Looking at MAR from a nexus-perspective, there are several intersectoral relations and feedbacks to be considered: An increase in drinking water supply might benefit food security since there are many interconnections between water, nutrition, and human health. Water is not only used for drinking but it is also essential for a safe food preparation, including washing, boiling or steaming food. At the same time, MAR can increase water availability for agricultural purposes, securing irrigation for crops that are later eaten or further processed and sold.

Energy and greenhouse gas interconnections are important factors to consider when establishing a MAR scheme. Energy is used in different stages of MAR scheme planning, implementation and operation. For instance, construction techniques and required materials for a MAR scheme should be considered as well as the use of energy efficient pumps or using gravity flows instead of pumps are also a viable option. In general, renewable energy sources might be used on the MAR site to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC, 2009).

Potential Risks

The potential synergies and trade-offs also depend on specific MAR schemes as there are so many different techniques available. For instance, when implementing infiltration basin in an area, some additional trade offs might come from land requirements, potential clogging which is a key operational challenge where untreated or incompletely treated water is recharged or the mobilization of contaminants in the soil zone due to the recharge. Moreover, the infiltration basins might favor mosquito breeding that could impact human health over time (Maliva, 2019).

References

Alam, S., Borthakur, A., Ravi, S., Gebremichael, M., & Mohanty, S. K. (2021). Managed aquifer recharge implementation criteria to achieve water sustainability. Science of The Total Environment, 768, 144992. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.144992

AquaNes (2016): Demonstration site. Available at: http://aquanes.eu/Default.aspx?t=1673 (accessed 25/11/2021).

Bouwer, H. (2002): Artificial recharge of groundwater: hydrogeology and engineering. Hydrogeology Journal 10, 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-001-0182-4

Casanova J., Devau N., Pettenati M. (2016) Managed Aquifer Recharge: An Overview of Issues and Options. In: Jakeman A.J., Barreteau O., Hunt R.J., Rinaudo JD., Ross A. (eds) Integrated Groundwater Management. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23576-9_16

Dillon, P. Future management of aquifer recharge. Hydrogeol J 13, 313–316 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-004-0413-6

Dillon, P., Toze, S., Page, D., Vanderzalm, J., Bekele, E., Sidhu, J., & Rinck-Pfeiffer, S. (2010). Managed aquifer recharge: rediscovering nature as a leading edge technology. Water Science and Technology, 62(10), 2338–2345. doi:10.2166/wst.2010.444

Dillon, P., Stuyfzand, P., Grischek, T., Lluria, M., Pyne, R. D. G., Jain, R. C., Sapiano, M. (2018). Sixty years of global progress in managed aquifer recharge. Hydrogeology Journal. doi:10.1007/s10040-018-1841-z Page, D., Bekele, E., Vanderzalm, J., & Sidhu, J. (2018). Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) in Sustainable Urban Water Management. Water, 10(3), 239. doi:10.3390/w10030239

IGRAC (2018): MAR Portal. International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre. Available at: https://www.un-igrac.org/special-project/marportal

Liang, X., Zhan, H., & Zhang, Y.-K. (2018). Aquifer Recharge Using a Vadose Zone Infiltration Well. Water Resources Research. doi:10.1029/2018wr023409

NRMMC–EPHC–NHMRC (2009): Australian Guidelines for Water Recycling, Managing Health and Environmental Risks, Volume 2C—Managed Aquifer Recharge. Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council, Environment Protection and Heritage Council National Health and Medical Research Council. Available at: http://www.ephc.gov.au/ taxonomy/term/39 (accessed: 11/09/2021).

Maliva, R. G. (2019). Surface Spreading System—Infiltration Basins. SpringerBriefs in Electrical and Computer Engineering, 469–515. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11084-0_15

Page, D., Bekele, E., Vanderzalm, J., & Sidhu, J. (2018). Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) in Sustainable Urban Water Management. Water, 10(3), 239 https://doi.org/10.3390/w10030239

Salameh, E., Abdallat, G., & van der Valk, M. (2019). Planning Considerations of Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) Projects in Jordan. Water, 11(2), 182. doi:10.3390/w11020182

Sprenger, C.; Hartog, N.; Hernández, M.; Vilanova, M.; Grützmacher, G.; Scheibler, F.; Hannappel, S. (2017): Inventory of managed aquifer recharge sites in Europe: Historical development, current situation and perspectives. Hydrogeological Journal, 25, 1909-2345. doi: 10.1007/s10040-017-1554-8

Stefan C. & Ansems N. (2017): Web-based global inventory of managed aquifer recharge applications. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-017-0212-6